"They Fooled Us"

Seven months after the assassination of Haiti's president, the true masterminds remain unknown. But a failed "coup" plot that preceded it provides new information about those involved — and what the US and Haitian governments may have known ahead of time.

You can't kill the truth.You can't kill justice.

Even to many of those implicated in the assassination of Haiti's president and the attempted "coup" months earlier, nothing is as it seems. Meanwhile, the entire saga is connected to a still unsolved assassination 20 years earlier.

We may never know everyone responsible for the killing of Jovenel Moïse, but it is a legacy of foreign intervention and impunity that allowed it to happen in the first place.

Individuals arrested at Petit Bois. In the chair, with plastic hand ties is police inspector Marie Louise Gauthier.

Individuals arrested at Petit Bois. In the chair, with plastic hand ties is police inspector Marie Louise Gauthier.

Two individuals arrested at the Petit Bois apartment complex on February 7, 2021. On the right, agronomist Louis Buteau.

Two individuals arrested at the Petit Bois apartment complex on February 7, 2021. On the right, agronomist Louis Buteau.

Items seized at the Petit Bois apartment complex during the February 7, 2021 raid.

Items seized at the Petit Bois apartment complex during the February 7, 2021 raid.

Voice of America article from February 8, 2021 with Whitman's denial of involvement. Haitian state security released a video alleging Whitman was the ringleader of the Petit Bois plan. The article has since been removed from VOA's website.

Voice of America article from February 8, 2021 with Whitman's denial of involvement. Haitian state security released a video alleging Whitman was the ringleader of the Petit Bois plan. The article has since been removed from VOA's website.

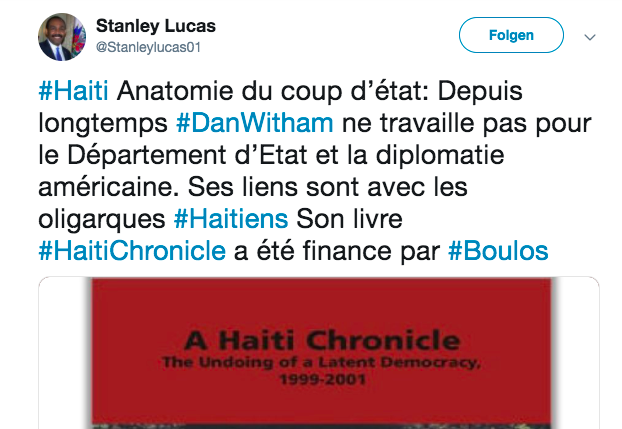

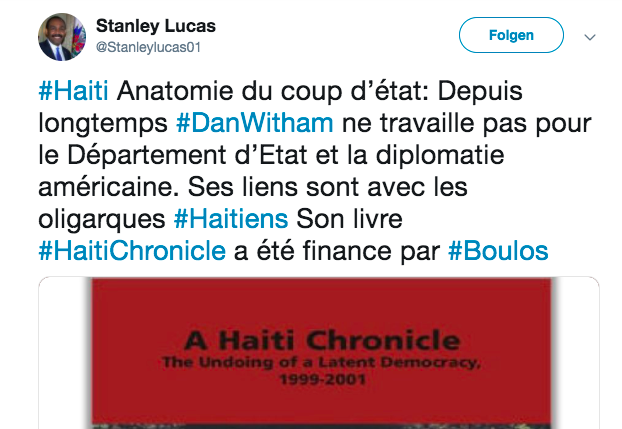

Since deleted tweet from Stanley Lucas, an advisor to president Jovenel Moise. Lucas previously worked for the US government funded International Republican Institute (IRI).

Since deleted tweet from Stanley Lucas, an advisor to president Jovenel Moise. Lucas previously worked for the US government funded International Republican Institute (IRI).

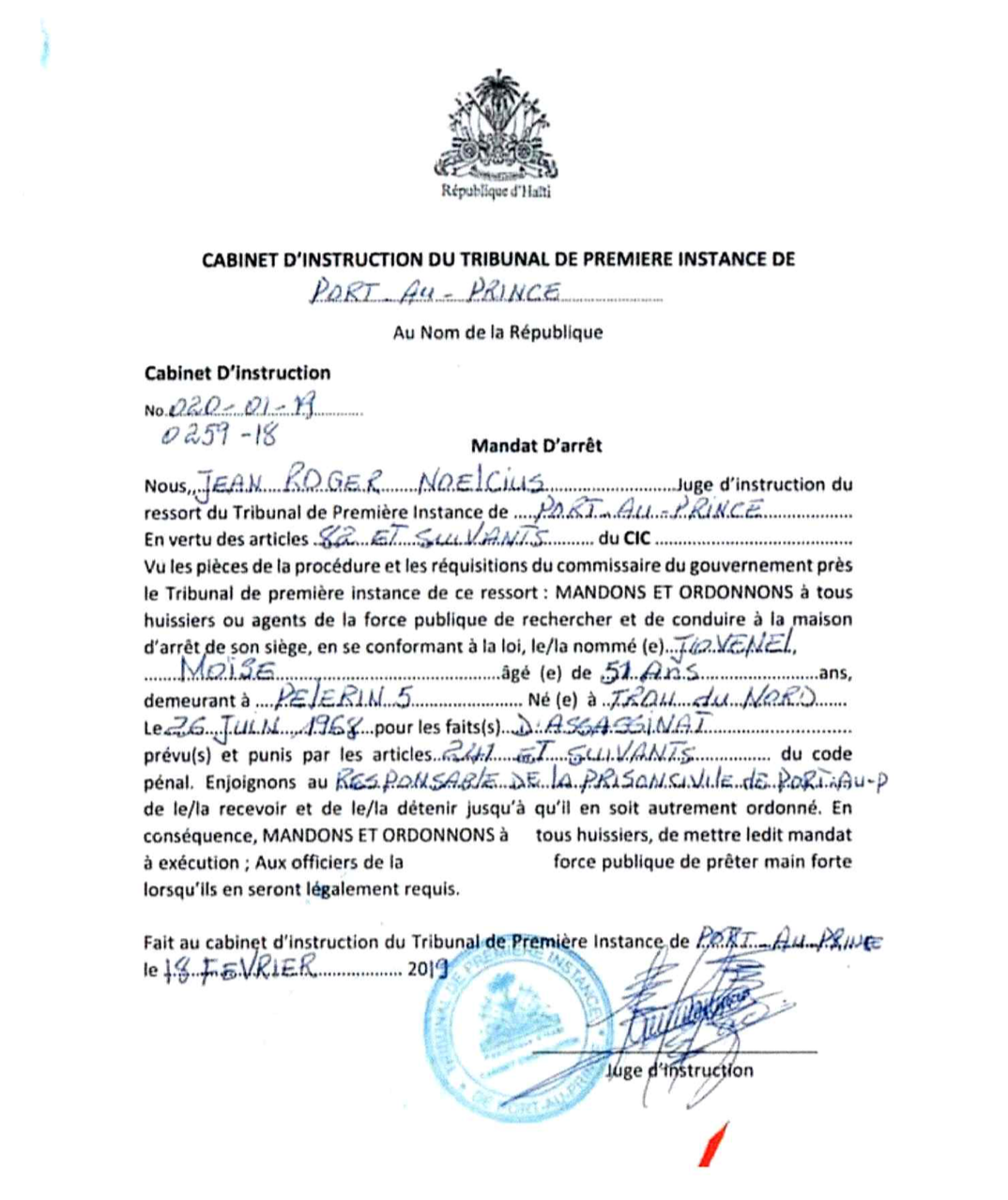

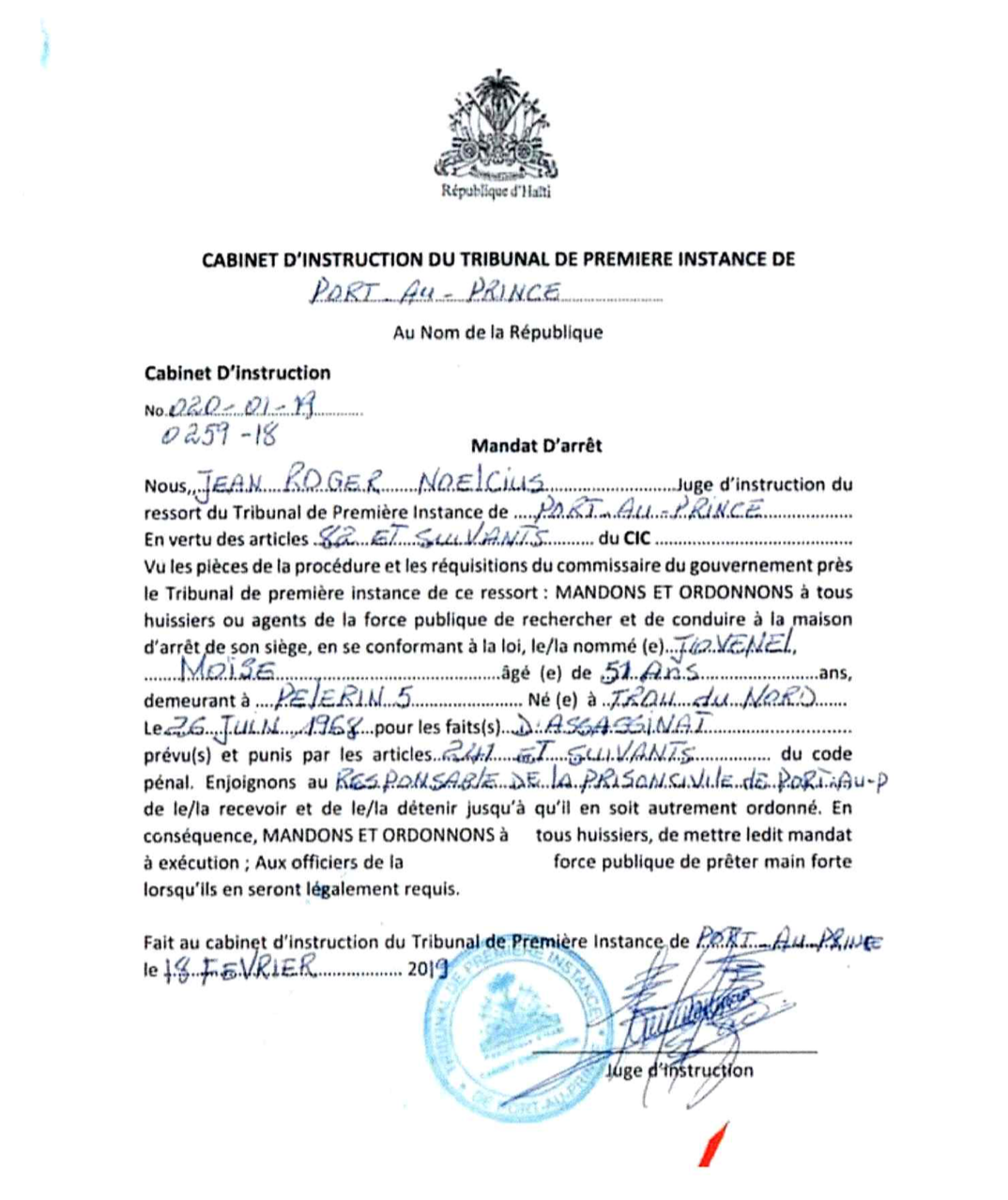

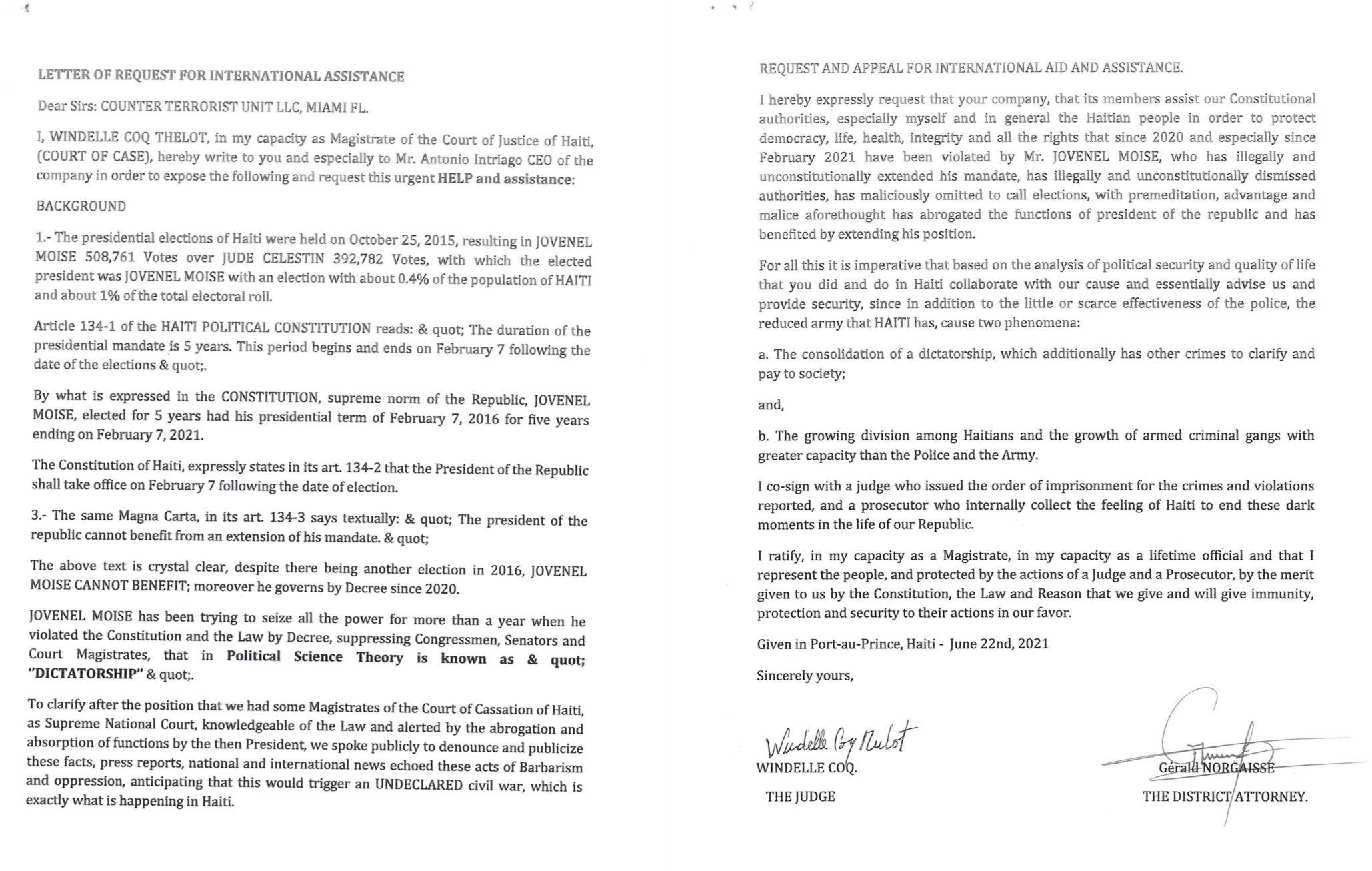

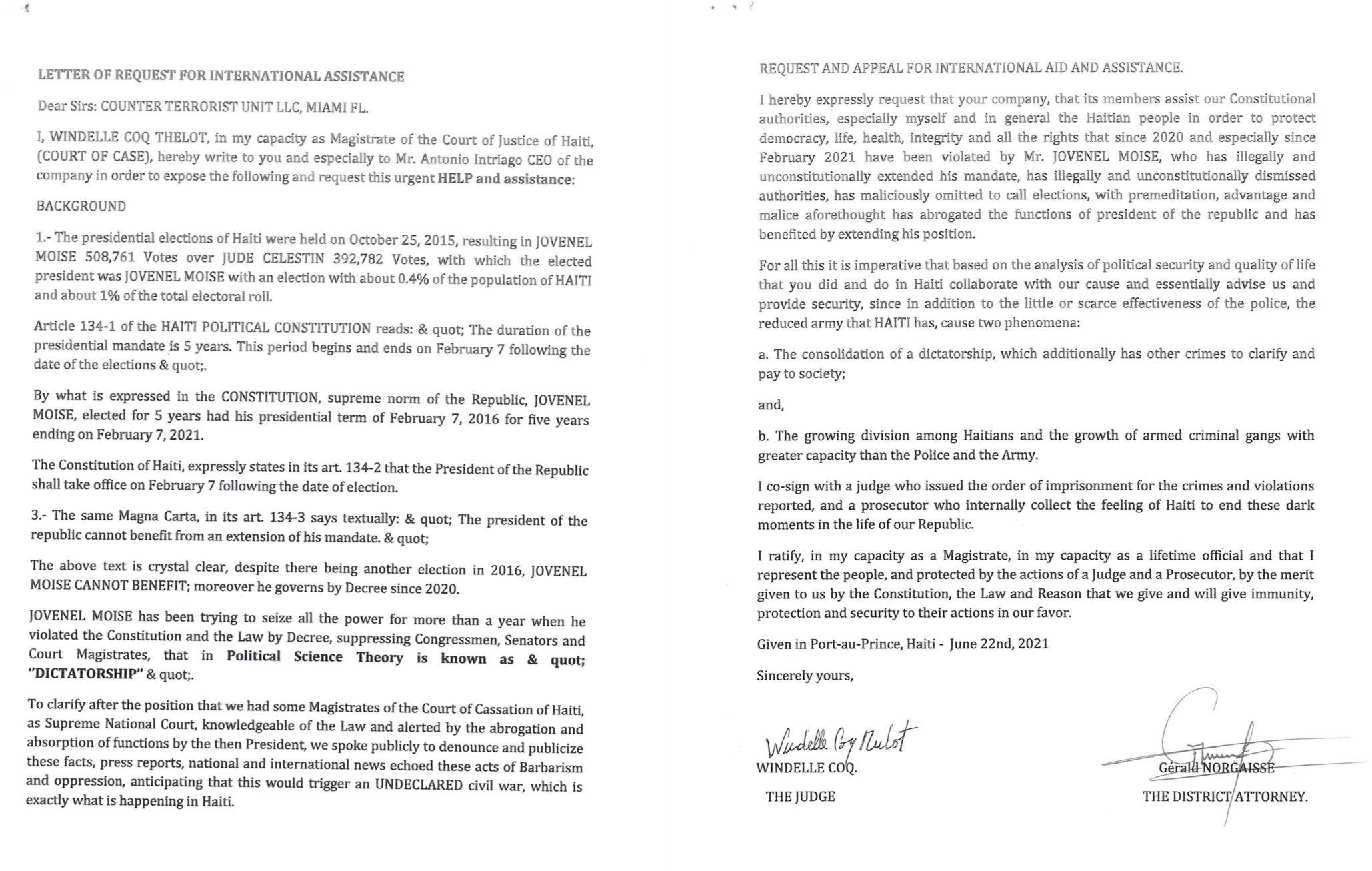

Copy of an apparent February 2019 arrest warrant for Jovenel Moise issued by Judge Jean Roger Noelciu, The document was provided to CTU Security, the Florida-based firm who contracted with at least some of the Colombian former soldiers implicated in the assassination. This is the same warrant, whose authenticity has not been confirmed, used as ostensible justification in the February 7, 2021 effort to replace Moise.

Copy of an apparent February 2019 arrest warrant for Jovenel Moise issued by Judge Jean Roger Noelciu, The document was provided to CTU Security, the Florida-based firm who contracted with at least some of the Colombian former soldiers implicated in the assassination. This is the same warrant, whose authenticity has not been confirmed, used as ostensible justification in the February 7, 2021 effort to replace Moise.

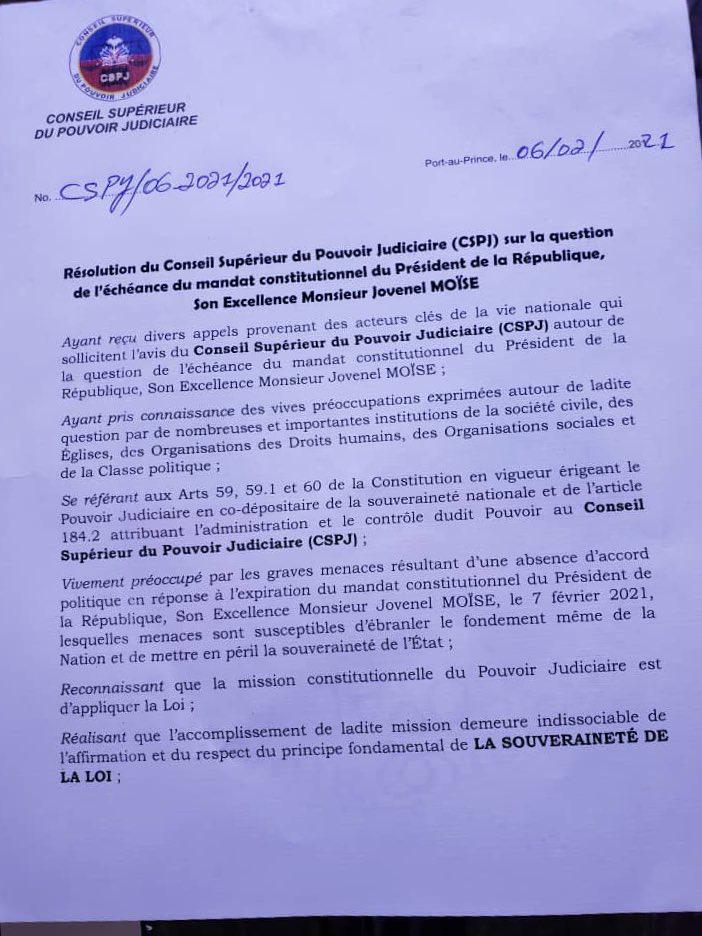

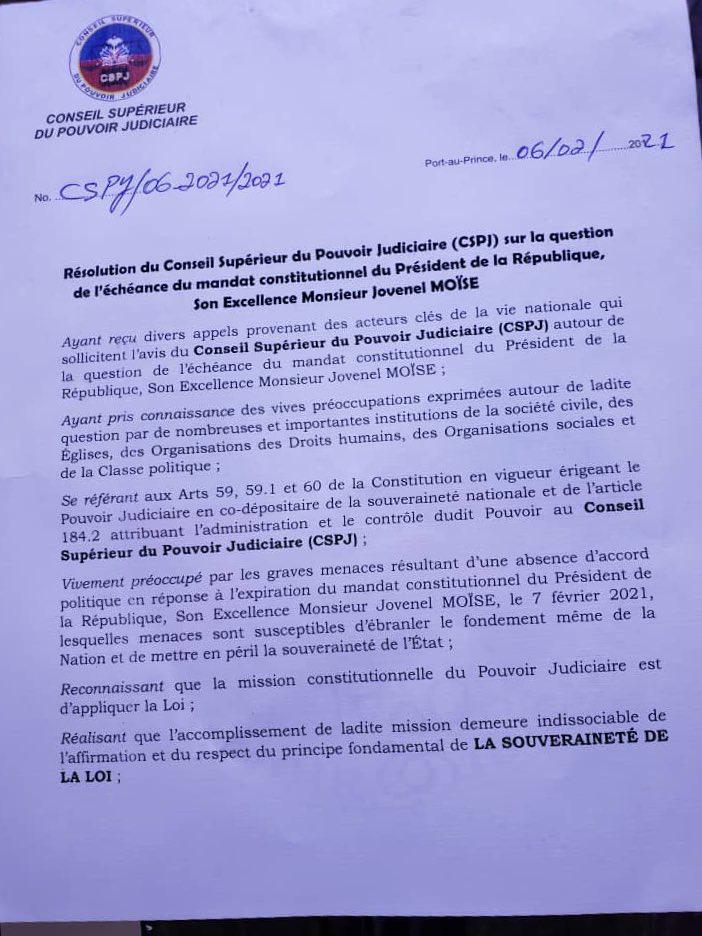

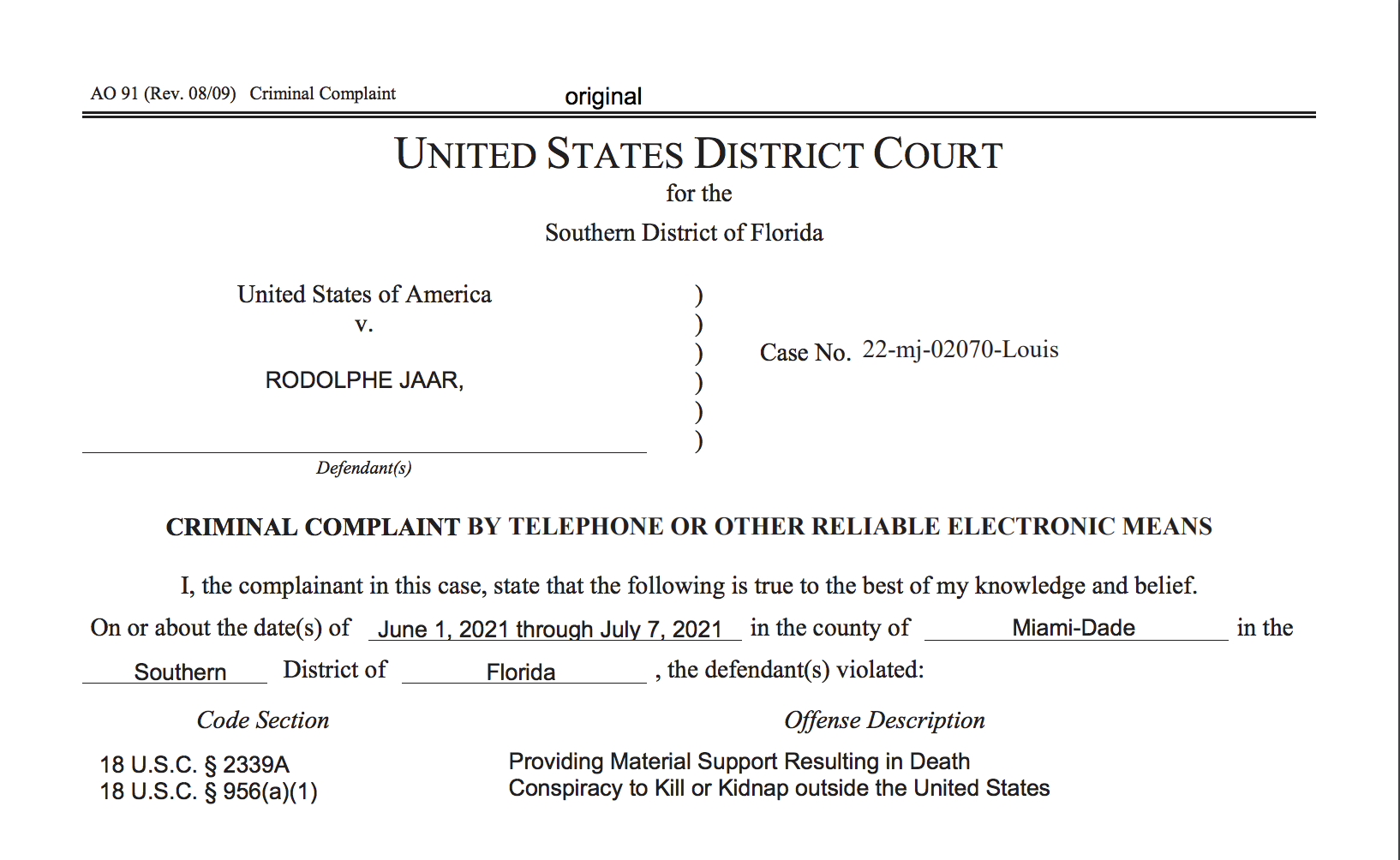

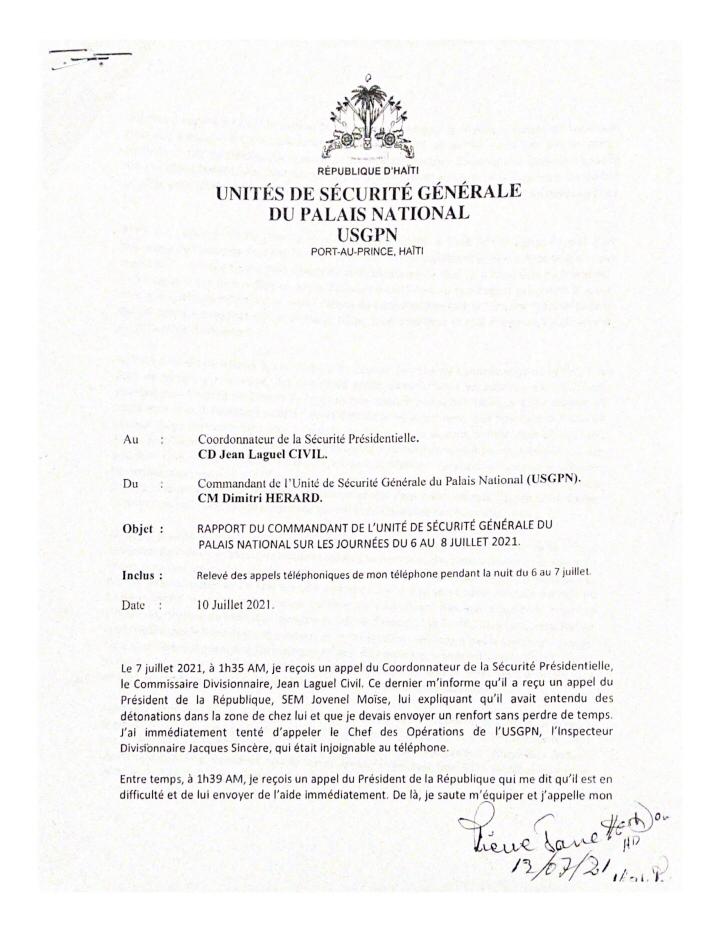

Resolution from Haiti's Superior Council of the Judiciary declaring that President Moise's mandate ended on February 7, 2021.

Resolution from Haiti's Superior Council of the Judiciary declaring that President Moise's mandate ended on February 7, 2021.

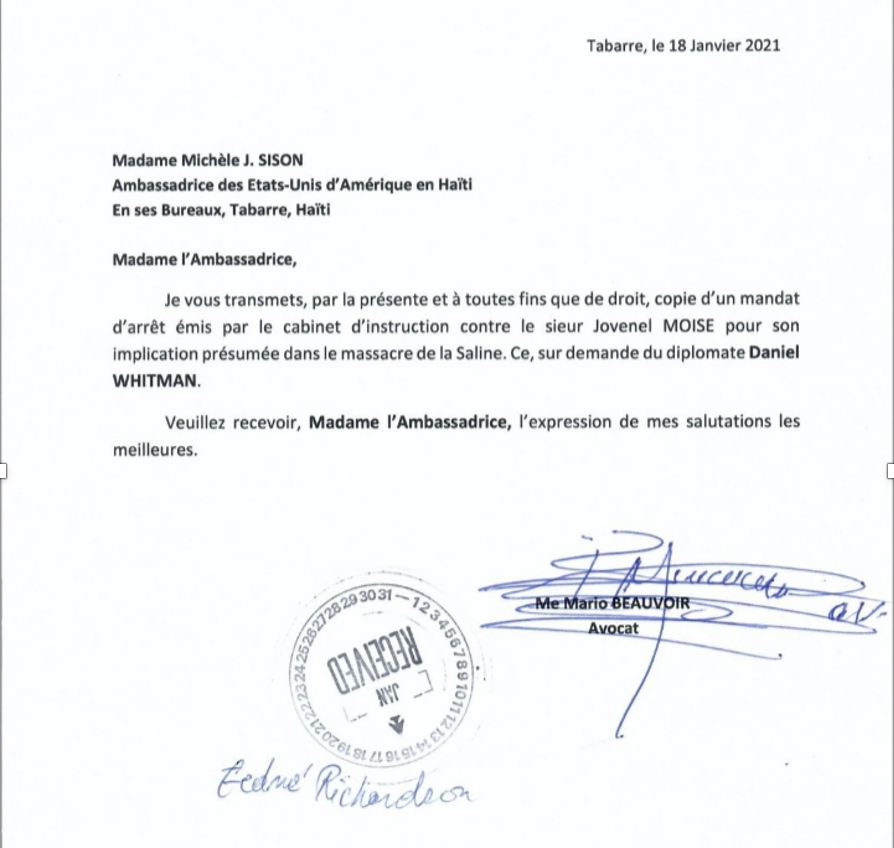

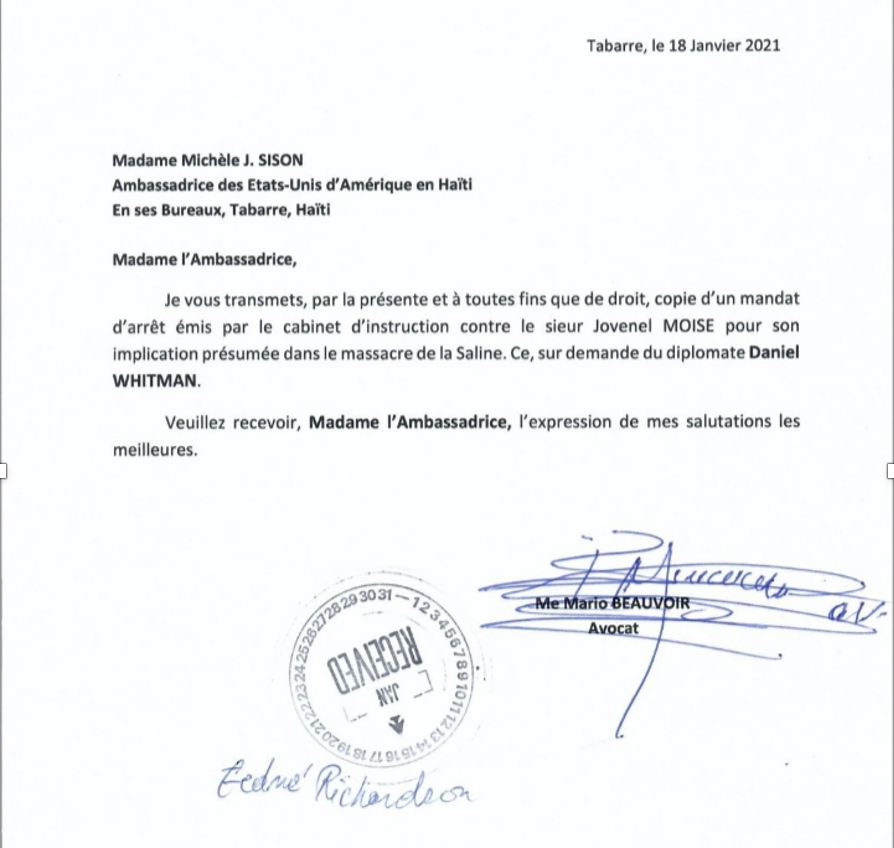

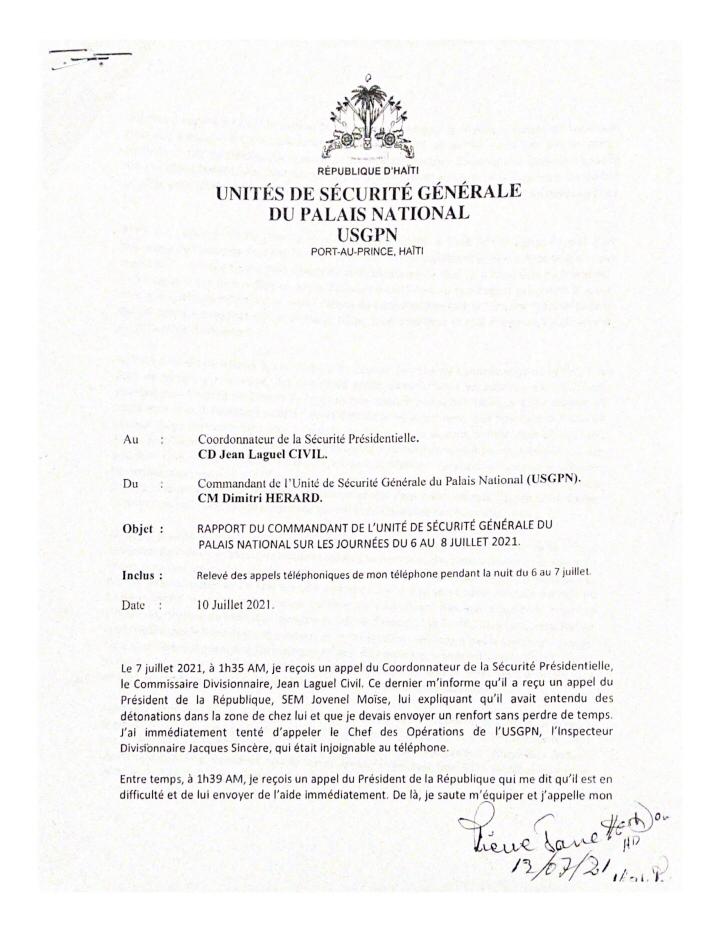

Letter from Mario Beauvoir to US Ambassador Michele Sison dated January 18, 2021 regarding an arrest warrant for President Jovenel Moise.

Letter from Mario Beauvoir to US Ambassador Michele Sison dated January 18, 2021 regarding an arrest warrant for President Jovenel Moise.

THE PETIT BOIS "COUP"

Individuals arrested at Petit Bois. In the chair, with plastic hand ties is police inspector Marie Louise Gauthier.

At 2:59 a.m. on February 7, 2021, Haitian police officers raided an apartment complex known as the Petit Bois residences in the Port-au-Prince’s Tabarre neighborhood. The buildings, a series of one-story, multicolored houses, sit just about one mile from the United States Embassy. By the time the sun had risen, photos of more than a dozen individuals lying or sitting on the pavement inside the compound were circulating on social media. Authorities had collected belongings, including a pile of crumpled Haitian bank notes, a condom, a handful of guns, and a rusted machete in the street. In one photo, a short man with disheveled salt-and-pepper hair, an oversized T-shirt, pajama pants, and socks with flip flops stares defiantly back at the camera. Altogether, 18 individuals were arrested, including a sitting Supreme Court judge, a high-level police inspector, and a former government minister, all accused of organizing a violent coup d’etat.

Two individuals arrested at the Petit Bois apartment complex on February 7, 2021. On the right, agronomist Louis Buteau.

“There was an attempt on my life,” President Jovenel Moïse told reporters a few hours later at an impromptu press conference from the tarmac at the Toussaint Louverture International Airport. He personally thanked the head of the Presidential Security Unit (USGPN), Dimitri Herard, for thwarting this nefarious plot. Moïse said the prime minister would provide more details and boarded a small, private jet, off to Jacmel, a coastal city in the South, for the opening of its annual carnival celebration. There, he and the first lady walked the streets showing no apparent fear for their lives.

The prime minister stated that some of those arrested “had contacted the official in charge of security for the national palace,” and had been planning on arresting the president and swearing in new leadership to oversee a transitional government. There was apparently an arrest warrant signed by a local judge. Soon thereafter, the government released audio recordings it claimed proved the seriousness of the matter. They were of conversations between Dimitri Herard, the man the president had just personally thanked for stopping the plot, and a few different individuals discussing plans to arrest the president.

Items seized at the Petit Bois apartment complex during the February 7, 2021 raid.

In one of the recordings, a female voice tells Herard, “Listen, I received an order from the State Department.”

“Yes, they contacted me too,” Herard responds.

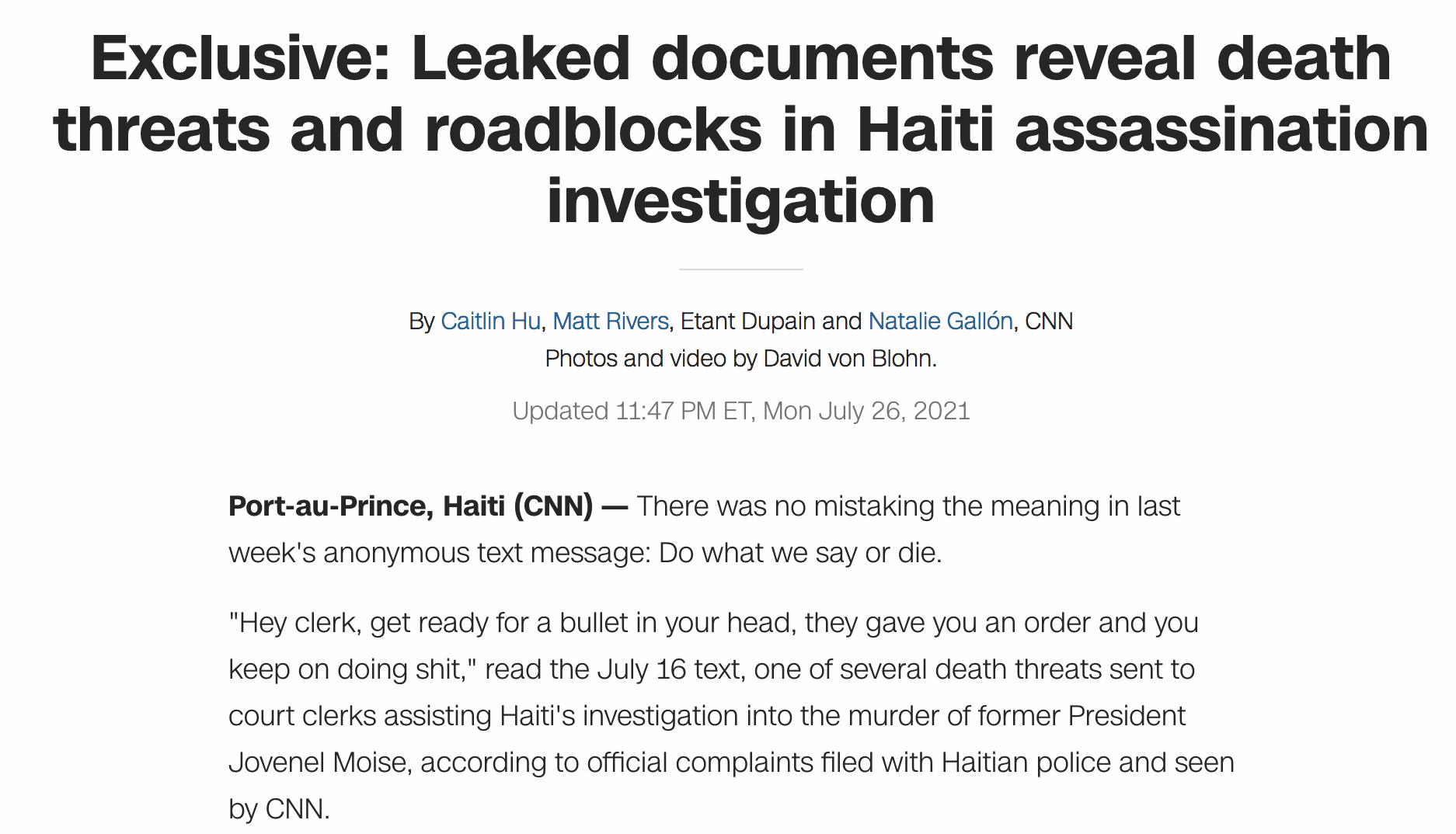

The alleged State Department officer was quickly identified as Daniel Whitman, a retired member of the US foreign service, who had briefly served in Haiti in the early 2000s. Whitman has denied any involvement in the plot. In fact, I would later learn that someone in Haiti had been impersonating Whitman. Various political leaders, journalists, and members of civil society said they had also been contacted by someone claiming to be Whitman. The narrative made little sense. Who had impersonated Whitman, and why? And, if what the authorities said was true, it seemed the entire plot rested on the involvement of the president’s chief of security, Herard, whom the president was hailing as a hero. Was it all a ruse? A set-up to entrap the government’s opponents?

Voice of America article from February 8, 2021 with Whitman's denial of involvement. Haitian state security released a video alleging Whitman was the ringleader of the Petit Bois plan. The article has since been removed from VOA's website.

Since deleted tweet from Stanley Lucas, an advisor to president Jovenel Moise. Lucas previously worked for the US government funded International Republican Institute (IRI).

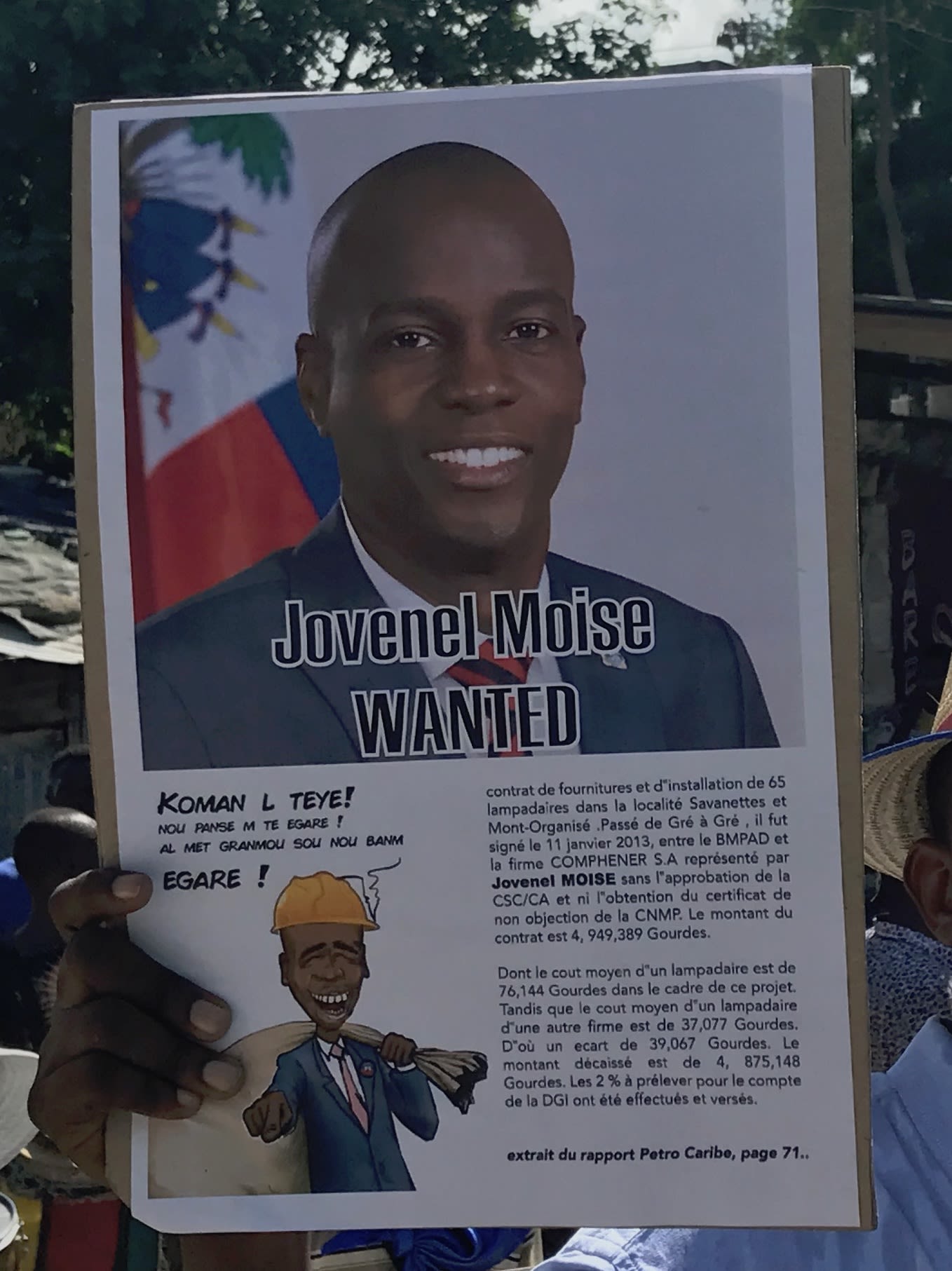

February 7 was not just the beginning of carnival; it was also the day that Haitian constitutionalists, opposition politicians, and civil society organizations argued that President Moïse’s term officially ended. For them, the only coup was Moïse staying in office. His inauguration had been delayed by a year over a contested electoral process, and, the argument went, the president had lost that year of his mandate. Protests calling for his resignation and the formation of a transitional government had been building for years. Political organizations had been meeting openly for many months debating and discussing plans for a post-Moïse political future. Moïse, however, with the strong backing of the Organization of American States (OAS), United Nations, and US State Department, argued that he should remain in office for another year, until February 7, 2022.

Copy of an apparent February 2019 arrest warrant for Jovenel Moise issued by Judge Jean Roger Noelciu, The document was provided to CTU Security, the Florida-based firm who contracted with at least some of the Colombian former soldiers implicated in the assassination. This is the same warrant, whose authenticity has not been confirmed, used as ostensible justification in the February 7, 2021 effort to replace Moise.

Exactly five months after the arrests at Petit Bois, in the early morning hours of July 7, Jovenel Moïse was assassinated, shot at least a dozen times in his home in the hills above Port-au-Prince. None of the two dozen or so security guards ostensibly protecting the president were injured, raising questions over their involvement in an apparent plot. Herard, hailed as thwarting the February plot, is now in jail. So far, more than 40 suspects in the assassination have been arrested, including 18 retired members of the Colombian military and more than a dozen Haitian police officers. Arrest warrants have been issued for many more individuals, including another Supreme Court judge.

Resolution from Haiti's Superior Council of the Judiciary declaring that President Moise's mandate ended on February 7, 2021.

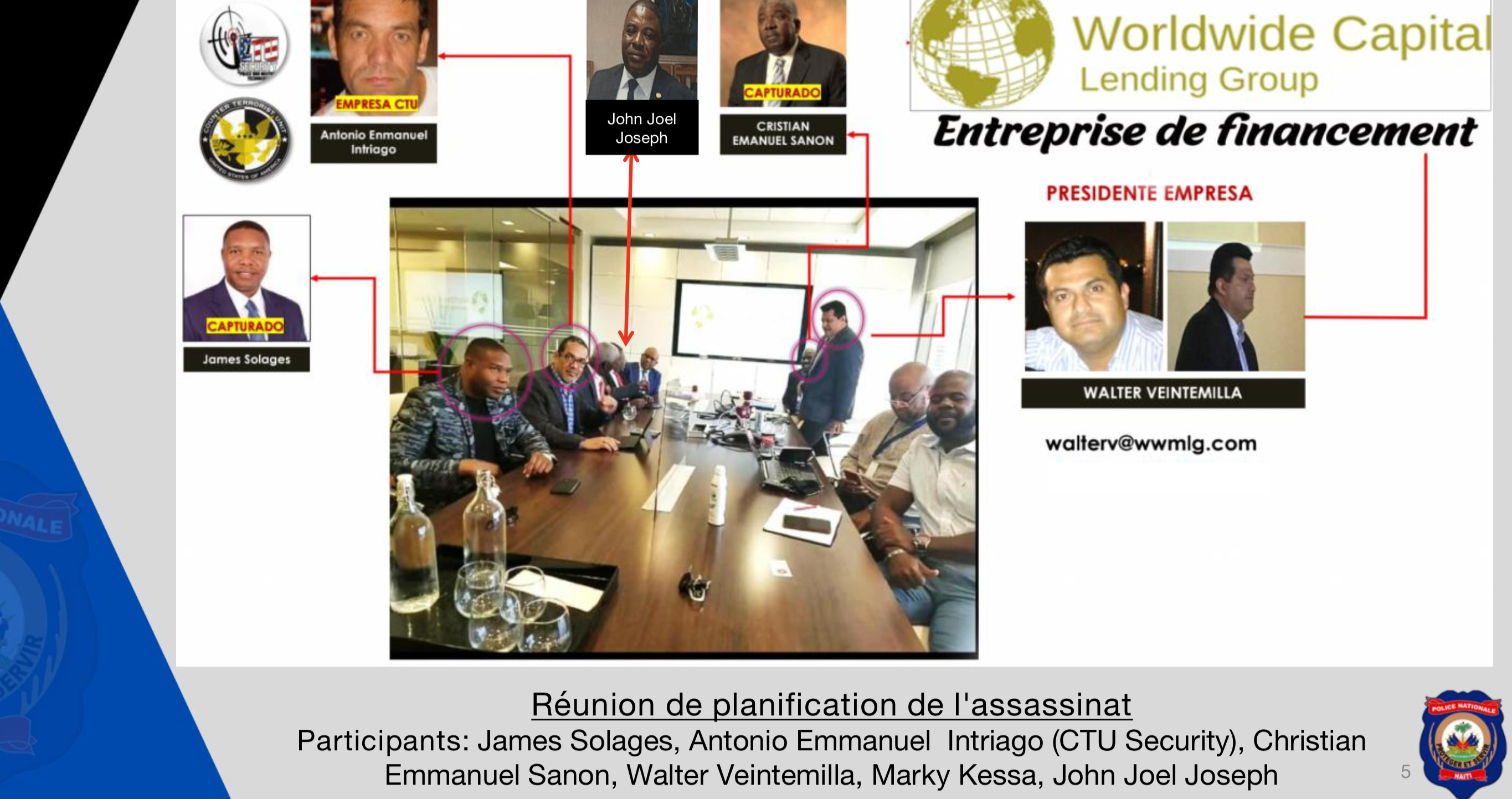

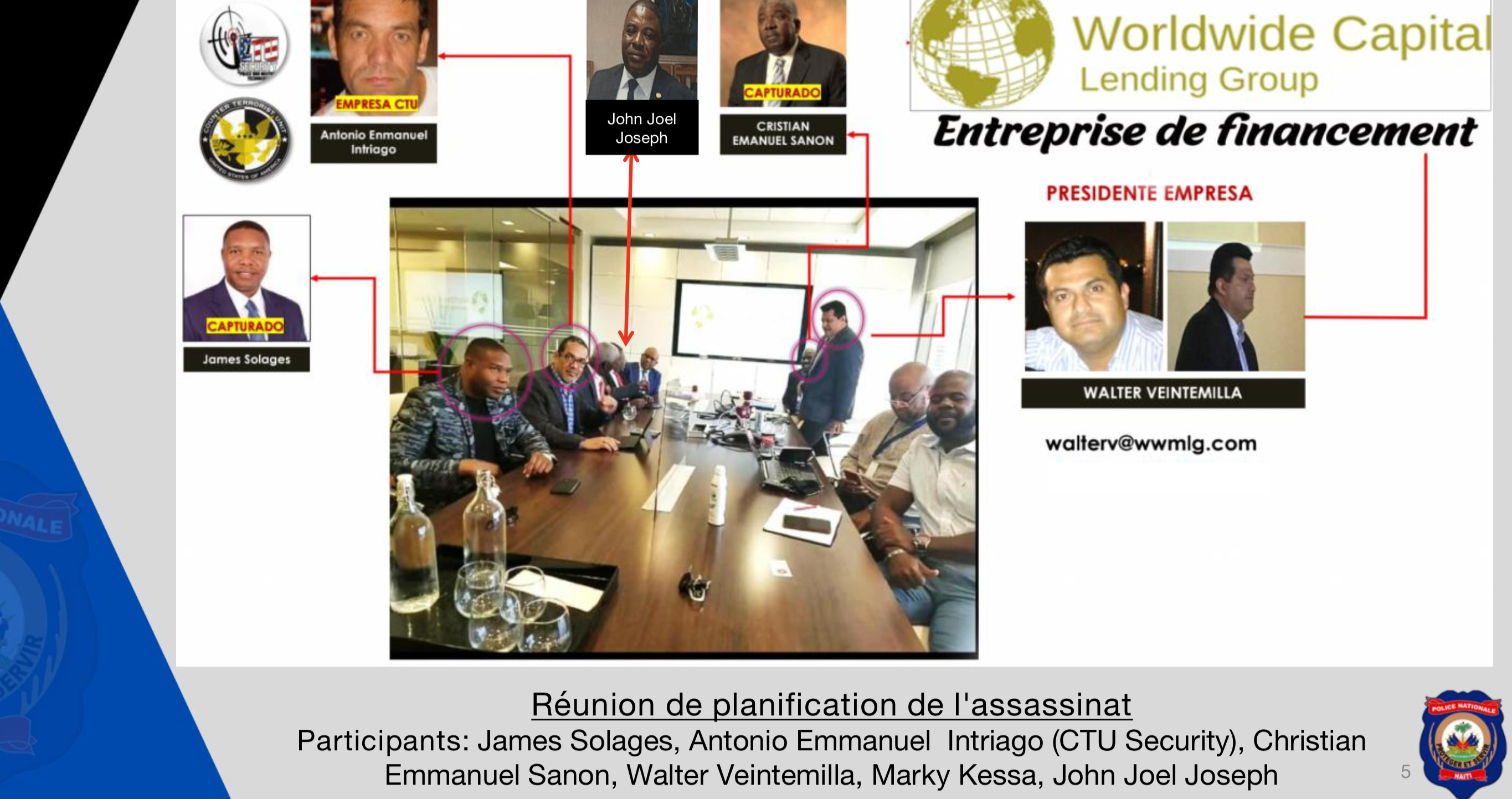

Few believe the official investigation, conducted with the support of the FBI, Interpol, and governments throughout the region, has identified the assassination's true masterminds. Nevertheless, police named a Haitian-American pastor, Dr. Christian Emmanuel Sanon, as the ostensible ringleader. Like those arrested five months earlier, Sanon allegedly had a plan to detain the president and lead a transitional government. Police found a crumpled-up arrest warrant in a home used by some of the suspects; it was the same warrant that had been used in Petit Bois. And, in another parallel to the February events, multiple suspects in the assassination have claimed that various US agencies were aware of or directly supported their actions. In a highly unusual statement, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) even acknowledged that at least one of those arrested in connection with the assassination had worked for the agency as a confidential informant.

Letter from Mario Beauvoir to US Ambassador Michele Sison dated January 18, 2021 regarding an arrest warrant for President Jovenel Moise.

There remain more questions than answers regarding the president’s shocking death. But, to begin to understand what transpired at the president’s residence that night in early July, one must begin five months earlier, with the predawn raid at the Petit Bois apartment complex.

The following investigation, based on dozens of interviews, including with Sanon and many of those arrested in February, as well as exclusively obtained communication records and internal investigative files, reveals new details about the February coup attempt and its connection with the president’s assassination. This is a story of deceit, of high-level political machinations, of foreign interference, and of the cumulative impact of decades of impunity. It sheds new light on key actors involved behind the scenes in both cases, including individuals now wanted in connection with the president’s killing.

For the first time, the identity of the individual impersonating former State Department official Daniel Whitman, the person believed to be a key instigator of the February plot, is revealed. Taken together, the findings raise new questions about what authorities, both in Haiti and abroad, knew ahead of the July assassination. There was little secret about the meetings taking place at Petit Bois, or about Sanon’s desire to lead a transitional government.

Yet one led to illegal mass arrests, and the other resulted in the president’s brutal assassination. Why? And could it have been stopped?

MASTERMIND OR CON ARTIST?

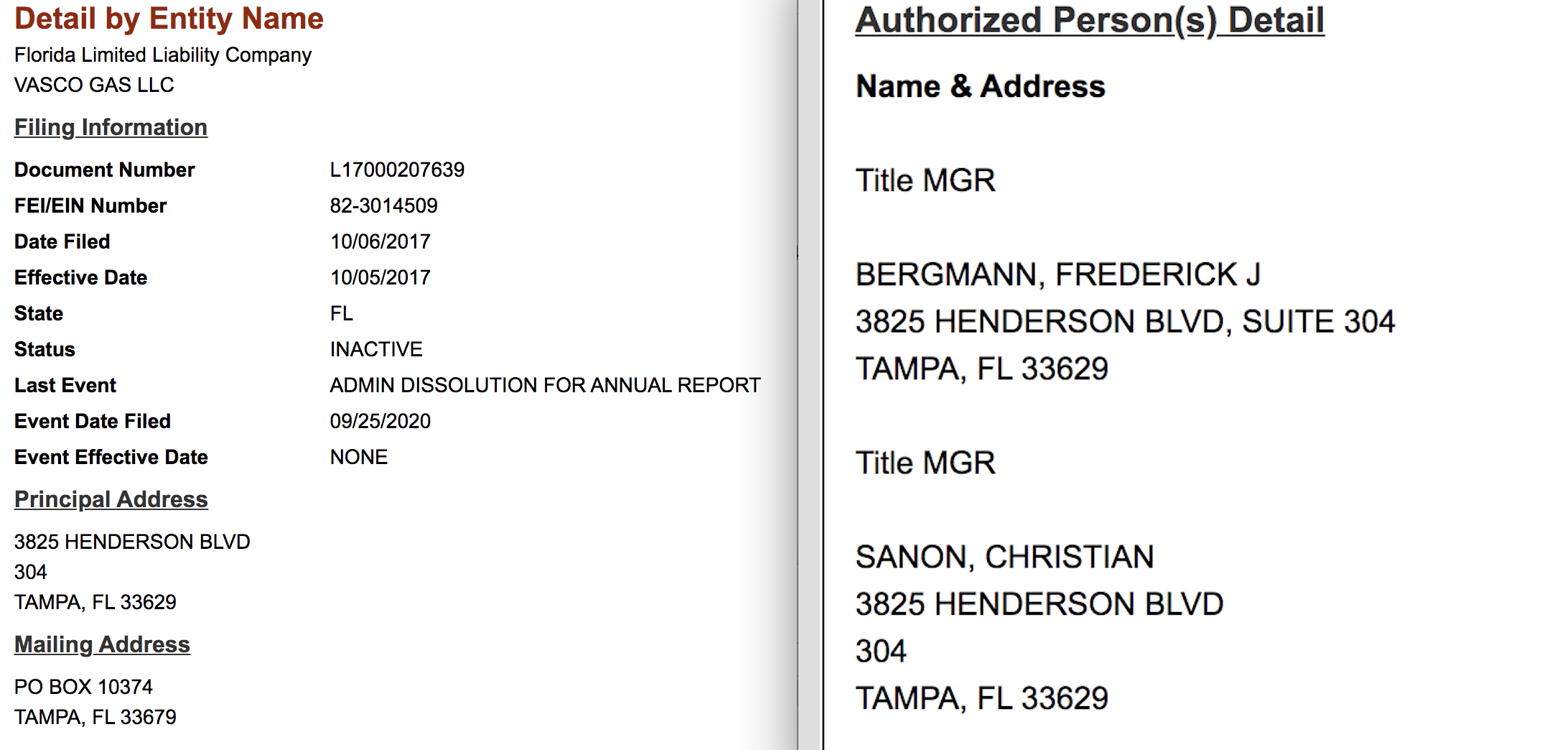

Christian Emmanuel Sanon, 63 years old, is a tall, burly, and personable man. He’s a talker. It’s a skill he’s used for decades, as a pastor in Florida and as a businessman both in the United States and in Haiti. But that talk hasn’t led to much in the way of commercial success. Florida corporate records show a slew of companies, most now inactive, registered in Sanon’s name. In 2013, he filed for bankruptcy. And there is no shortage of individuals who, over the course of many years, felt like they had been ripped off by Sanon. As one source who had known him for years put it, “he’s the type of guy who tells you he’s got a great deal for you, but, when you show up, it turns out he is just looking for more money.”

Screenshot from a 2011 video from Christian Sanon titled "Dr. Christian Sanon on Corruption in Politics." Sanon's presidential ambitions date to at least 2010, after the devastating earthquake struck Haiti.

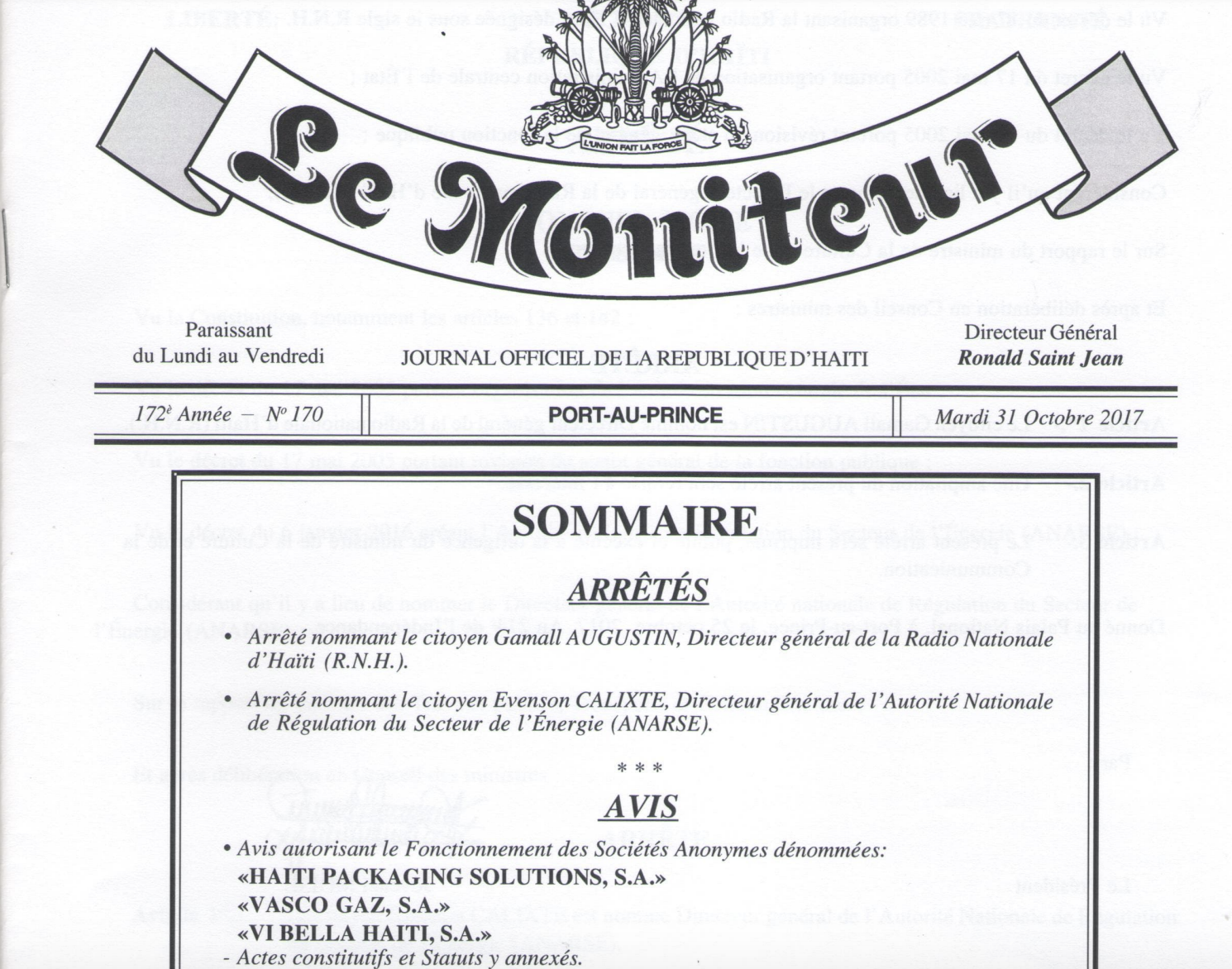

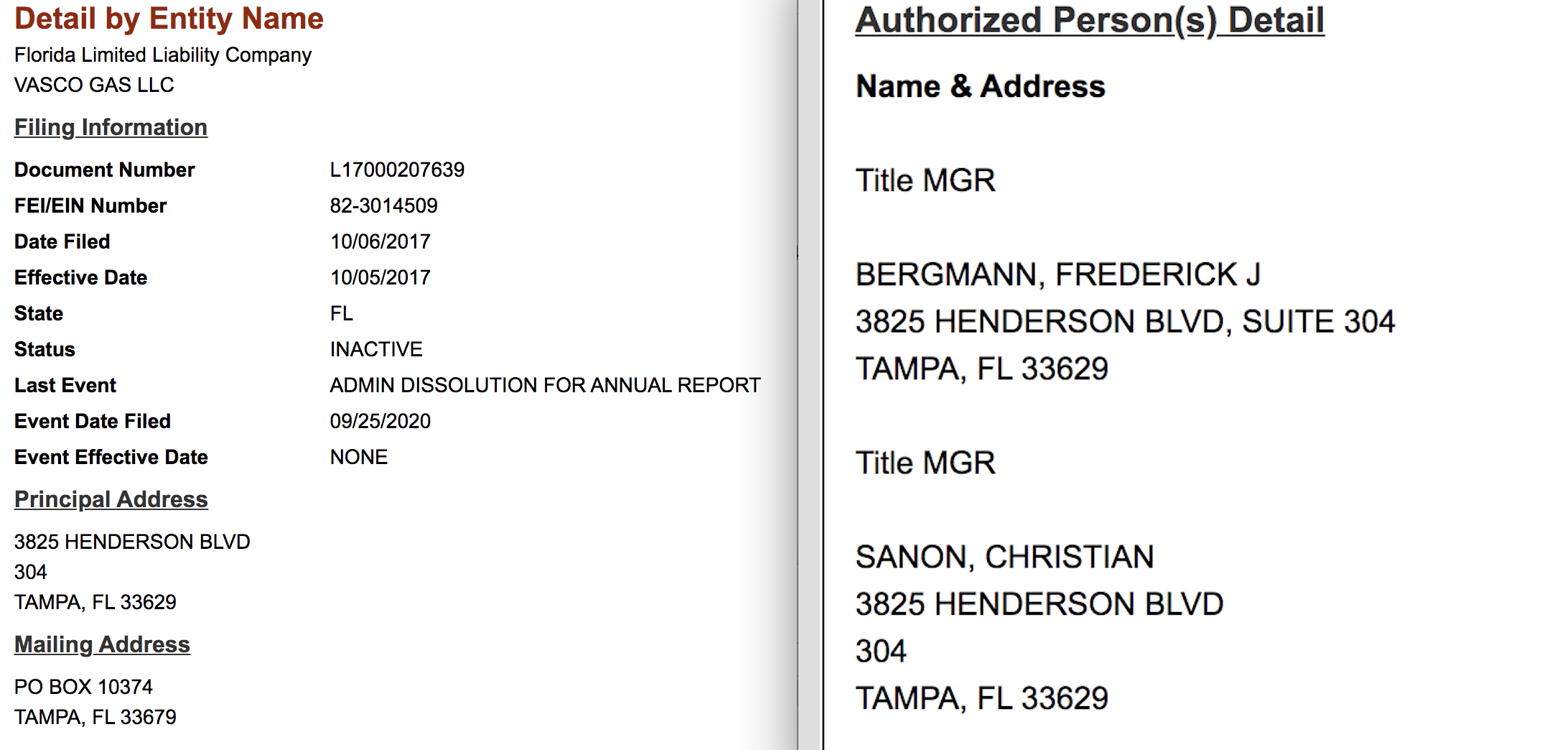

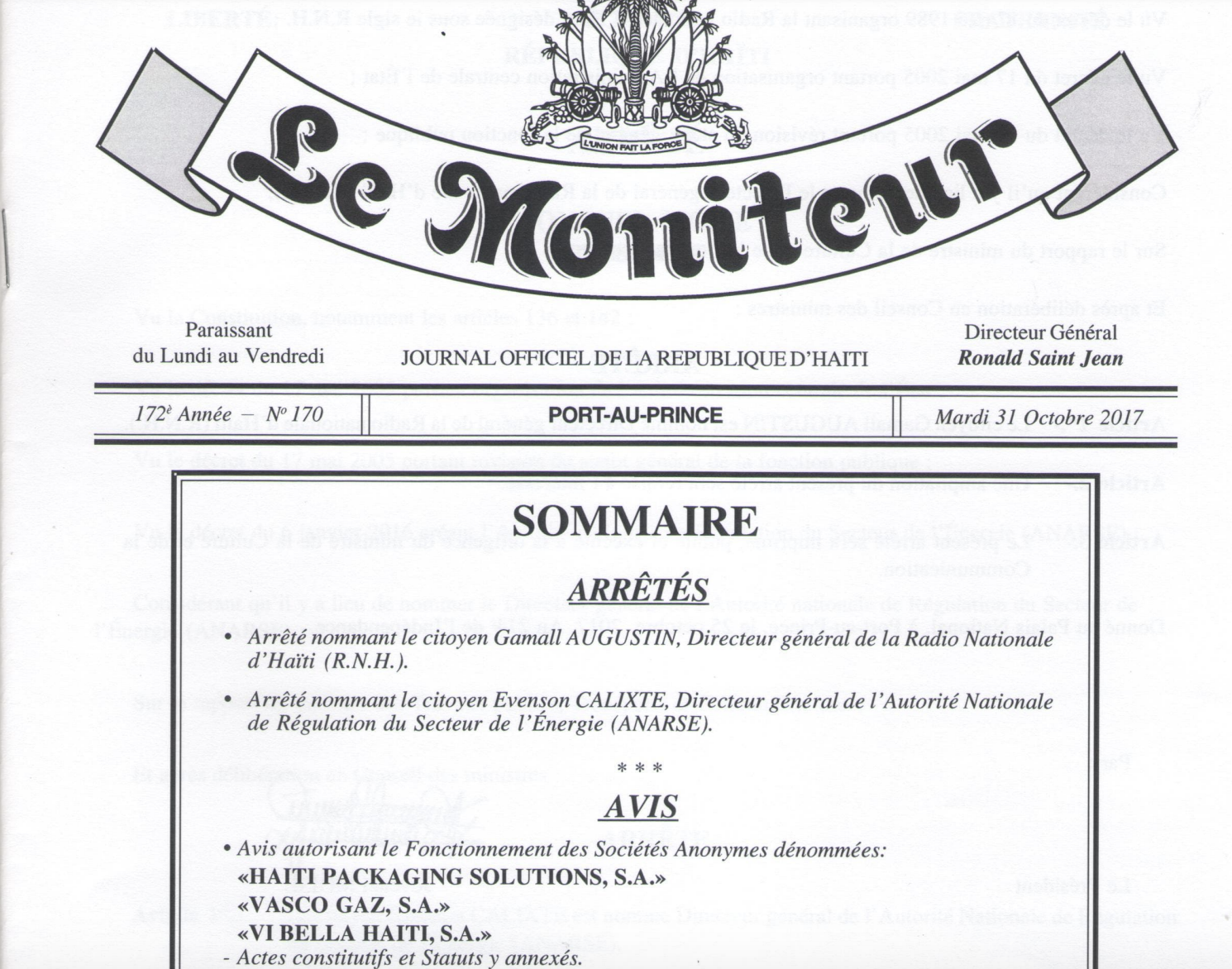

In October 2017, Sanon created a new company in Haiti, Vasco Gaz. The same month, he showed up on the incorporation paperwork for a Tampa Bay-based company with the same name. Though he had no real experience in the industry, the company found some initial success in Haiti. Within months of its creation, the Haitian government had awarded Vasco multiple tenders to deliver kerosene, diesel, and gas. Other players in the industry were suspicious. How could this newcomer underbid them all and actually deliver?

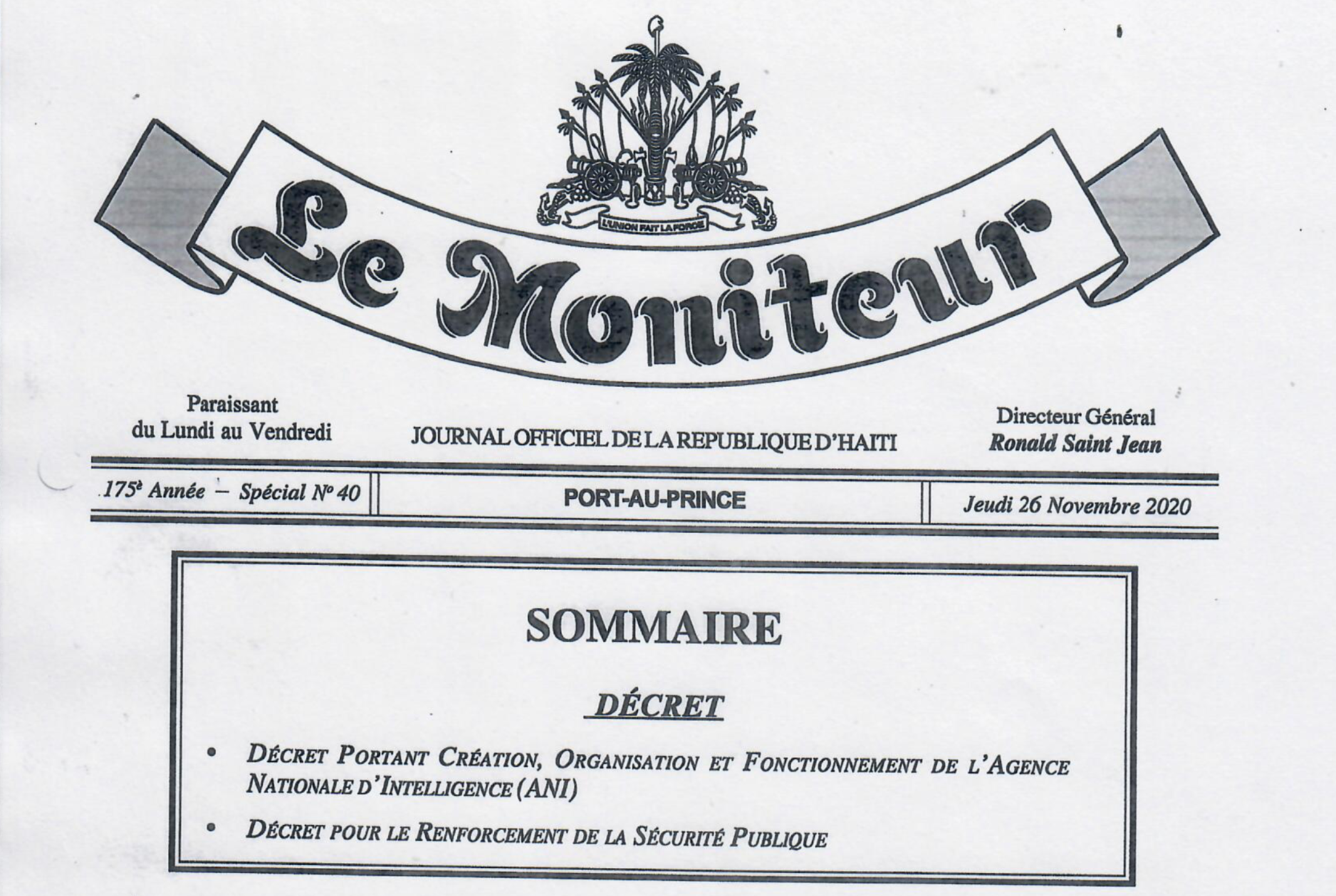

Notice in the official government publication Le Moniteur concerning the creation of a new company, Vasco Gaz S.A. Dated October 31, 2017.

The answer was that it couldn’t. Vasco Gaz reportedly never delivered on its promises, and throughout 2018, Haiti experienced a number of fuel shortages partially as a result. Eventually, the government agency responsible for importing fuel blacklisted the company and turned to other suppliers. Another Sanon business venture had failed, but the fact that he got the contract at all indicates he had some influential connections. Not long after, Sanon turned to his most ambitious scheme yet: organizing a team to lead a transitional government in Haiti.

Florida business registration of Vasco Gas LLC with Christian Sanon listed as manager. From sunbiz.org.

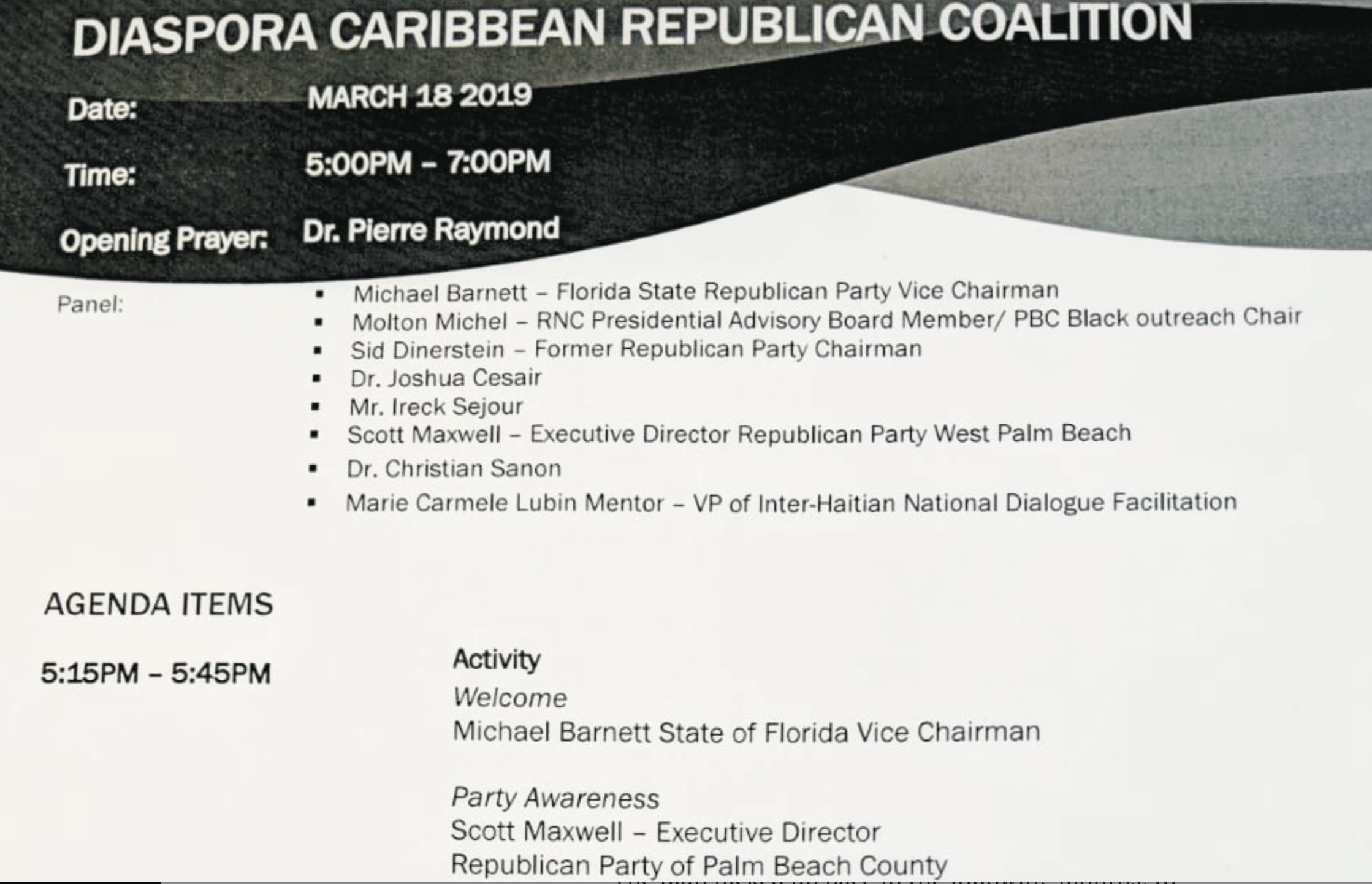

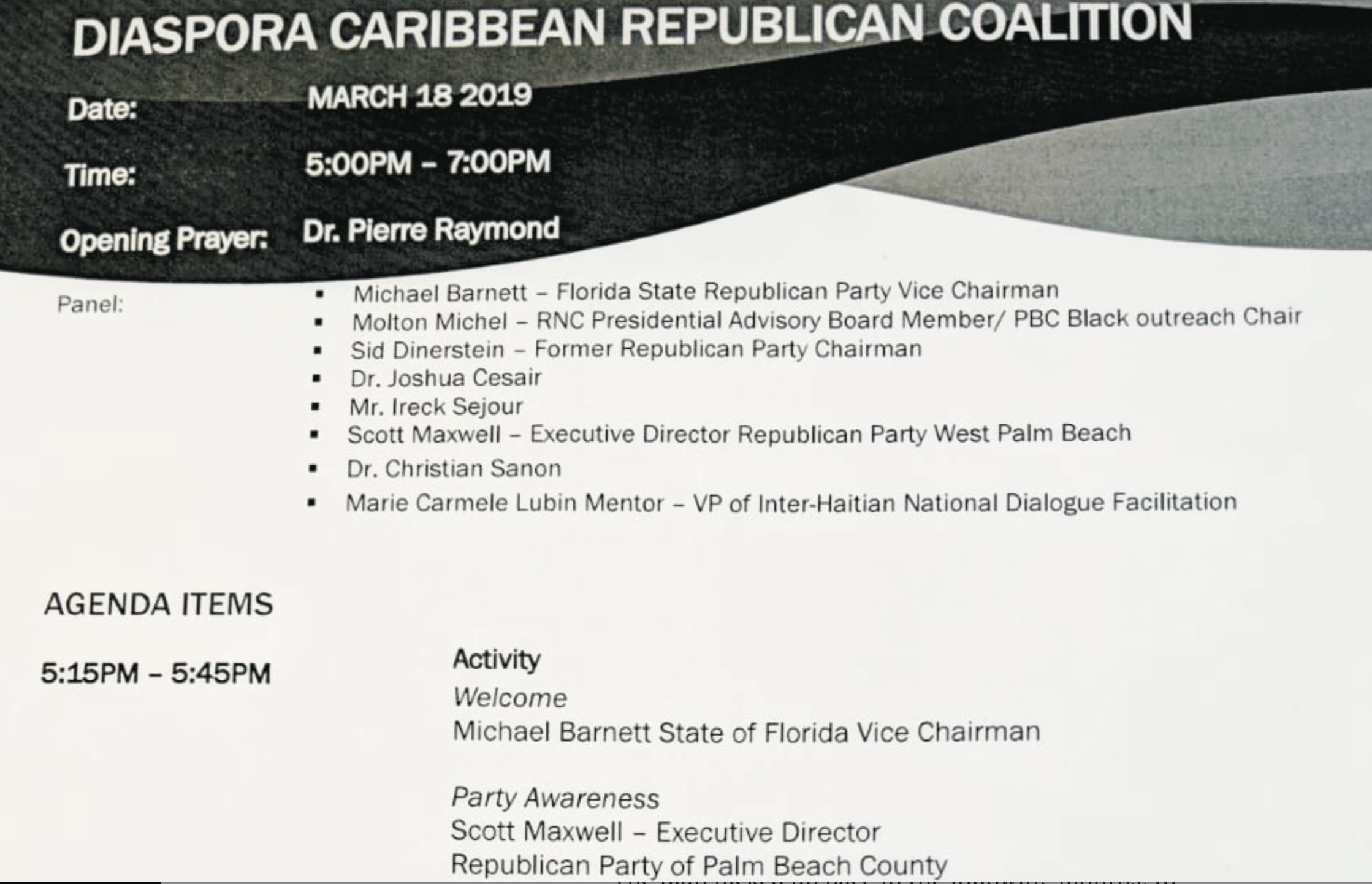

In early 2019, Sanon spoke at a South Florida gathering organized by the Diaspora Caribbean Republican Coalition. The event was attended by a number of local Republican officials, including the vice chairman of the Florida State Republican Party. After the event, Sanon met with a handful of attendees and explained that he was putting together a group of individuals and coming up with a plan to lead a transitional government in Haiti. He claimed to have close connections with the Trump administration and with the US State Department.

Flyer from a March 18, 2019 meeting of the Diaspora Caribbean Republican Coalition listing Christian Sanon as a panelist.

The plan picked up pace in the following months. In June, Sanon claimed to have had a meeting with the US Embassy in Port-au-Prince. At the time, a source who had been in contact with Sanon sent me a two-page document outlining the initial transition plan, which included disbanding parliament, transferring executive power to the Supreme Court, and naming a new prime minister. Sanon even claimed to have personally met Donald Trump at Mar-a-Lago, though there is no evidence this actually took place. There was little reason to believe the Trump administration had any interest in ousting Moïse, who had been a reliable ally in the US effort to overthrow Nicolas Maduro in Venezuela, the administration’s main agenda in the region. Sanon may never have met Trump at Mar-a-Lago, but in early 2019, Moïse had.

In late September 2019, I received a call from Sanon. He explained that he had been working with a team of individuals with the goal of finally putting Haiti on the right track. “Right now, the president has lost the trust of the people,” he explained. Protests had been building for more than a year. “The people will listen to another voice,” he continued.

He explained that, in the absence of the president, the constitution called for a leader from the Supreme Court to assume the presidency. The group he had been working with initially believed that judge to be Wendelle Coq Thélot, but, he told me, the United States had said no to her, apparently due to allegations of corruption. So now, he added, they were in discussions with other judges to find a replacement.

“We’re putting a group together and getting ready for if there is US support,” he said. And, I asked, what sort of connections did he have with the US government? “We are trying to make connections with people that can help us,” he vaguely explained, before adding that he had access to individuals in both the State Department and White House. Sanon assured me that Moïse would be willing to resign. “The president is just waiting for someone to tell him to go,” he said.

I mostly discarded my brief conversation with Sanon. Over many years following events in Haiti, I’ve realized there are lots of stories and plenty of individuals with wild sounding plans and even wilder claims of US connections. After decades of US political intervention and subterfuge, the perception is that US support is politically deterministic. If one wants to build support for their political project, whatever that may be, convincing others that the US supports it becomes almost a necessity.

In any case, it was no surprise that people, both in Haiti and the diaspora, were organizing around potential transition plans. It was happening in the open, and Sanon’s seemed far from the most serious. A few months later, a large grouping of political organizations and civil society groups met at the Marriott Hotel in Port-au-Prince to publicly discuss plans for a transitional government. Most honestly seemed to believe that the Moïse administration would fall at any moment. It made sense to plan for what would come next. Politicians close to the government, however, alleged the Marriott meetings and other discussions over a transitional government were “plot[s] against the internal security of the state.”

On July 10, 2021, three days after Moïse's assassination, I received a message from an old contact of Sanon, alerting me that the pastor had been arrested in Haiti. The next day, the chief of the Haitian police held a press conference and announced to the world that Christian Emmanuel Sanon had masterminded the assassination of the president. It had been nearly two years since Sanon had told me of his plans to lead a transitional government in Haiti. I had heard stories of his failed business ventures, scams, and other seemingly harebrained plots. I was immediately skeptical that Sanon could have been the puppet master pulling the strings behind such a high-profile crime.

Slide from a presentation made by the Haitian National Police claiming this was the meeting where the assassination was planned. The police said the meeting took place in the Dominican Republic. In fact, the meeting took place in Florida. The image was actually taken from a public YouTube video. Christian Sanon is present along with a number of other alleged suspects.

I had little doubt that Sanon really believed, at least initially, that he was going to be prime minister, or president, or whatever. He had made that clear to me two years earlier. Was it another grift that spiraled out of control? Or was he just a convenient scapegoat for someone else's macabre plan? What it reminded me of was Petit Bois and the arrests made five months earlier.

Screenshot from a 2011 video from Christian Sanon titled "Dr. Christian Sanon on Corruption in Politics." Sanon's presidential ambitions date to at least 2010, after the devastating earthquake struck Haiti.

Screenshot from a 2011 video from Christian Sanon titled "Dr. Christian Sanon on Corruption in Politics." Sanon's presidential ambitions date to at least 2010, after the devastating earthquake struck Haiti.

Notice in the official government publication Le Moniteur concerning the creation of a new company, Vasco Gaz S.A. Dated October 31, 2017.

Notice in the official government publication Le Moniteur concerning the creation of a new company, Vasco Gaz S.A. Dated October 31, 2017.

Florida business registration of Vasco Gas LLC with Christian Sanon listed as manager. From sunbiz.org.

Florida business registration of Vasco Gas LLC with Christian Sanon listed as manager. From sunbiz.org.

Flyer from a March 18, 2019 meeting of the Diaspora Caribbean Republican Coalition listing Christian Sanon as a panelist.

Flyer from a March 18, 2019 meeting of the Diaspora Caribbean Republican Coalition listing Christian Sanon as a panelist.

Slide from a presentation made by the Haitian National Police claiming this was the meeting where the assassination was planned. The police said the meeting took place in the Dominican Republic. In fact, the meeting took place in Florida. The image was actually taken from a public YouTube video. Christian Sanon is present along with a number of other alleged suspects.

Slide from a presentation made by the Haitian National Police claiming this was the meeting where the assassination was planned. The police said the meeting took place in the Dominican Republic. In fact, the meeting took place in Florida. The image was actually taken from a public YouTube video. Christian Sanon is present along with a number of other alleged suspects.

THE IMPERSONATOR

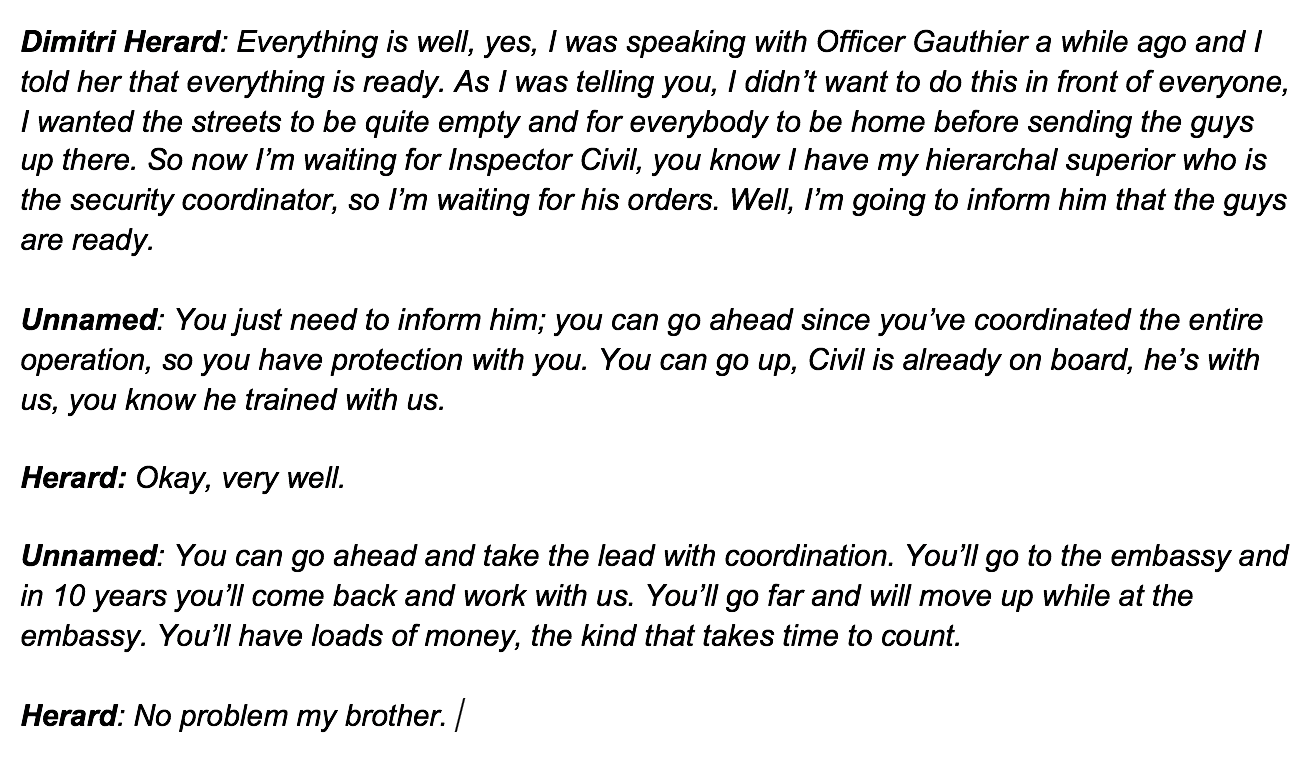

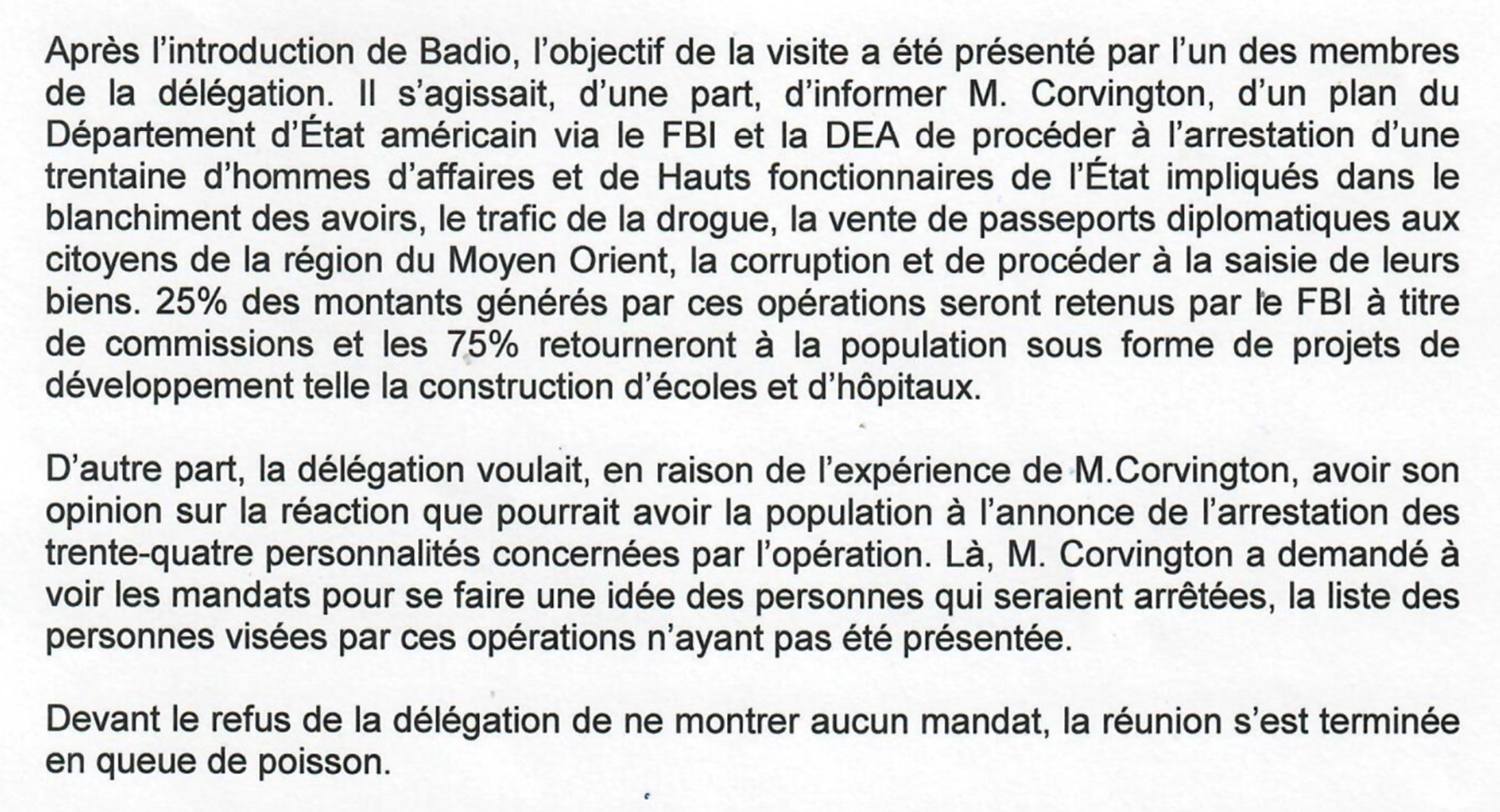

Transcript from an audio recording between Dimitri Herard, the chief of the president's security detail, and an unnamed individual. In another recording the unnamed individual identifies himself as Philippe MarcAndre, an alias. Civil refers to Jean Laguel Civil, the coordinator of all presidential security units and Herard's direct superior.

Transcript from an audio recording between Dimitri Herard, the chief of the president's security detail, and an unnamed individual. In another recording the unnamed individual identifies himself as Philippe MarcAndre, an alias. Civil refers to Jean Laguel Civil, the coordinator of all presidential security units and Herard's direct superior.

On February 6, 2021, Dimitri Herard spoke by telephone with a man identifying himself as Philippe MarcAndre, according to audio recordings released by the government after the arrests at Petit Bois. Herard, the head of the president’s security, agreed to send a contingent of troops under his command to the apartment complex that night in preparation for the following day, when president Jovenel Moïse would leave the palace and a new president would be sworn in. "You'll have loads of money," MarcAndre tells Herard.

Herard: So now I have another question for you, once I send the guys up tonight, you told me the installation would take place at 10 a.m. tomorrow morning.

MarcAndre: Yes, 10.

Herard: So, once I do that, what about President Jovenel? You told me about a warrant that you had on him, so that I could bring him to you.

MarcAndre: We’ll send the warrant to you on your phone and then you’ll come with him on the base. From there he’s the [foreigners’] responsibility.

Herard: Okay but when are you sending me the warrant? Because it is the legal aspect of the case, so don’t forget that if I don’t have a warrant and I’m doing certain things, I’m a terrorist.

MarcAndre: No don’t worry, the warrant is here. Gauthier is getting it right now, you’ll print it and the original is with the judge. Judge Noel. We’ll send you a number.

Herard: Judge Noel?

MarcAndre: Yes.

Herard: Okay, but let me explain myself Philippe, I’m starting to work for you all tonight, but starting tonight, I don’t have anything with me to protect myself, which is why the warrant is important to me.

MarcAndre: Okay, do you want me to send it to you on your phone?

Herard: Yes, please.

MarcAndre: Okay, I’ll send it now with the notice of receipt of the American embassy.

Herard: Okay, send it to me now and I’ll act now.

MarcAndre: Okay, no problem.

Former President Michel Martelly shakes hands with Dimitri Herard in Ecuador in July 2012. Image from Martelly's facebook page.

Former President Michel Martelly shakes hands with Dimitri Herard in Ecuador in July 2012. Image from Martelly's facebook page.

Herard, who studied at an elite Ecuadorian military university and had been trained in intelligence, made for an interesting co-conspirator. He had developed a close relationship with former president Michel Martelly, who had picked Jovenel Moïse as his successor. And, on Martelly’s recommendation, Herard had served as head of the National Palace General Security Unit (USGPN) in the years since Moïse had taken office.

If he was involved, it meant one of two things: either the president’s inner circle had turned on him, or he was doing counterintelligence. The fact that the president had publicly thanked him for thwarting the plot hinted at the latter. But, as the recordings made clear, without Herard’s involvement, there simply was no plan, or, at least, no ability to actually carry one out.

Had those arrested been misled from the beginning?

The plan had begun at least five months earlier. In late August, Marie Antoinette Gauthier, a doctor and former medical director of Haiti's general hospital, received a call from someone she didn’t know, a man identifying himself as Mark Philippe. He wanted to talk about the future of Haiti. He claimed to have support from the US government and wanted to help put together a transitional government. The two struck up something of a friendship, and often spoke for an hour or more in the evenings. Other members of Gauthier’s family also started speaking with Philippe, including her sister, a high-ranking inspector in the Haitian National Police. “He became almost part of the family,” Gauthier said, looking back months later.

Philippe told the Gauthiers that he was working with Daniel Whitman, a former State Department official who had served as a press officer at the US Embassy in Port-au-Prince from 2000 to 2001.

Still, Gauthier and her husband say they were skeptical. That is, until they spoke with Carolle Tranchant and her husband, Lynn Garrison, a former Canadian Air Force pilot, who convinced them otherwise. “Everyone thinks he is CIA,” Louis Buteau, Gauthier’s husband, told me. In the early 90s, following a coup that ousted the country’s first democratically elected president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, Garrison served as a political advisor to the leader of the military junta that seized power. Though he has previously denied being CIA, he has claimed to have ties with US intelligence agencies and among US politicians. Garrison is credited with being a source for the CIA’s early 90s allegation that Aristide suffered from mental illness.

November 2, 1993 article in The Independent about Lynn Garrison.

November 2, 1993 article in The Independent about Lynn Garrison.

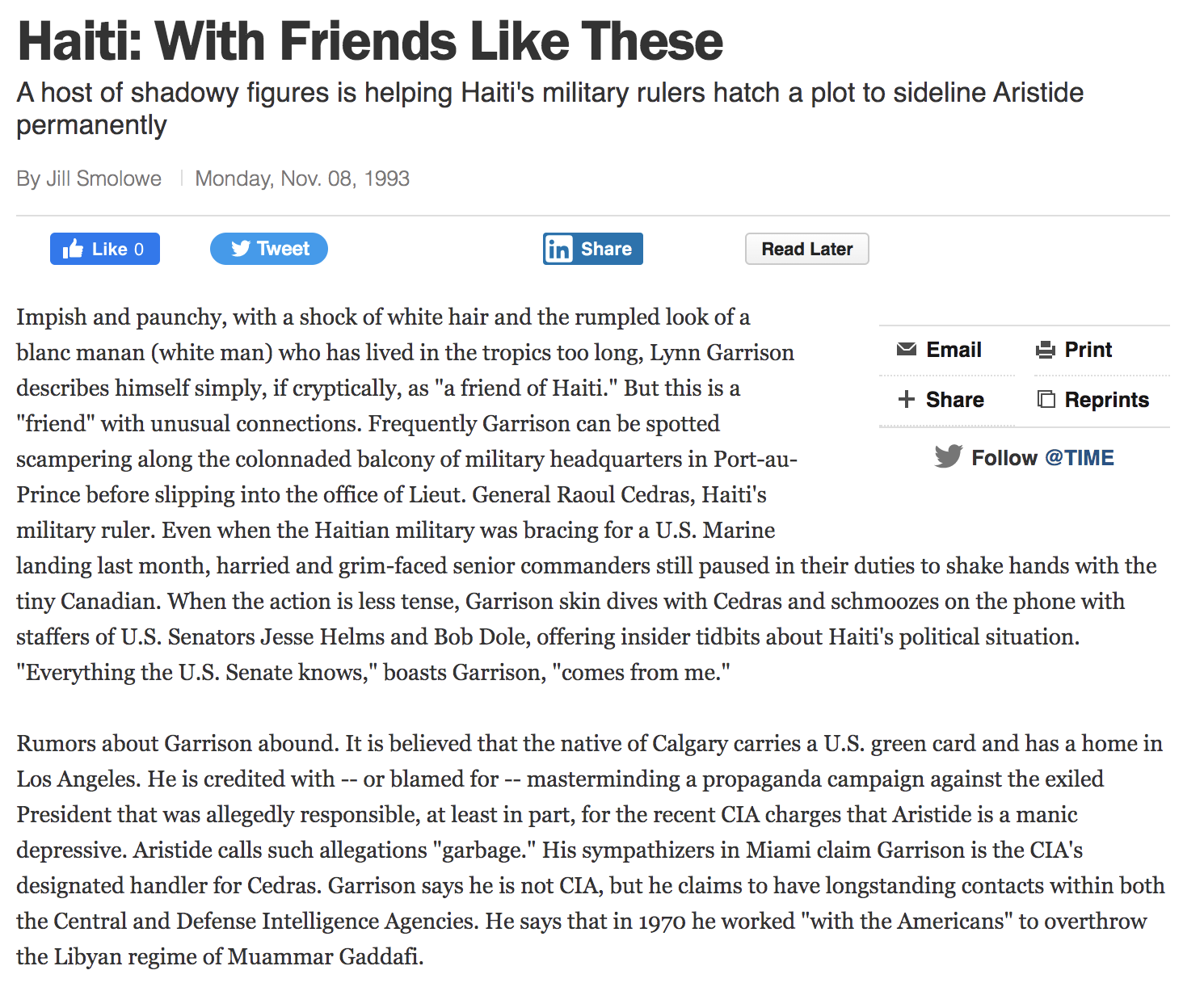

November 8, 1993 article in TIME about Lynn Garrison. The TIME and Independent articles came just weeks after the CIA briefed congress on Aristide's "psychological profile." At the time, the Clinton administration was discussing militarily intervening to restore Aristide to power, an effort adamantly opposed by Garrison, as well as a number of Senators, including Jesse Helms (R-NC). "Everything the U.S. Senate knows … comes from me,” Garrison told the reporter. After the CIA briefing, Helms told the press that Aristide was a “demonstrable killer” and a “psychopath.”

November 8, 1993 article in TIME about Lynn Garrison. The TIME and Independent articles came just weeks after the CIA briefed congress on Aristide's "psychological profile." At the time, the Clinton administration was discussing militarily intervening to restore Aristide to power, an effort adamantly opposed by Garrison, as well as a number of Senators, including Jesse Helms (R-NC). "Everything the U.S. Senate knows … comes from me,” Garrison told the reporter. After the CIA briefing, Helms told the press that Aristide was a “demonstrable killer” and a “psychopath.”

Believing this plan might actually be legitimate, the Gauthier's continued to speak with Philippe. He explained that they needed housing in Haiti for the plan, a place where they could hold meetings in confidence. Gauthier reached out to an old friend, Jean Marie Vorbe, whose company, Sogener, had been seized by the government the year prior. Vorbe, like many in the nation’s elite families, had financially backed Moïse’s presidential campaign, but by 2020, with his business gone and his family under threat of further legal issues, that relationship had been completely severed. Vorbe owned the Petit Bois Residences.

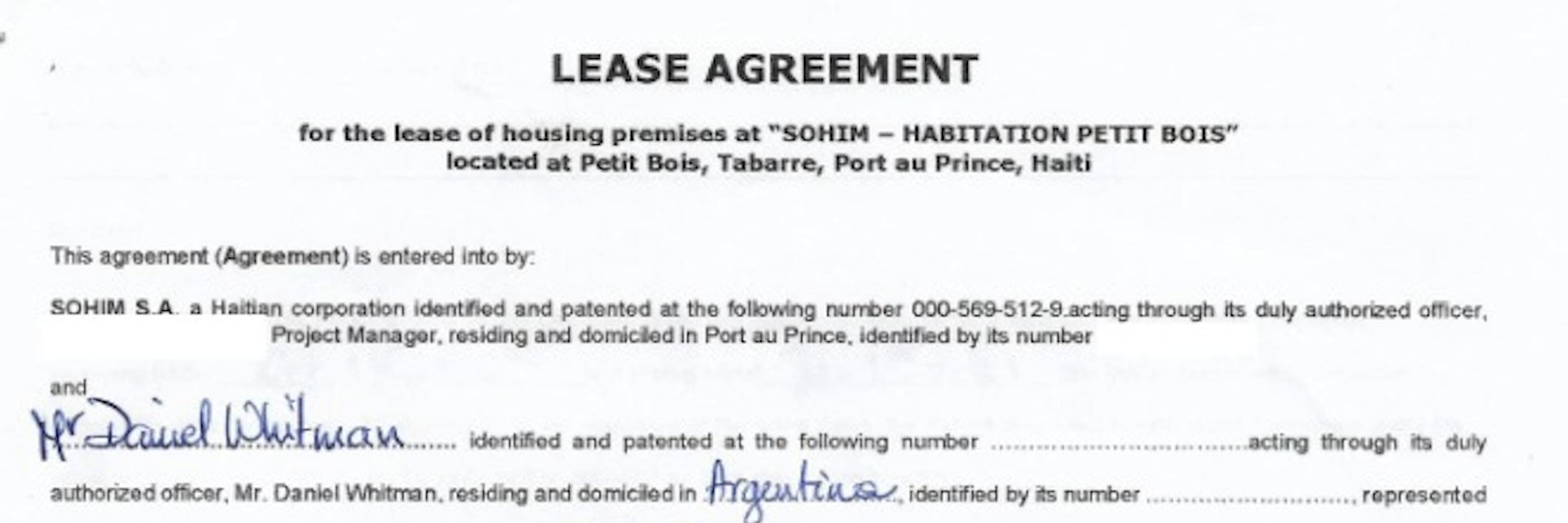

Part of a lease agreement for the Petit Bois apartments in the name of a Daniel Whitman domiciled in Argentina.

Part of a lease agreement for the Petit Bois apartments in the name of a Daniel Whitman domiciled in Argentina.

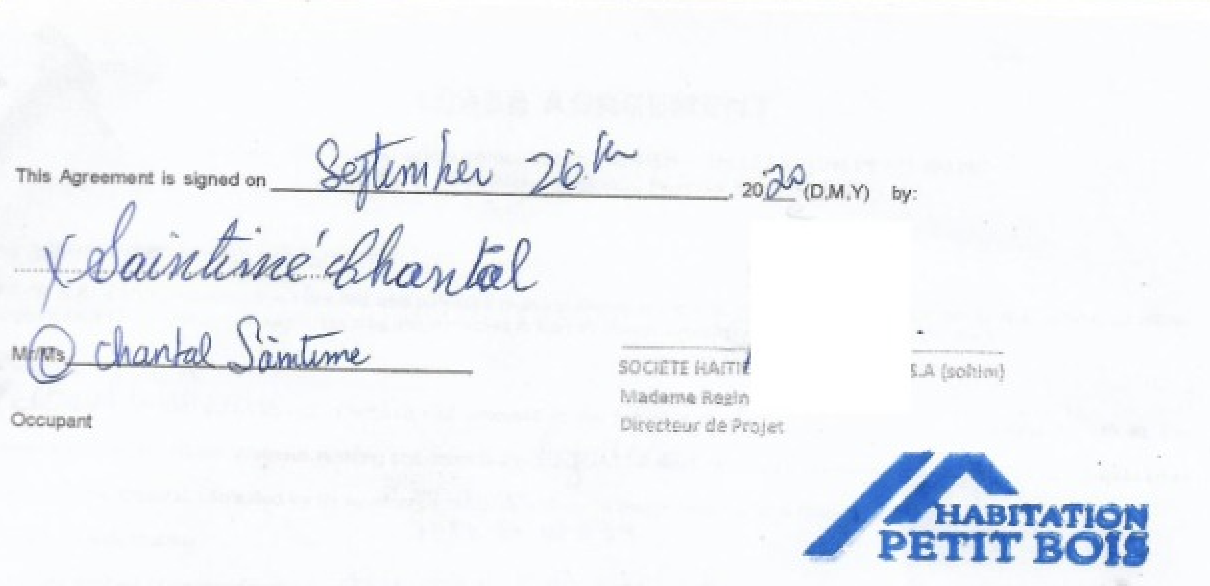

Chantal Saintime signs the lease agreement as a "representative" of Daniel Whitman. September 26, 2020.

Chantal Saintime signs the lease agreement as a "representative" of Daniel Whitman. September 26, 2020.

On September 26, 2020, Chantal Saintime, who presented herself as a representative of Daniel Whitman, signed a lease agreement for the use of 25 housing units. Saintime agreed to pay a $10,000 deposit, though the money did not come right away. Still, trusting that his old friend would come through with the money eventually, Vorbe agreed to let the group into the Petit Bois apartments. The first group moved in soon thereafter, in early October.

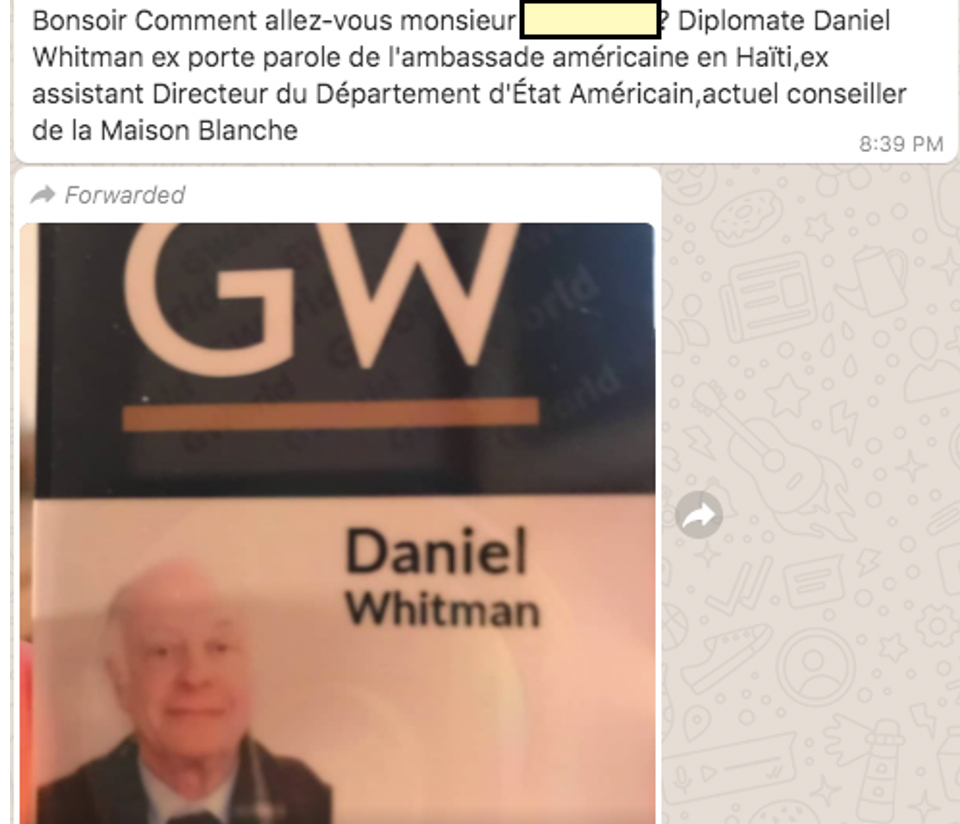

I first started hearing whispers of Whitman’s name about six weeks later, in mid-November. A source sent me a screenshot of a message they had received on WhatsApp.

WhatsApp message from an individual claiming to be Daniel Whitman and presenting himself as a current White House advisor. The individual included a photo of a George Washington University ID badge belonging to Whitman.

WhatsApp message from an individual claiming to be Daniel Whitman and presenting himself as a current White House advisor. The individual included a photo of a George Washington University ID badge belonging to Whitman.

“Good evening, how are you, [redacted]? Diplomat Daniel Whitman ex-spokesperson for the American embassy in Haiti, ex-assistant director of the American State Department, current adviser to the White House,” the message read in French. The person said they had rented an apartment in Tabarre, right near the US embassy, where there was a group working “for the smooth development of a new system of governance.” They urged my source to contact a former Haitian judicial official, Mario Beauvoir, to urgently discuss the matter.

The next month, I received another message asking about Whitman from a different source. It seemed that word was spreading. He was working for the State Department, or maybe it was the National Security Council; no, it was the White House, others said. Had President-Elect Joe Biden sent an emissary to evaluate “options” in Haiti? Nothing seemed to make any sense. The individual who had first told me about Whitman was skeptical. As far as they knew, nobody had ever met the former diplomat face-to-face. In fact, they had even warned one of those allegedly in touch with Whitman to be careful.

As he had discussed with the man calling himself Philippe MarcAndre, Dimitri Herard and the USGPN arrived at the Petit Bois apartments in the evening on February 6, 2021. But, they were not there to help arrest the president; they went to Petit Bois to arrest everyone staying there. When the photos of those arrested started circulating, the pieces started coming together. The individuals I had been told were meeting with Whitman had all been arrested, including Marie Antoinette Gauthier; her sister, the police inspector; a Supreme Court judge; and Chantal Saintime. The one person who was not arrested was Mario Beauvoir, who had apparently left the apartment complex earlier that day and — as of this writing — has not been seen or heard from in public since.

It was time to find the real Whitman.

It wasn’t difficult. I sent an email to his publicly listed American University email address and he responded seven minutes later. While Whitman was outraged by the general situation in Haiti, he categorically denied even knowing the names of those who had been arrested that morning. He had left Haiti after his posting in 2001 and had never returned, he said, though he had stayed in contact with a few friends and followed the situation some from Washington.

A week later, we met at the Bishop’s Garden in the shadow of the National Cathedral in Washington. Whitman, 75 years old with thinning white hair, showed up wearing a trench coat. “It makes for a better movie opening than a parking garage in Arlington,” he said with a wry smile that seemed to rarely leave his face. It was a reference to "Deep Throat," the anonymous source that drove the Washington Post’s Watergate coverage. Despite the theatrics, he was not, nor was he trying to be, Deep Throat. But we were meeting in person because I had a hunch who had been impersonating him, and it seemed like Whitman’s name hadn’t simply been pulled out of thin air.

FROM ONE ASSASSINATION TO THE NEXT

In early October 2020, Whitman received a phone call from someone he had not seen in nearly 20 years, a man named Philippe Markington. They had last met in the aftermath of the April 2000 assassination of Haiti’s most prominent journalist, Jean Léopold Dominique, when Whitman was still at the US Embassy in Haiti. At the time, Markington presented himself to the police as a witness to the murder. He quickly became a suspect. Whitman, who had been a guest on Dominique’s radio show in the months before the assassination, met Markington at his embassy office. It wasn't their first encounter. Markington, portraying himself as a government insider, came to the office frequently with tales of "hit-lists" and other supposed evidence of government misdeeds.

It is unclear why Markington was allowed to leave prison to meet with Whitman. In a book Whitman wrote after leaving Haiti, he remembered Markington having visible injuries that he assumed were from being tortured. Markington said that he was being pressured to blame Whitman and the CIA for the assassination. They met two or three times over a short period of time, Whitman wrote, always with approval from his superiors.

Markington surely never forgot the encounters.

The assassination of Dominique was a politically charged and high-profile affair, the subject of an award-winning 2003 documentary by Jonathan Demme, director of "The Silence of the Lambs." It came at the end of president René Préval's first term, in the spring of 2000, and, in many ways, marked a turning point in his relationship with his political mentor and predecessor, Jean-Bertrand Aristide. The assassination was quickly linked to ostensible allies of Aristide, who was preparing to run in upcoming elections for a second mandate, specifically a powerful senator and former military officer, Dany Toussaint. For his part, Toussaint pointed a finger at Whitman and questioned the diplomat’s relationship with Markington. Why was someone at the US Embassy meeting a suspect? Toussaint asked publicly. Whitman says that the Haitian police even had a file on him as a suspect in the case. The assassins allegedly drove a white Jeep, a similar vehicle to the one Whitman used.

Toussaint, who received CIA training, had begun to distance himself from Aristide and his Lavalas party well before the assassination however, and he played an active role with the US, other former soldiers, and the Haitian elite, in undermining the government. Those efforts, stoked by the allegations around Dominique's assassination, succeeded in 2004, when Aristide was overthrown in a coup d’etat. Though many blamed the Aristide government for blocking the Dominique investigation, the case went nowhere even after his ouster. “[It] obviously raises the specter that the whole thing was a charade from the beginning,” Brian Concannon, who investigated the case at the time with the Bureau des Avocats Internationaux, later said. Twenty years after Dominique’s death, the masterminds of that killing have never been identified, a warning to those hoping for quick results after the Moïse assassination.

As for Markington, he was indicted in 2003. He spent less than two years in prison before managing to escape along with two other codefendants. While they were both recaptured, Markington managed to flee the country and eventually settled in Argentina, where he lived out of sight for more than a decade. That changed under the presidency of Michel Martelly. A new judge, Yvickel Dabrésil — the same judge who would be arrested on February 7, 2021 — reopened the investigation and issued a series of new indictments, targeting a number of former officials perceived as close to Aristide, including Markington. In June 2014, Markington was repatriated from Argentina to Haiti. He’s been in a jail in the capital ever since.

Was this the man impersonating Whitman?

I reached out to someone who had worked the Dominique case all those years ago. “When [Markington] came to my office to give me info, I had two choices: believe him or arrest him,” remembered Jean-Sénate Fleury, a former judge and prosecutor. “I arrested him.”

Clearly Fleury didn’t believe the information that Markington provided. “I know for sure he was working for the Haitian police as an informant [at the time of the assassination]” he said. There was always something more going on, he suspected. Fleury said he had long wondered how Markington had managed to get to Argentina in the first place. He has previously suggested it was the CIA. “Markington is someone very well connected,” he told me. I asked if Fleury thought it could have been Markington impersonating Whitman. He had no direct knowledge. But, he added, Markington was a talker. “With his speech, he can drive you anywhere. If something is white, he will tell you it is black — and you will believe it.”

When Markington called Whitman in the fall of 2020, he said that he and others in Haiti were planning a transitional government, and he wanted Whitman to come to Haiti for the inauguration in early 2021. He said they had rented a house near the US Embassy and invited Whitman there. Whitman told me he declined, and put the issue behind him. Still, Markington had continued to call, almost always from a different number.

After the February 7 arrests, journalist Roudy Metellus took to his radio program’s airwaves to explain that he had been contacted by someone claiming to be Whitman. The person had reached out using a number with a 786 area code — South Florida. But, he said, when he got a friend to make contact with the number, the person on the other end didn’t even speak English. The real Whitman may not have had anything to do with the plot, but he did hold the key to finding the impersonator. Philippe Markington had left him a voicemail using that same 786 phone number. It appeared that Markington, still in a jail cell at the National Penitentiary, had been the one impersonating Whitman. And, it seems likely he was also Philippe MarcAndre, the person on the other end of the conversation with the president’s chief of security, Dimitri Herard.

In another conversation on February 6, Herard speaks with the man identifying himself as MarcAndre, who explains that the US Embassy had signed off on the arrest of President Moïse. Herard presses, asking who specifically had approved this, but MarcAndre demurs and quickly hangs up the phone. Herard continued to record.

“He had to go and turn off the phone. He’s in Haiti!” Herard says.

“He’s in Haiti!” Someone can be heard saying in the background, before everyone starts to laugh.

FROM ONE ASSASSINATION TO THE NEXT

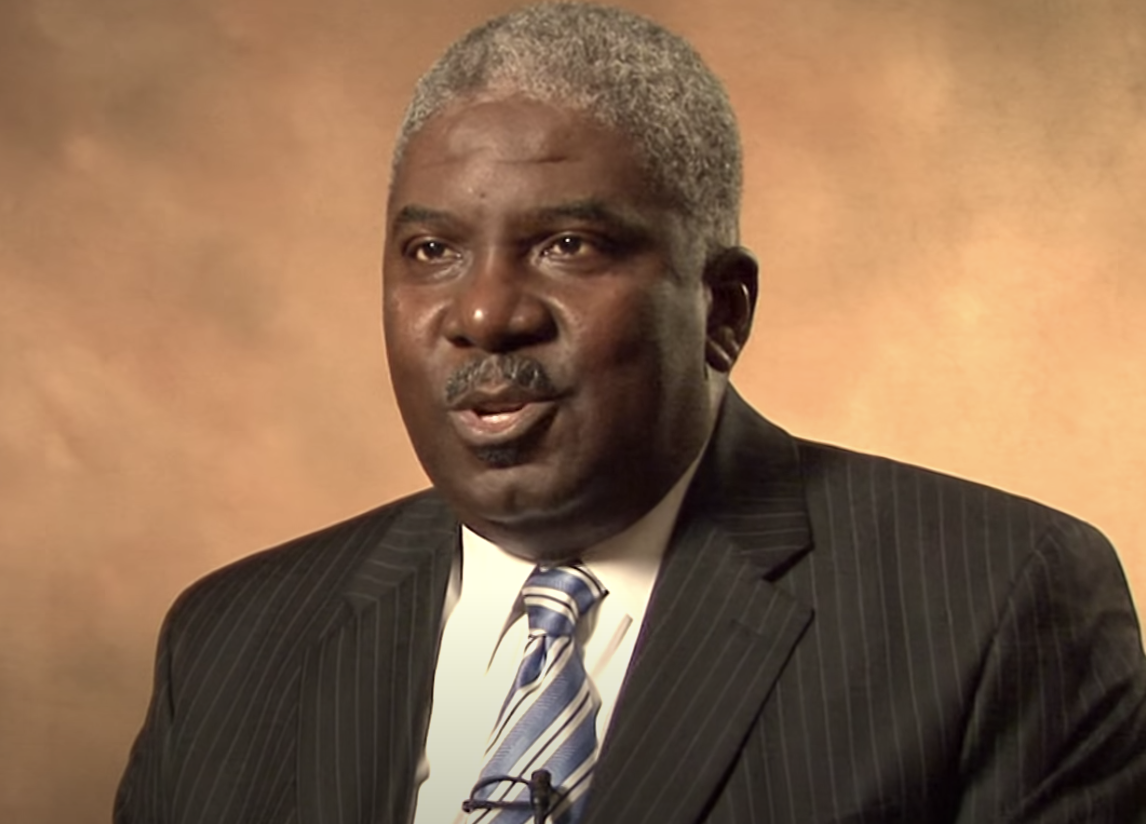

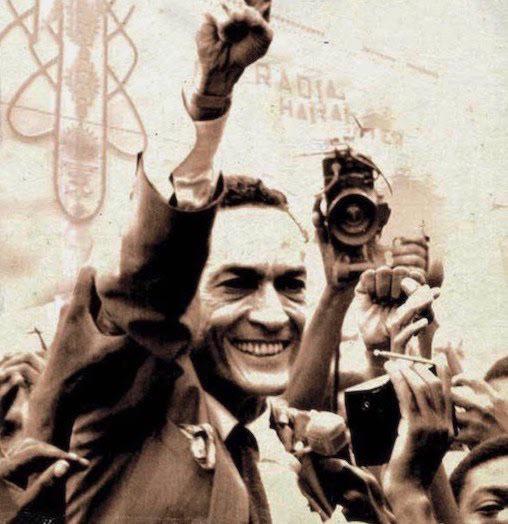

Jean Léopold Dominique

Jean Léopold Dominique

In early October 2020, Whitman received a phone call from someone he had not seen in nearly 20 years, a man named Philippe Markington. They had last met in the immediate aftermath of the April 2000 assassination of Haiti’s most prominent journalist, Jean Léopold Dominique, when Whitman was still at the US Embassy in Haiti. At the time, Markington presented himself to the police as a witness to the murder. He quickly became a suspect. Whitman, who had been a guest on Dominique’s radio show just weeks before the assassination, met Markington at his embassy office. It wasn't their first encounter. Markington, portraying himself as a government insider, came to the office frequently with tales of "hit-lists" and other supposed evidence of government misdeeds.

It is unclear why Markington was allowed to leave prison in the first place. In a book Whitman wrote after leaving Haiti, he remembered Markington having visible injuries that he assumed were from being tortured. Markington said that he was being pressured to blame Whitman and the CIA for the assassination. They met two or three times over a short period of time, Whitman wrote, always with approval from his superiors.

Markington surely never forgot the encounters.

The assassination of Dominique was a politically charged and high-profile affair, the subject of an award-winning documentary by Jonathan Demme, director of "The Silence of the Lambs". It came at the end of president René Préval's first term, in the spring of 2000, and, in many ways, marked a turning point in his relationship with his political mentor and predecessor, Jean-Bertrand Aristide. The assassination was quickly linked to allies of Aristide, who was preparing to run in upcoming elections for a second mandate, specifically a powerful senator and former military officer, Dany Toussaint. For his part, Toussaint pointed a finger at Whitman and questioned the diplomat’s relationship with Markington. Why was someone at the US Embassy meeting a suspect? Toussaint asked publicly. Whitman says that the Haitian police even had a file on him as a suspect in the case. The assassins allegedly drove a white Jeep, a similar vehicle to the one Whitman used.

Toussaint, who received CIA training, had begun to distance himself from Aristide and his Lavalas party well before the assassination however, and he played an active role with the US, other former soldiers, and the Haitian elite, in undermining the government. Those efforts, stoked by the allegations around Dominique's assassination, succeeded in 2004, when Aristide was overthrown in a coup d’etat. Though many blamed the Aristide government for blocking the Dominique investigation, the case went nowhere even after his ouster. “[It] obviously raises the specter that the whole thing was a charade from the beginning,” Brian Concannon, who investigated the case at the time with the Bureau des Avocats Internationaux, later said. Twenty years after Dominique’s death, the masterminds of that killing have never been identified, a warning to those hoping for quick results after the Moïse assassination.

As for Markington, he was indicted in 2003. He spent less than two years in prison before managing to escape along with two other codefendants. While they were both recaptured, Markington managed to flee the country and eventually settled in Argentina, where he lived out of sight for more than a decade. That changed under the presidency of Michel Martelly. A new judge, Yvickel Dabrésil — the same judge who would be arrested on February 7, 2021 — reopened the investigation and issued a series of new indictments, targeting a number of former officials perceived as close to Aristide, including Markington. In June 2014, Markington was repatriated from Argentina to Haiti. He’s been in a jail in the capital ever since.

Was this the man impersonating Whitman?

I reached out to someone who had worked the Dominique case all those years ago. “When [Markington] came to my office to give me info, I had two choices: believe him or arrest him,” remembered Jean-Sénate Fleury, a former judge and prosecutor. “I arrested him.”

Clearly Fleury didn’t believe the information that Markington provided. “I know for sure he was working for the Haitian police as an informant [at the time of the assassination]” he said. There was always something more going on, he suspected. Fleury said he had long wondered how Markington had managed to get to Argentina in the first place. He has previously suggested it was the CIA. “Markington is someone very well connected,” he told me. I asked if Fleury thought it could have been Markington impersonating Whitman. He had no direct knowledge. But, he added, Markington was a talker. “With his speech, he can drive you anywhere. If something is white, he will tell you it is black — and you will believe it.”

When Markington called Whitman in the fall of 2020, he said that he and others in Haiti were planning a transitional government, and he wanted Whitman to come to Haiti for the inauguration in early 2021. He said they had rented a house near the US Embassy and invited Whitman there. Whitman told me he declined, and put the issue behind him. Still, Markington had continued to call, almost always from a different number.

After the February 7 arrests, journalist Roudy Metellus took to his radio program’s airwaves to explain that he had been contacted by someone claiming to be Whitman. The person had reached out using a number with a 786 area code — South Florida. But, he said, when he got a friend to make contact with the number, the person on the other end didn’t even speak English. The real Whitman may not have had anything to do with the plot, but he did hold the key to finding the impersonator. Philippe Markington had left him a voicemail using that same 786 phone number. It appeared that Markington, still in a jail cell at the National Penitentiary, had been the one impersonating Whitman. And, it seems likely he was also Philippe MarcAndre, the person on the other end of the conversation with the president’s chief of security, Dimitri Herard.

In another conversation on February 6, Herard speaks with the man identifying himself as MarcAndre, who explains that the US Embassy had signed off on the arrest of President Moïse. Herard presses, asking who specifically had approved this, but MarcAndre demurs and quickly hangs up the phone. Herard continued to record.

“He had to go and turn off the phone. He’s in Haiti!” Herard says.

“He’s in Haiti!” Someone can be heard saying in the background, before everyone starts to laugh.

INVESTIGATING PETIT BOIS

As I investigated Markington and the Petit Bois affair, I spoke to a Haitian politician who had received a message in February 2020 from a “Peter White” claiming to work for Dan Whitman. Pressed over his identity, “Peter” said his name was actually Paul Philippe, and sent a picture. It was a picture of Philippe Markington. In May 2020, the politician received an email claiming to be from Whitman, who presented himself as a private advisor to Donald Trump. The next month, another email came, this one explicitly talking about plans for a transitional government. The Haitian politician didn’t buy the story and stopped all communication. Well before Markington had established any connection to those arrested at Petit Bois, he had been fishing around among Haiti’s political class, hoping that someone would take the bait. It remains unclear if Markington truly believed in what he was saying, or if the entire thing was a ruse from the beginning. But, by the fall of 2020, an actual plan had begun to take shape.

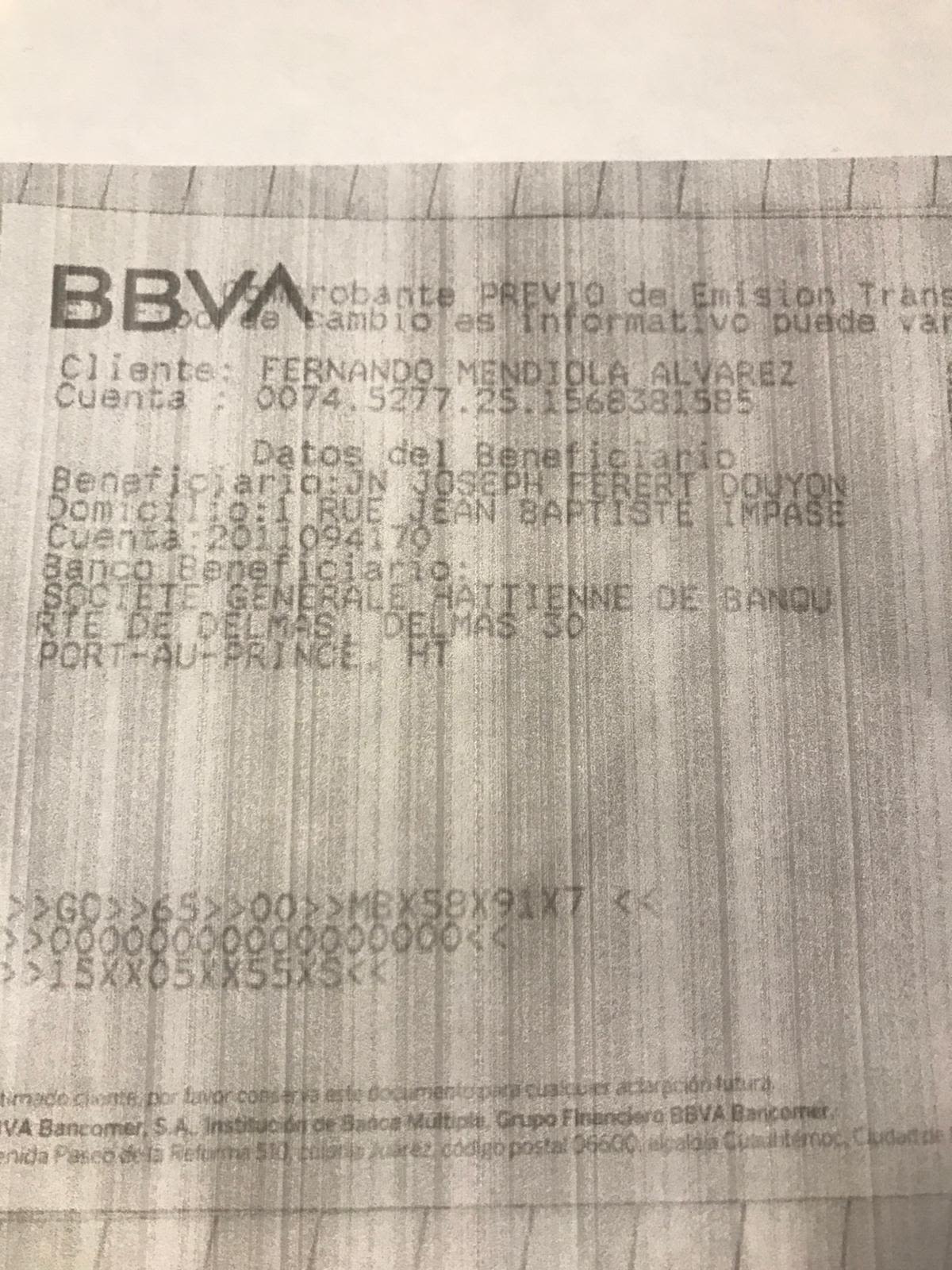

The first person to move into the Petit Bois apartments was Mario Beauvoir, the former judicial official; he took up residence there in early October. Whitman, however, never materialized. Nor did the money he was supposed to provide. But, from his jail cell, Markington seemed to have a plan. In a video he sent to a contact in early-October, a woman speaking Spanish, apparently in Mexico, can be seen counting stacks of crisp $100 bills, $15,000 in total. “It is for Philippe Markington,” the woman says in Spanish. On October 7, according to a money transfer confirmation obtained as part of this investigation, $30,000 was transferred from a bank in Veracruz, Mexico to Haiti. The transfer was made to a man named Jean Joseph Ferert Douyon, whose Facebook and LinkedIn profiles identify him as the CEO of a small construction company. (Douyon did not respond to multiple calls and messages seeking comment.)

Douyon received the money and then, according to bank records, transferred nearly $10,000 as a partial (and very late) down payment on the Petit Bois apartments. According to sources consulted for this investigation, that was the only money ever paid for the houses. It is unclear what happened to the remaining $20,000.

According to some of those involved, the initial plan involved Wendelle Coq Thélot, a Supreme Court judge and the same person Sanon had mentioned to me in 2019, taking over as provisional president. She had even been given a speech and, together with Beauvoir, had drafted a document outlining the contours of the planned transition. Soon after, however, Coq Thélot apparently had a video call with someone she was expecting to be Daniel Whitman. It wasn’t, and the judge seemed to get spooked. After being in regular contact with Markington for more than a month, she backed out in early November. Beauvoir then approached Judge Dabresil, who moved into the Petit Bois apartments himself along with multiple family members.

In early November, Markington, whose real identity apparently was still unknown to at least most of those involved, sent a 10-point plan for a transition. It included amnesty for officials in the Moïse administration and also reserved at least three ministries to be led by Parti Haïtien Tèt Kale (PHTK) — the party of President Moïse and his predecessor, Michel Martelly. Inside Petit Bois, some believed the government was actively engaged in negotiations for its own peaceful exit from power.

Markington, claiming to be Whitman's emissary and still using a pseudonym, began to tell contacts that he was in touch with the president’s security officials. On November 15, records show, the Haitian cell phone registered to Markington received a call from Jean Laguel Civil, the president’s security coordinator. The next day, records show a five-minute call between Markington and a phone registered to Dimitri Herard. Around this same time, the meetings at the Petit Bois complex multiplied; more prominent figures began to show up, including members of the Haitian police.

Meanwhile, the government was implementing a major personnel shake up. On November 16, Moïse appointed a new police chief, Leon Charles, who had been serving in Washington as the country’s ambassador to the OAS. While there, he had helped ensure continued diplomatic support for Moïse even after he began ruling by decree the year prior. The changes reflected the growing influence within the government of Laurent Lamothe, the former prime minister under Martelly. Charles made multiple visits to the Petit Bois complex soon after taking the position. The Moïse administration, however, already had their eyes on Petit Bois.

In late November, facing continued and widespread protests, Moise issued a presidential decree that expanded the definition of terrorism to include common civil disobedience tactics and created a new intelligence agency that would respond directly to the executive branch. According to multiple sources, the driving force behind this new agency was, again, Lamothe. When he had been prime minister, he had desperately wanted to establish a new intelligence agency. He had even created an informal body within the police, but responsive primarily to the prime minister’s office, that functioned as an intelligence agency. The man he tasked with leading the effort had been Leon Charles. Now, years later, with the Agence Nationale d’Intelligence (ANI) formalized and Charles serving as police chief, it seemed that Lamothe finally had what he was looking for. A plot against the president provided the perfect justification.

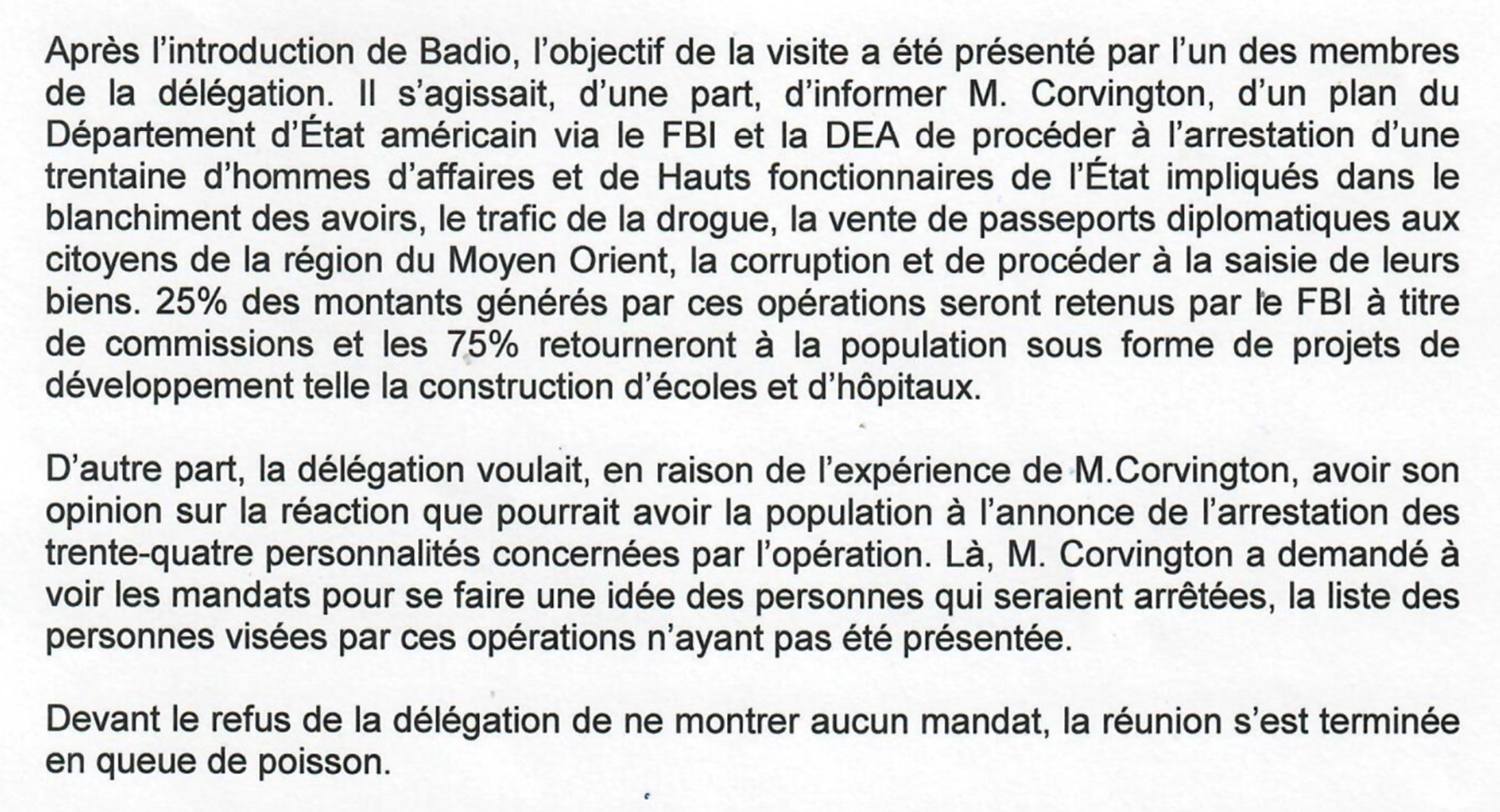

Around the same time, Rony Colin, a businessman and former mayor of the municipality of Croix du Bouquet, came to the Petit Bois apartments for a meeting. According to a source who was there, Colin told them that the Moïse administration was aware of the plan and was not going to go along with it. (Colin did not respond to a request for comment for this article.) The US Embassy was also aware of what was taking place. In early December, a Haitian government official who had been approached by Mario Beauvoir said he had alerted the embassy that there was a group claiming US support for arresting Moïse. But the Petit Bois plan went forward undeterred. The embassy and State Department did not respond to any specific questions concerning Petit Bois or the assassination.

As the calendar turned to 2021, the political and security situation on the ground in Haiti was reaching a breaking point. Groups of armed civilians, operating under an alliance called the "G9" and led by a former Haitian police officer, Jimmy Cherizier, had seized control over large tracts of the capital. Kidnappings were skyrocketing. Over the previous two-plus years, human rights organizations had documented more than a half-dozen massacres, resulting in hundreds of deaths. And, they alleged, the G9 was receiving support from high-level government officials. The United States sanctioned Cherizier, as well as two ministers in Moïse’s administration, for their alleged involvement in the deaths. The economy was cratering. Years of protests, and an opposition-led program of Peyi Lok — country lock — had effectively shut down most commerce. On top of all this, the Haitian National Police was collapsing due to its increasing politicization. A group of disgruntled cops had begun taking to the streets themselves in protest, often marching side by side with armed civilians. Many officers, including Herard, had started lucrative side gigs to provide private security.

In January, the president issued a direct warning, not to the parties responsible for the massacres, but to his political opponents who he alleged were behind every protest. The new intelligence agency had been the subject of intense criticism, but a defiant Moïse claimed that it was already operational. “We have already started to monitor a lot of things in the country,” he told the press on January 19. He said the government had created the new intelligence agency in order to monitor the “vagabonds” in the country. “When someone uses their money to destabilize the country, it is terrorism,” the president said. “We are watching you, we will come for you,” he threatened.

Those involved with Petit Bois, however, seemed to believe that their plan had official support. According to the testimony of some of the arrestees, the Haitian police actually provided security at the apartment complex for nearly a month in the lead up to February 7. And in late December the group was approached by Edouard Ambroise, who presented himself as an advisor to the president. There is no evidence he was. In fact, before joining with those in Petit Bois, he had been actively involved with Sanon for months. Sanon too had been hoping to replace the president come February 7, but, in the final months, his own efforts were pushed aside in favor of the Petit Bois plan. Ambroise had his hands in both efforts.

On February 5, Dimitri Herard recorded a conversation with the police inspector involved in Petit Bois:

Inspector Gauthier: Hello?

Herard: Sorry, Inspector, there were people with me so I couldn’t answer.

IG: Oh okay, I thought that might be the case. Listen I needed you, do you know of a certain Edouard Ambroise? I’ve been told he’s a friend of [Civil].

Herard: Okay, a friend of Commandant Civil.

IG: Yes, I’ve been told he has an access card to the palace already. I’ve been told that he will be the one making the connection between you and I.

Ambroise's involvement hints at the overlap between the two parallel efforts to replace Moïse. He was one of the first people that Markington, the man impersonating the State Department officer from his jail cell, spoke to after the arrests at Petit Bois. Five months later, he was in touch with key suspects in the immediate aftermath of the president's killing. Ambroise, however, was not the only actor connected to the assassination and those arrested at Petit Bois.

INVESTIGATING PETIT BOIS

As I investigated Markington and the Petit Bois affair, I spoke to a Haitian politician who had received a message in February 2020 from a “Peter White” claiming to work for Dan Whitman. Pressed over his identity, “Peter” said his name was actually Paul Philippe, and sent a picture. It was a picture of Philippe Markington. In May 2020, the politician received an email claiming to be from Whitman, who presented himself as a private advisor to Donald Trump. The next month, another email came, this one explicitly talking about plans for a transitional government. The Haitian politician didn’t buy the story and stopped all communication. Well before Markington had established any connection to those arrested at Petit Bois, he had been fishing around among Haiti’s political class, hoping that someone would take the bait. It remains unclear if Markington truly believed in what he was saying, or if the entire thing was a ruse from the beginning. But, by the fall of 2020, an actual plan had begun to take shape.

The first person to move into the Petit Bois apartments was Mario Beauvoir, the former judicial official; he took up residence there in early October. Whitman, however, never materialized. Nor did the money he was supposed to provide. But, from his jail cell, Markington seemed to have a plan. In a video he sent to a contact in early-October, a woman speaking Spanish, apparently in Mexico, can be seen counting stacks of crisp $100 bills, $15,000 in total. “It is for Philippe Markington,” the woman says in Spanish. On October 7, according to a money transfer confirmation obtained as part of this investigation, $30,000 was transferred from a bank in Veracruz, Mexico to Haiti. The transfer was made to a man named Jean Joseph Ferert Douyon, whose Facebook and LinkedIn profiles identify him as the CEO of a small construction company. (Douyon did not respond to multiple calls and messages seeking comment.)

Douyon received the money and then, according to bank records, transferred nearly $10,000 as a partial (and very late) down payment on the Petit Bois apartments. According to sources consulted for this investigation, that was the only money ever paid for the houses. It is unclear what happened to the remaining $20,000.

According to some of those involved, whose identities are being withheld out of fears of safety, the initial plan involved Wendelle Coq Thélot, a Supreme Court judge and the same person Sanon had mentioned to me in 2019, taking over as provisional president. She had even been given a speech and, together with Beauvoir, had drafted a document outlining the contours of the planned transition. Soon after, however, Coq Thélot apparently had a video call with someone she was expecting to be Daniel Whitman. It wasn’t, and the judge seemed to get spooked. After being in regular contact with Markington for more than a month, she backed out in early November. Beauvoir then approached Judge Dabresil, who moved into the Petit Bois apartments himself along with multiple family members.

In early November, Markington, whose real identity apparently was still unknown to at least most of those involved, sent a 10-point plan for a transition. It included amnesty for officials in the Moïse administration and also reserved at least three ministries to be led by Parti Haïtien Tèt Kale (PHTK) — the party of President Moïse and his predecessor, Michel Martelly. Inside Petit Bois, some believed the government was actively engaged in negotiations for its own peaceful exit from power.

Markington, claiming to be Whitman's emissary and still using a pseudonym, began to tell contacts that he was in touch with the president’s security officials. On November 15, records show, the Haitian cell phone registered to Markington received a call from Jean Laguel Civil, the president’s security coordinator. The next day, records show a five-minute call between Markington and a phone registered to Dimitri Herard. Around this same time, the meetings at the Petit Bois complex multiplied; more prominent figures began to show up, including members of the Haitian police.

Meanwhile, the government was implementing a major personnel shake up. On November 16, Moïse appointed a new police chief, Leon Charles, who had been serving in Washington as the country’s ambassador to the OAS. While there, he had helped ensure continued diplomatic support for Moïse even after he began ruling by decree the year prior. The changes reflected the growing influence within the government of Laurent Lamothe, the former prime minister under Martelly. Charles made multiple visits to the Petit Bois complex soon after taking the position. The Moïse administration, however, already had their eyes on Petit Bois.

In late November, facing continued and widespread protests, Moïse issued a presidential decree that expanded the definition of terrorism to include common civil disobedience tactics and created a new intelligence agency that would respond directly to the executive branch. According to multiple sources, the driving force behind this new agency was, again, Lamothe. When he had been prime minister, he had desperately wanted to establish a new intelligence agency. He had even created an informal body within the police, but responsive primarily to the prime minister’s office, that functioned as an intelligence agency. The man he tasked with leading the effort had been Leon Charles. Now, years later, with the Agence Nationale d’Intelligence (ANI) formalized and Charles serving as police chief, it seemed that Lamothe finally had what he was looking for. A plot against the president provided the perfect justification.

Around the same time, Rony Colin, a businessman and former mayor of the municipality of Croix du Bouquet, came to the Petit Bois apartments for a meeting. According to a source who was there, Colin told them that the Moïse administration was aware of the plan and was not going to go along with it. (Colin did not respond to a request for comment for this article.) The US Embassy was also aware of what was taking place. In early December, a Haitian government official, who had been approached by Mario Beauvoir, said he had alerted the embassy that there was a group claiming US support for arresting Moïse. But the Petit Bois plan went forward undeterred.

As the calendar turned to 2021, the political and security situation on the ground in Haiti was reaching a breaking point. Groups of armed civilians, operating under an alliance called the "G9" and led by a former Haitian police officer, Jimmy Cherizier, had seized control over large tracts of the capital. Kidnappings were skyrocketing. Over the previous two-plus years, human rights organizations had documented more than a half-dozen massacres, resulting in hundreds of deaths. And, they alleged, the G9 was receiving support from high-level government officials. The United States sanctioned Cherizier, as well as two ministers in Moïse’s administration, for their alleged involvement in the deaths. The economy was cratering. Years of protests, and an opposition-led program of Peyi Lok — country lock — had effectively shut down most commerce. On top of all this, the Haitian National Police was collapsing due to its increasing politicization. A group of disgruntled cops had begun taking to the streets themselves in protest, often marching side by side with armed civilians. Many officers, including Herard, had started lucrative side gigs to provide private security.

In January, the president issued a direct warning, not to those parties responsible for the massacres, but to his political opponents who he alleged were behind every protest. The new intelligence agency had been the subject of intense criticism, but a defiant Moïse claimed that it was already operational. “We have already started to monitor a lot of things in the country,” he told the press on January 19. He said the government had created the new intelligence agency in order to monitor the “vagabonds” in the country. “When someone uses their money to destabilize the country, it is terrorism,” the president said. “We are watching you, we will come for you,” he threatened.

Those involved with Petit Bois, however, seemed to believe their plan had official support. According to the testimony of some of those arrested, the Haitian police actually provided security at the apartment complex for nearly a month in the lead up to February 7. And in late December the group was approached by Edouard Ambroise, who presented himself as an advisor to the president. There is no evidence he was. In fact, before joining with those in Petit Bois, he had been actively involved with Sanon for months. Sanon too had been hoping to replace the president come February 7, but, in the final months, his own efforts were pushed aside in favor of the Petit Bois plan. Ambroise had his hands in both efforts.

On February 5, Dimitri Herard recorded a conversation with the police inspector involved in Petit Bois:

Inspector Gauthier: Hello?

Herard: Sorry, Inspector, there were people with me so I couldn’t answer.

IG: Oh okay, I thought that might be the case. Listen I needed you, do you know of a certain Edouard Ambroise? I’ve been told he’s a friend of [Civil].

Herard: Okay, a friend of Commandant Civil.

IG: Yes, I’ve been told he has an access card to the palace already. I’ve been told that he will be the one making the connection between you and I.

Ambroise's involvement hints at the overlap between the two parallel efforts to replace Moïse. He was one of the first people that Markington, the man impersonating the State Department officer from his jail cell, spoke to after the arrests at Petit Bois. Five months later, he was in touch with key suspects in the immediate aftermath of the president's killing. Ambroise, however, was not the only actor connected to the assassination and those arrested at Petit Bois.

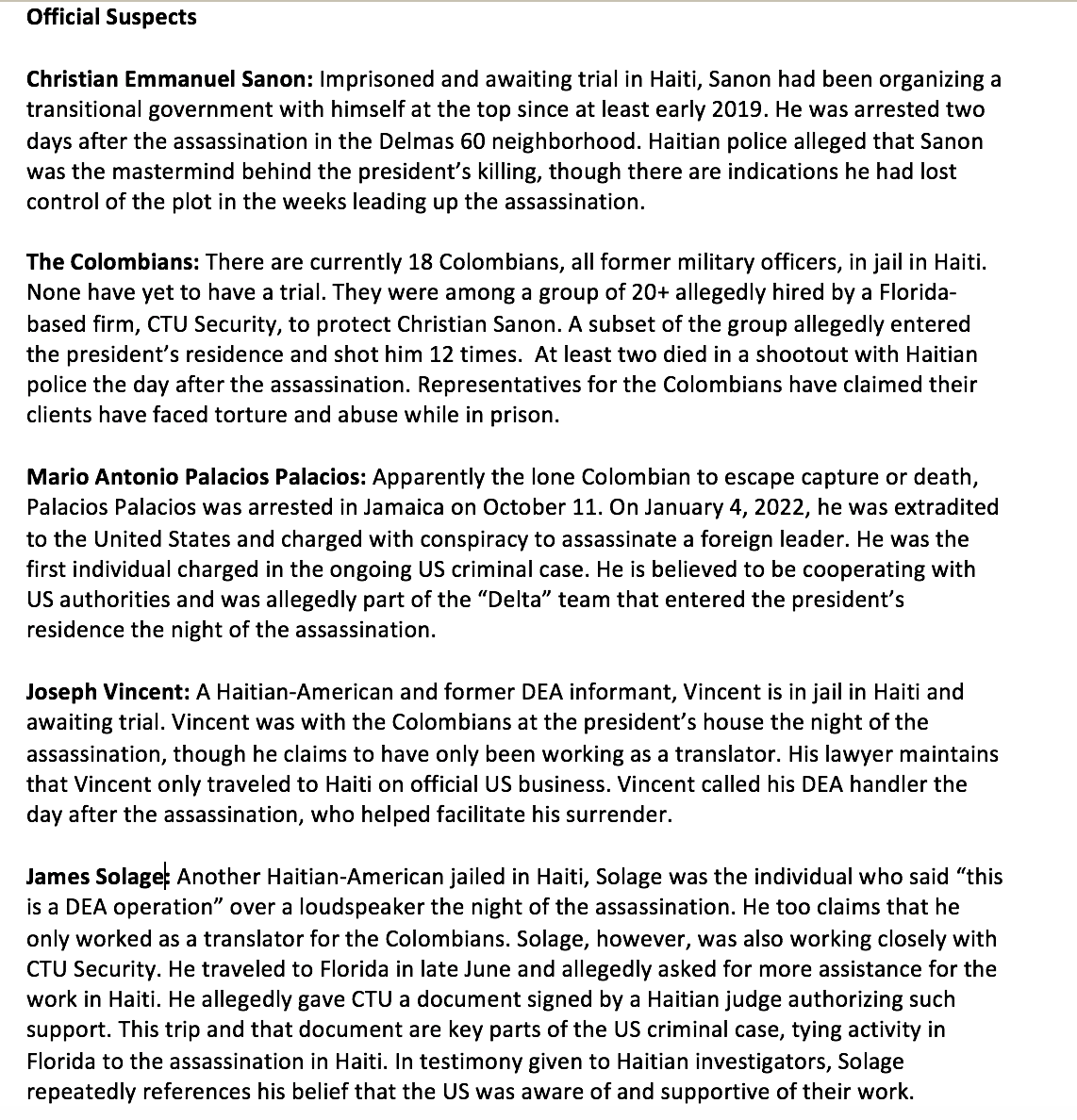

THE MISSING LINK

Altogether, 18 people were arrested on February 7, 2021. There was Judge Dabrésil, as well as three of his cousins, his driver, and two of his security agents; there were the Gauthier sisters, and Marie Antoinette’s husband, the agronomist Louis Buteau; two employees of the Petit Bois complex; two small-time opposition politicians; two members of the Haitian police, both of whom worked for the prison division; Chantal Saintime, who had signed the lease agreement; and, finally, her 21-year-old daughter, Hija Djenicka Philippe, whom she had had with Philippe Markington. The police seized seven guns, most of which apparently belonged to the police officers and security guards staying there.

The whole Petit Bois affair was interpreted by supporters of Moïse as a bloody coup attempt that proved that the president’s opponents were hell bent on overthrowing or even killing him, and, on the other hand, as a sordid set-up, a plot to entrap political opponents that showed the extent to which the president would go to hang on to power. A meme began flying around on social media with people posting regular household items with the caption: "coup d’etat." “You don’t lead a coup with four old rifles,” an opposition leader declared.

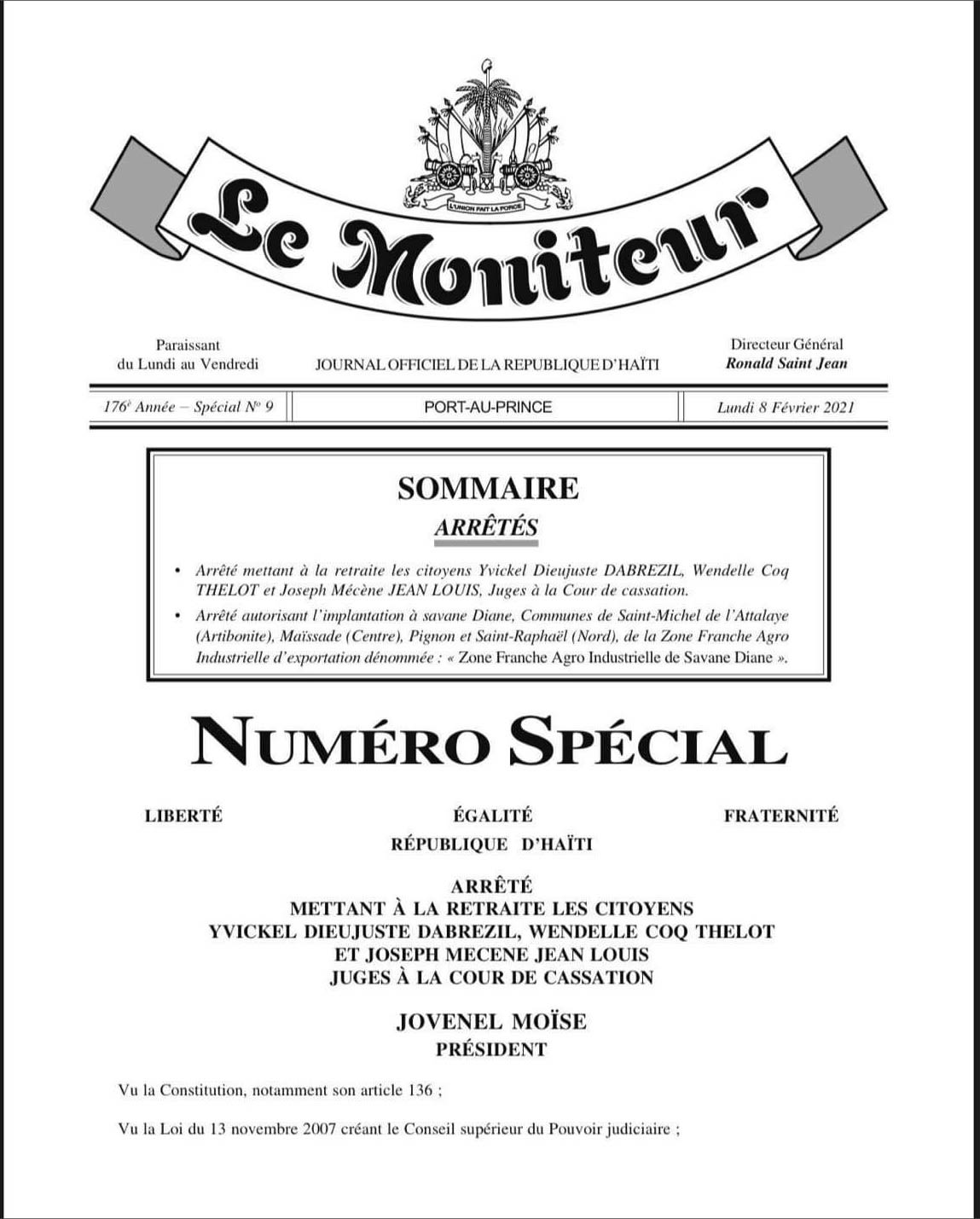

Those arrested were accused of participating in a “conspiracy against the internal security of the state,” a legal term that had only really ever been applied by the Duvalier dictatorship. And, to many in Haiti, that’s what things were beginning to look like. Moïse had been ruling by decree for over a year, the terms of parliament having expired in January 2020. After February 7, he fired and replaced three Supreme Court judges — Coq Thélot, Dabresil, and a third judge, Joseph Mécène Jean-Louis, whom some in the opposition had recognized as president. Moïse had consolidated power in the executive, created a new intelligence agency, and was openly talking about reforming the constitution through a national referendum. The last time that had happened was, once again, under Duvalier, when he declared himself president for life. Many expected the government to use the Petit Bois affair as the basis for a widespread crackdown on political opponents.

Le Moniteur from February 8, 2021 where Moïse decrees the retirement of three supreme court judges.

Le Moniteur from February 8, 2021 where Moïse decrees the retirement of three supreme court judges.

But the investigation into Petit Bois went nowhere. Judge Dabresil was released from jail within a few days, his arrest ruled illegal. By the end of March, 16 of the 17 others were also released. It was quite clear that none of them had been calling the shots. They had been played, convinced by a smooth-talker claiming to have the support of the United States government. Even the president’s own top security officers were in on it, they had been led to believe. None of those individuals arrested were planning a bloody coup d’etat. There was no military force ready to storm the palace and seize power. They did, however, truly seem to believe that a peaceful transfer of power was not only possible but necessary for Haiti's future. Of course, they were wrong, and they ended up taking the fall. But the question remained: who was pulling the strings behind it all?

If Whitman was the ringleader, and Whitman was actually Markington, was the entire thing organized out of a jail cell in the Haitian capital? And if so, certainly it couldn’t have been done alone. Markington has a reputation as a talker, but it is hard to imagine that he had dreamed up this entire plot on his own. He had spent months on the phone from prison using multiple numbers. At the very least, someone would have had to pay for all those cell phone minutes.

Instead of the judicial police taking the lead in the investigation, Moïse gave the task to his own security forces, mainly to Dimitri Herard and Jean Laguel Civil, both of whom had been actively engaged with those arrested — and with Markington — since at least November 2020. If the Petit Bois plan ever represented a real threat to the president, it would only have been because both Herard and Civil were part of it.

Five months to the day after Moïse praised his security chiefs for disrupting this coup plot, he was assassinated, shot 12 times in his bedroom. Both Herard and Civil are now in jail, accused of, at the very least, negligence in allowing the president’s assassination to take place. According to the preliminary investigation conducted by the Haitian police, Civil allegedly had at least $80,000 to distribute to palace security the day of the attack while Herard provided arms, ammunition, and other supplies to the Colombian mercenaries accused of carrying out the assassination. Both have denied the allegations.

After the assassination, it was impossible not to think back to Petit Bois. What had really happened? Had Herard and Civil actually been serious about turning on the president? Why didn't they go through with it? Who was behind Markington? I was reminded of something a source had told me just days after the Petit Bois arrests. They had told me that there wasn’t simply one plan. No, they explained, there was also a plan being organized in Delmas 60, and even another one coming out of the Dominican Republic. “All of them are being manipulated by the same people,” the source had said.

Christian Sanon had been arrested at a home in Delmas 60 two days after the assassination. He hadn’t fled. He didn’t go into hiding. He was a sitting duck, just like those arrested in Petit Bois. Had Sanon been manipulated by the same people?

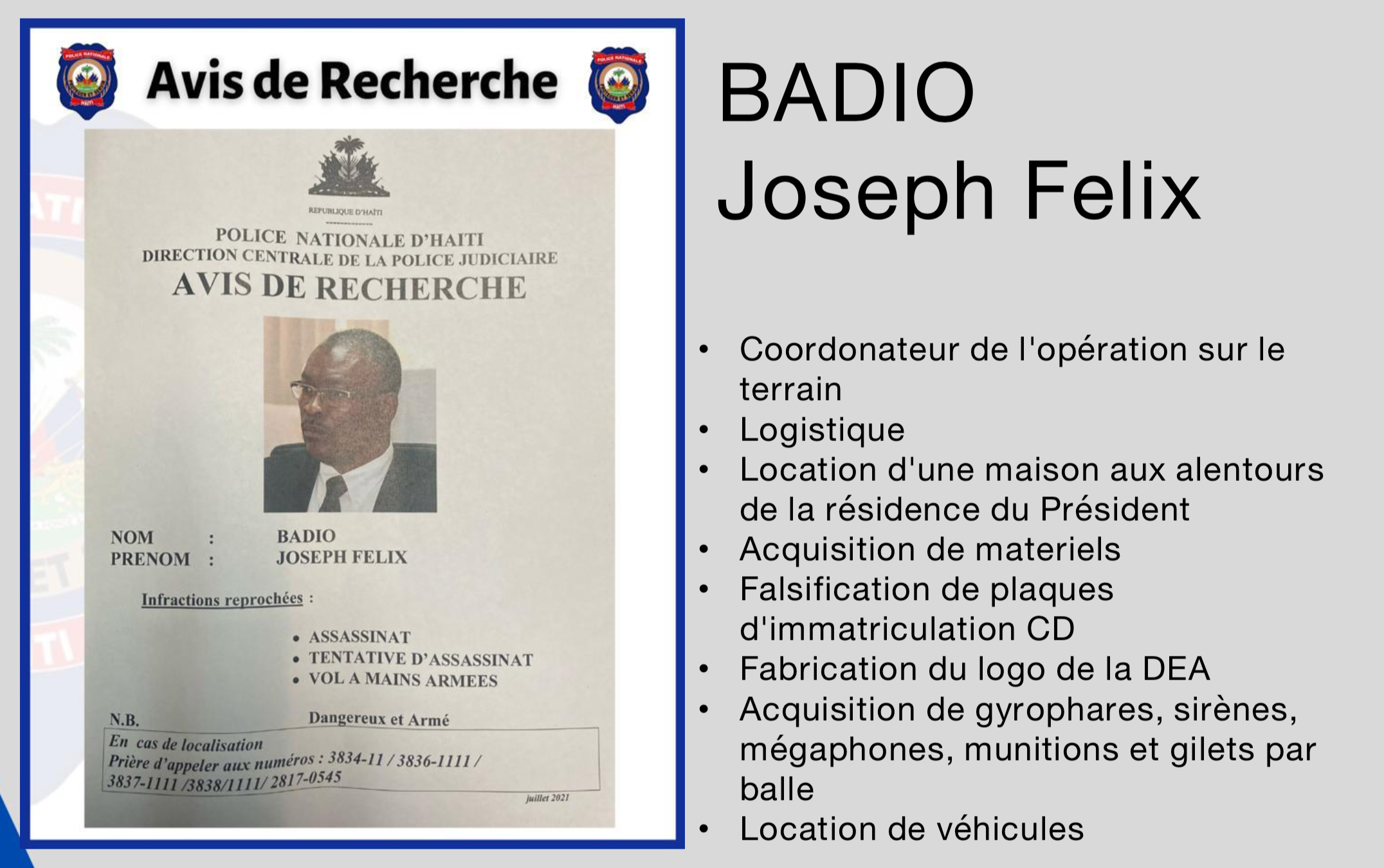

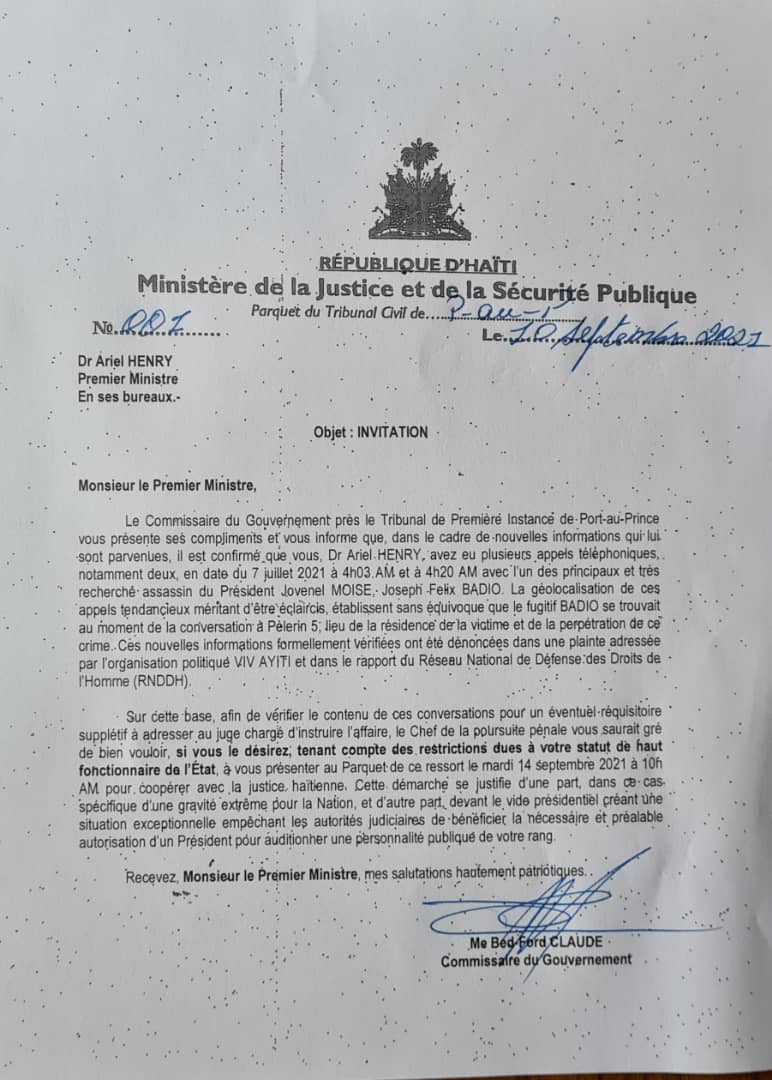

Slide from Haitian National Police presentation showing wanted poster for Joseph Felix Badio.

Slide from Haitian National Police presentation showing wanted poster for Joseph Felix Badio.

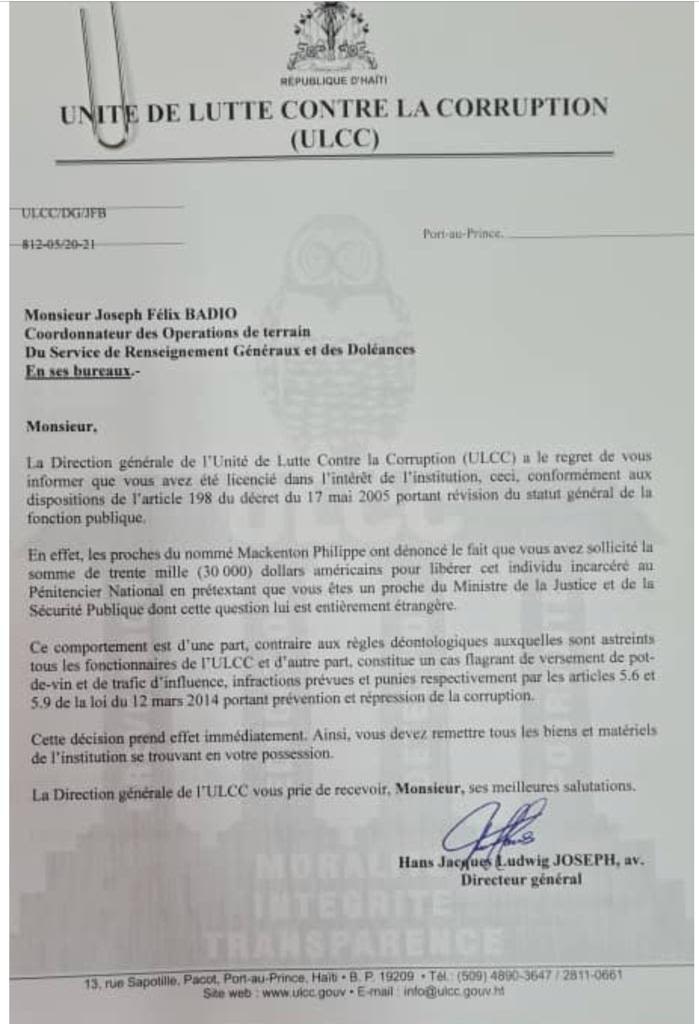

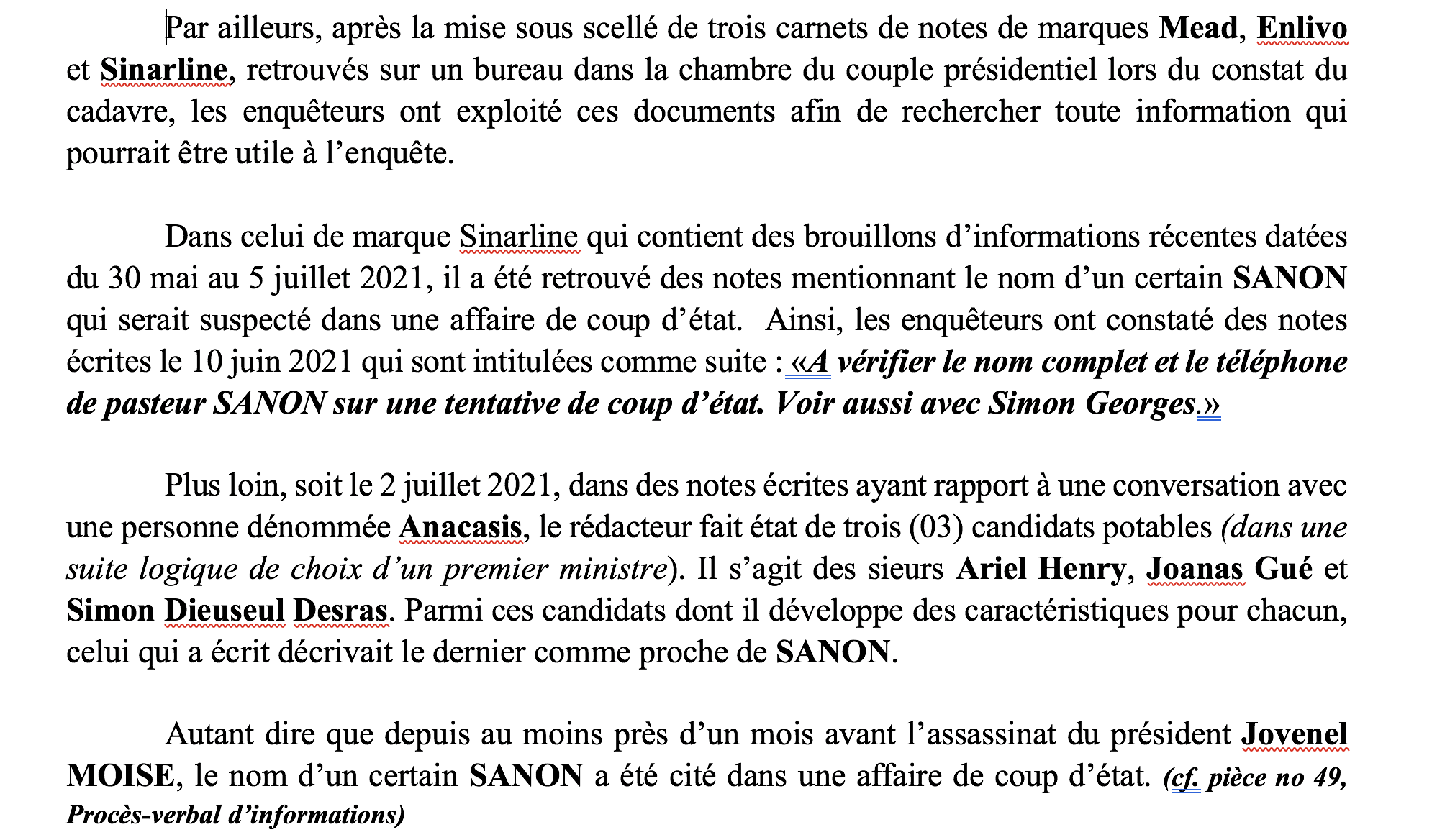

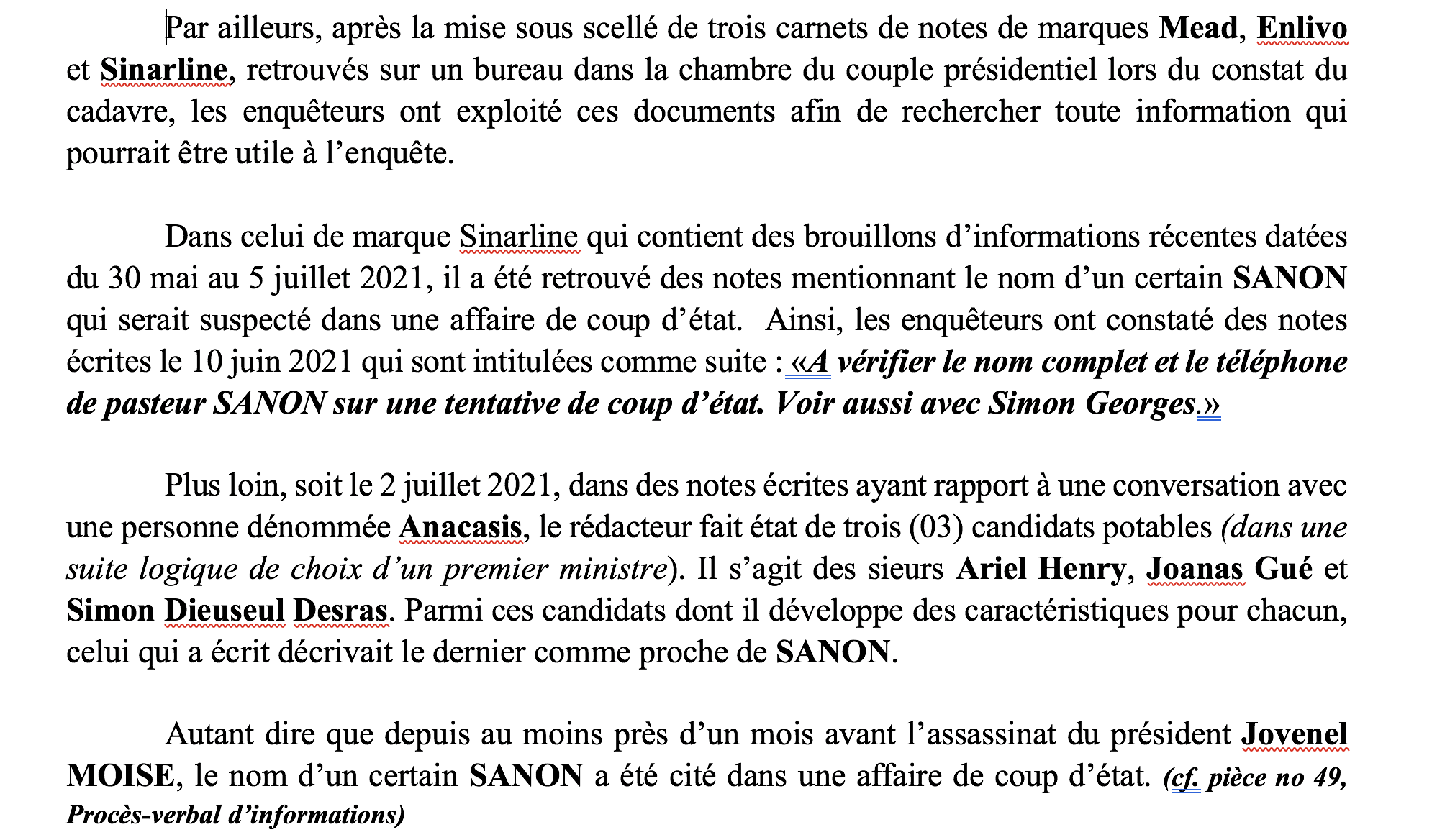

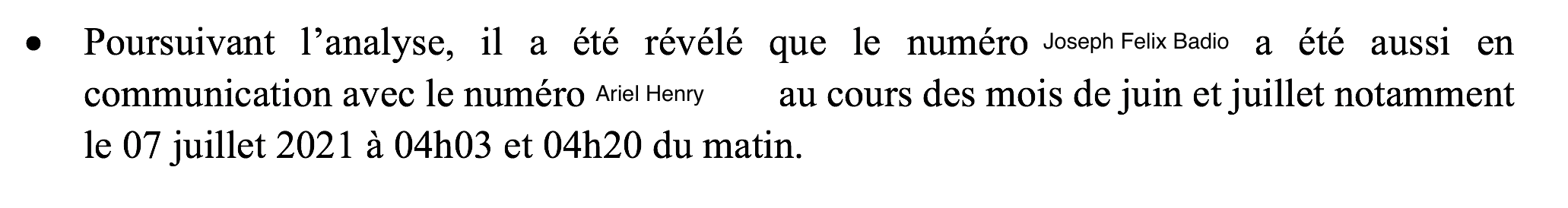

A week after the assassination, the Haitian police issued an arrest warrant for Joseph Felix Badio, a longtime mid-level official at the Ministry of Justice who more recently had been working for the country’s anti-corruption unit, the ULCC. Badio, a tall, slender figure with a faint mustache, is considered a key figure in the plot. The Colombian police reported that it was Badio (and not Sanon) who changed the mission and ordered the Colombian mercenaries to take out the president rather than attempt to arrest him. Some of those detained apparently told investigators that it had been Badio who, the night of the assassination, gave word that the operation was a go. He had even rented an apartment close to the president’s home and had been keeping tabs on him for many months. The Haitian police said that Badio had been fired from his position at the ULCC in May, but failed to provide any specific reason.

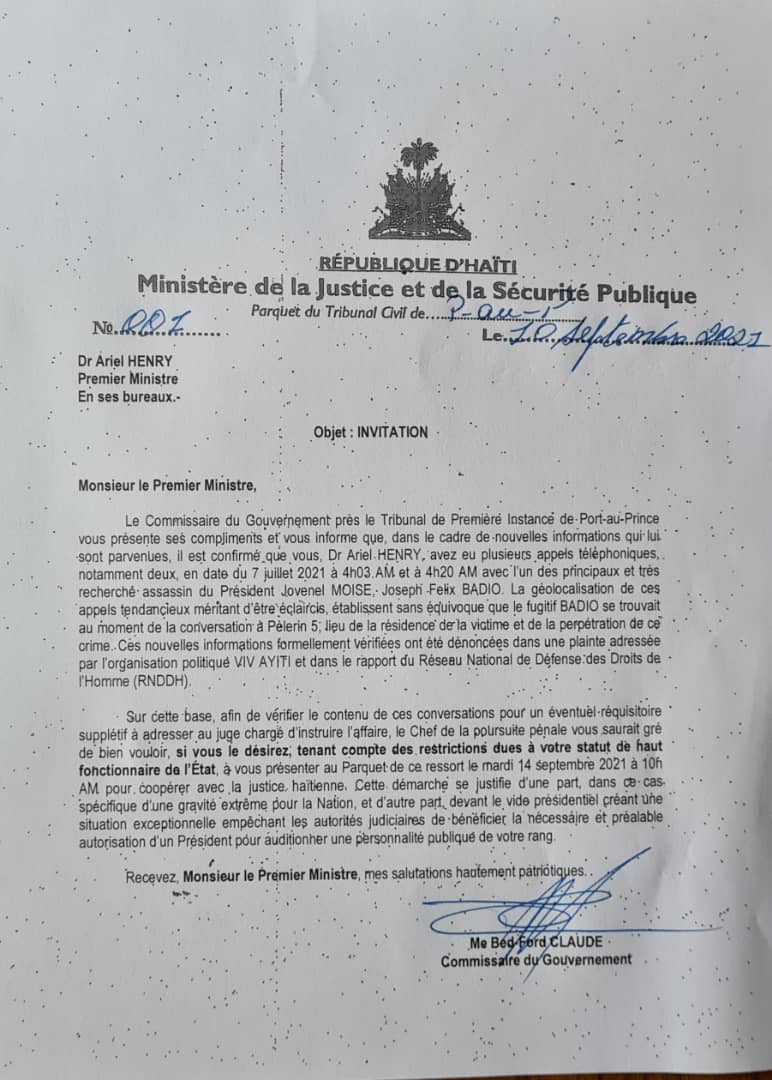

Could his firing provide answers? A few weeks later, a journalist sent me a letter from ULCC that explained why Badio had been fired. According to that document, the authenticity of which was confirmed by the head of the ULCC, it resulted from of an accusation that Badio had solicited a $30,000 bribe from an inmate with a promise to get them out of jail.

Document from anti-corruption unit providing the reason for Badio's dismissal: an allegation that he had solicited a $30,000 bribe in exchange for releasing a "Mackenton Philippe" from jail.

Document from anti-corruption unit providing the reason for Badio's dismissal: an allegation that he had solicited a $30,000 bribe in exchange for releasing a "Mackenton Philippe" from jail.

According to that document, the inmate was "Mackenton Philippe," a different spelling of Markington, the man impersonating Whitman from his jail cell, the man who had facilitated a $30,000 money transfer from Mexico. According to sources consulted as part of this investigation, Badio is a close contact of John Joseph Ferert Douyon, the individual who received the $30,000 transfer from Mexico.

It wasn’t the only connection. Badio’s name had come up before, the morning of February 7. “I’m hearing the name of [Joseph Felix] Badio…who led them to believe State Department was supporting the idea,” a contact messaged me that day. Multiple sources who have known Badio for years said he had long claimed ties to the FBI and DEA, though they doubted it was true. After decades working in government, he was extremely well connected across the political spectrum. The Miami Herald later reported that Moïse had even been considering Badio for a high-level position within his government.

Was it Badio that manipulated Markington? Did that explain the $30,000 transfer from Mexico? Did Badio put him up to it all with a promise to help get him out of jail? Badio had been in direct communication with Markington since at least early August 2020, before Markington had even made a connection with the Gauthiers or anyone else eventually arrested in Petit Bois. Badio’s name, however, never came up publicly at the time.

Markington’s relationship to those arrested at Petit Bois, or to Badio, would have been an easy connection for Haitian police investigators to make. A cursory review of phone records would identify his role in the affair. I can confirm that Haitian police had that information. Further, Markington himself made multiple calls to the police the morning of the arrests from a cell phone registered in his name. The other individual who had seemingly been involved from day one was Mario Beauvoir, the former government commissioner who had skipped town the day of the arrests. The police never even issued an arrest warrant for him.

It was as if the authorities had no intention of actually investigating. Why? And, if a real investigation had occurred, would the president have ended up dead?

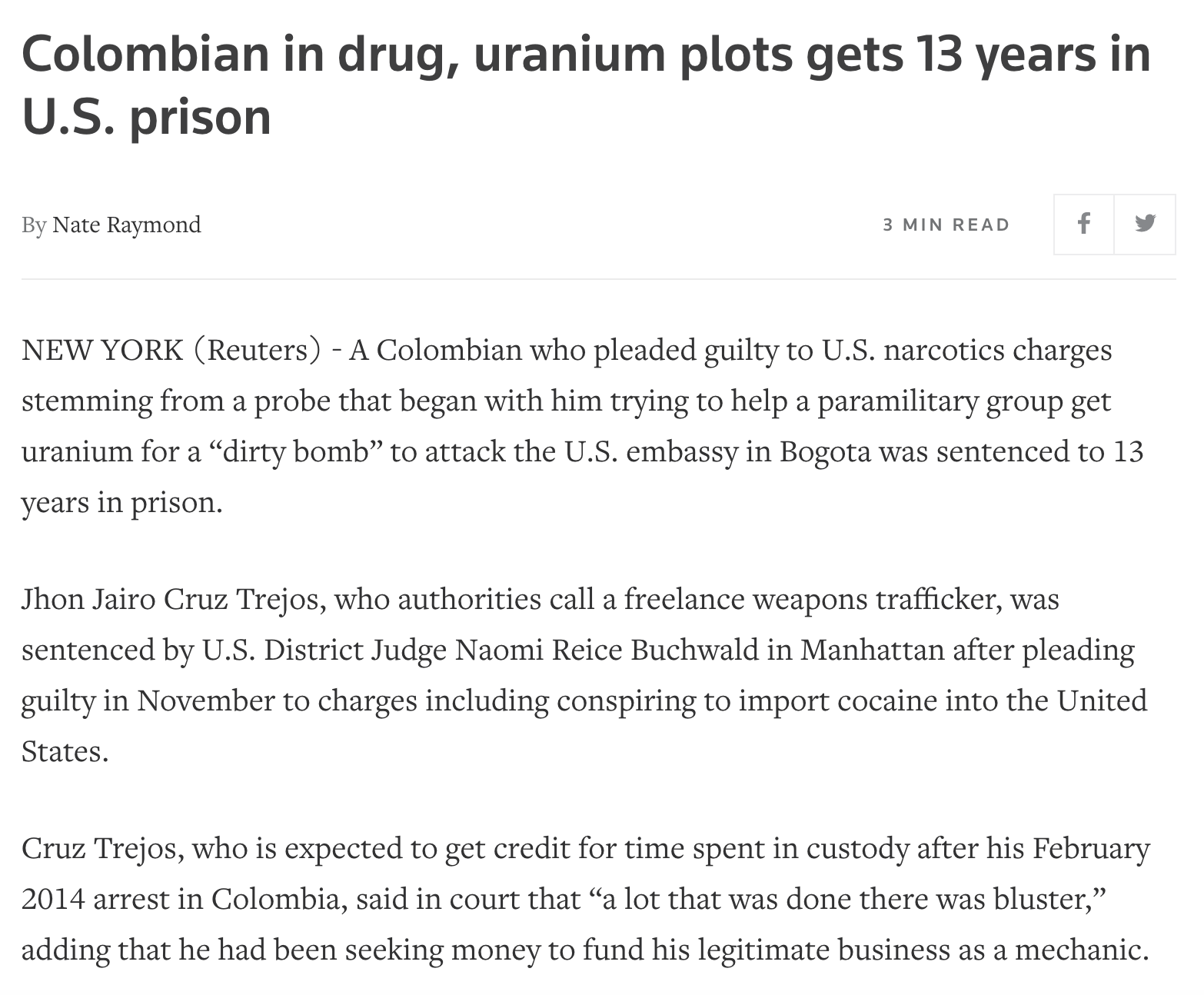

April 4, 2016 Reuters article detailing the drug and uranium scheme.

April 4, 2016 Reuters article detailing the drug and uranium scheme.

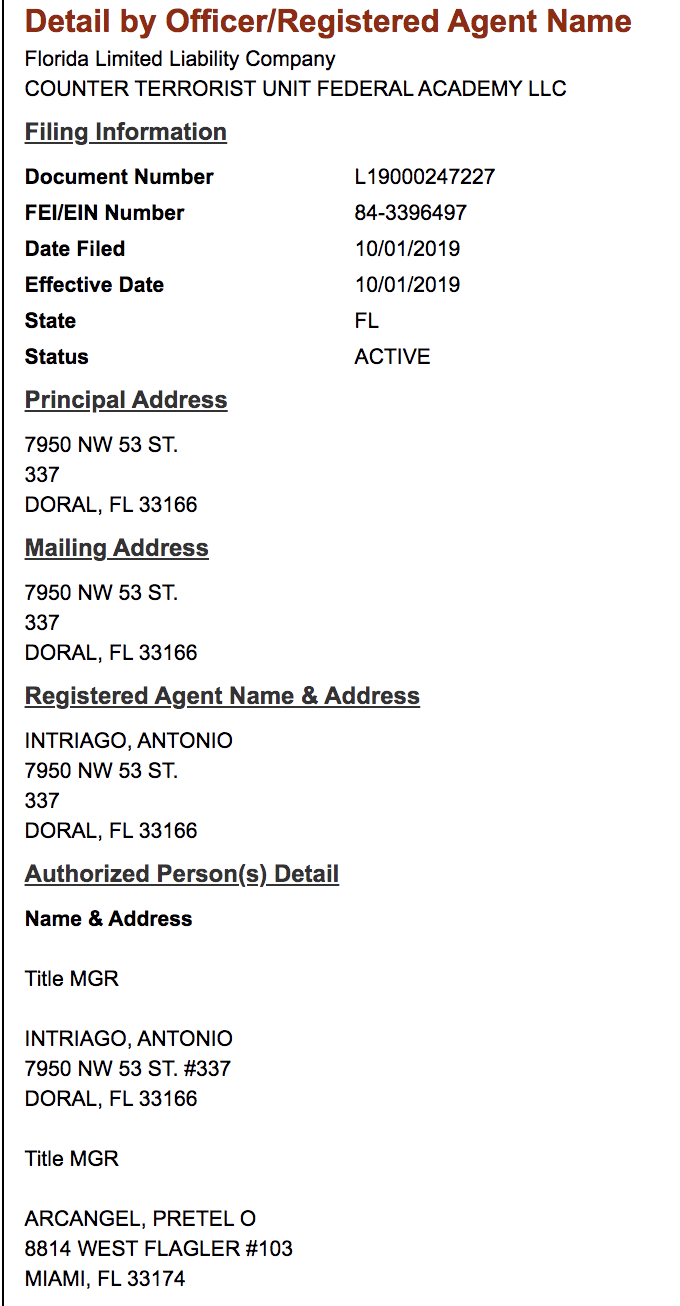

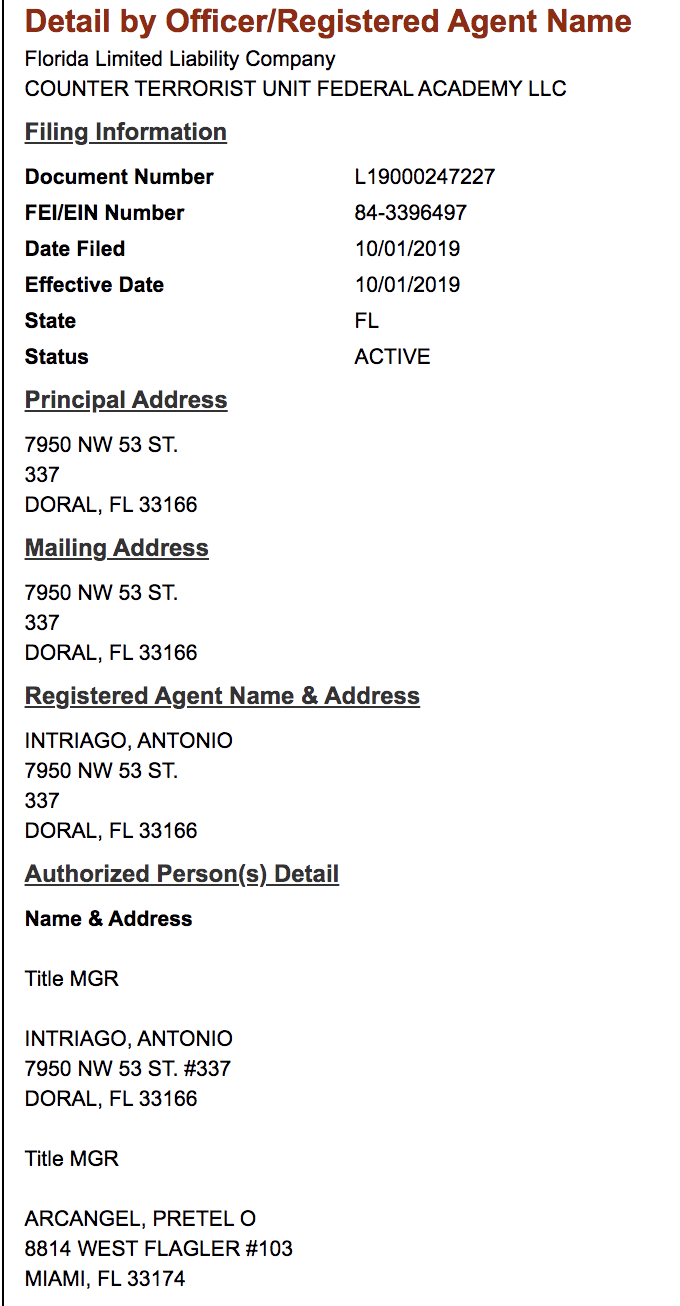

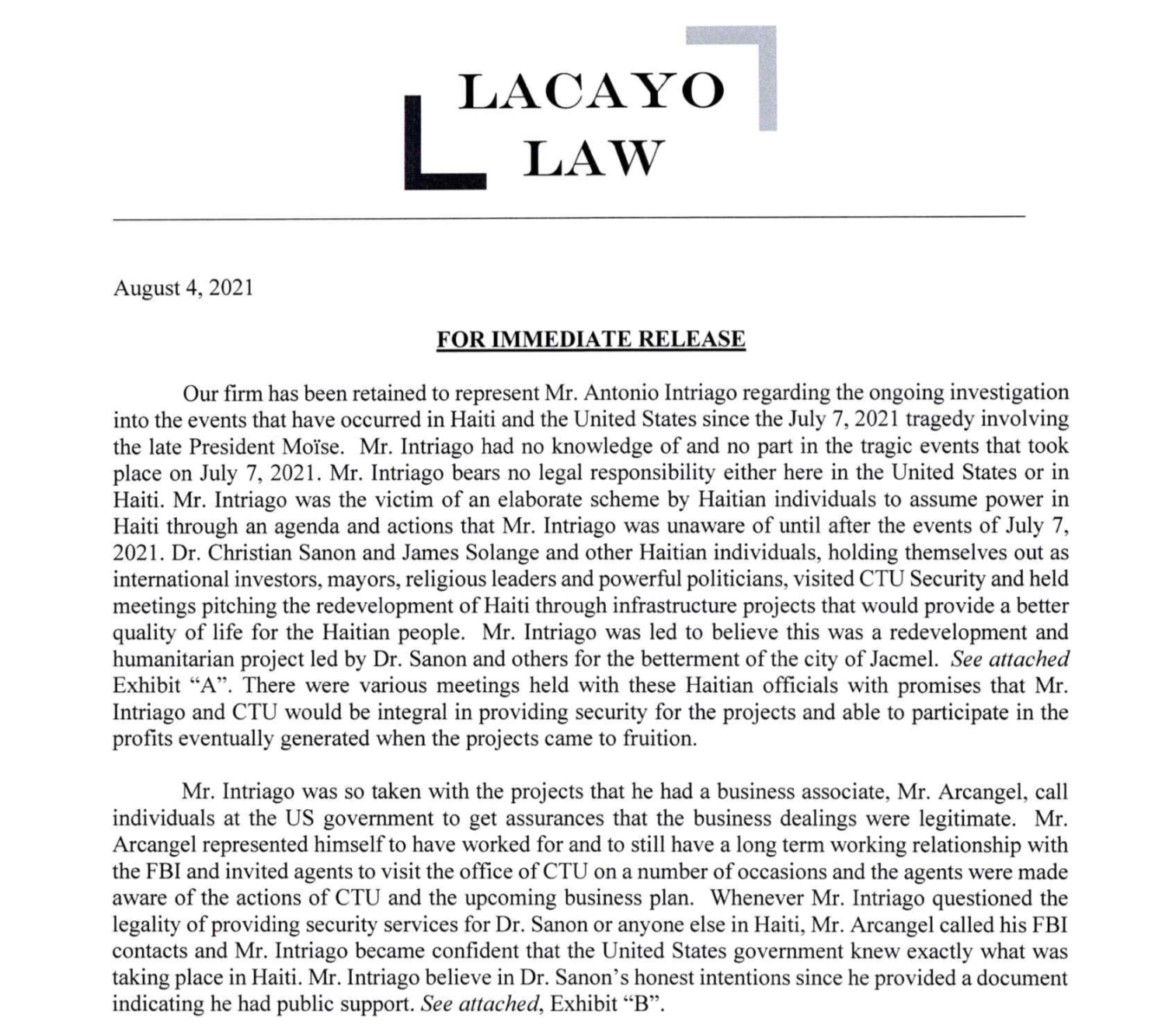

Florida business registration for Counter Terrorism Unit Federal Academy LLC. The company was created in 2019 with two managers listed: Antonio Intriago and Pretel O. Arcangel. Intriago, through his lawyers, claims that Pretel had a working relationship with the FBI.

Florida business registration for Counter Terrorism Unit Federal Academy LLC. The company was created in 2019 with two managers listed: Antonio Intriago and Pretel O. Arcangel. Intriago, through his lawyers, claims that Pretel had a working relationship with the FBI.

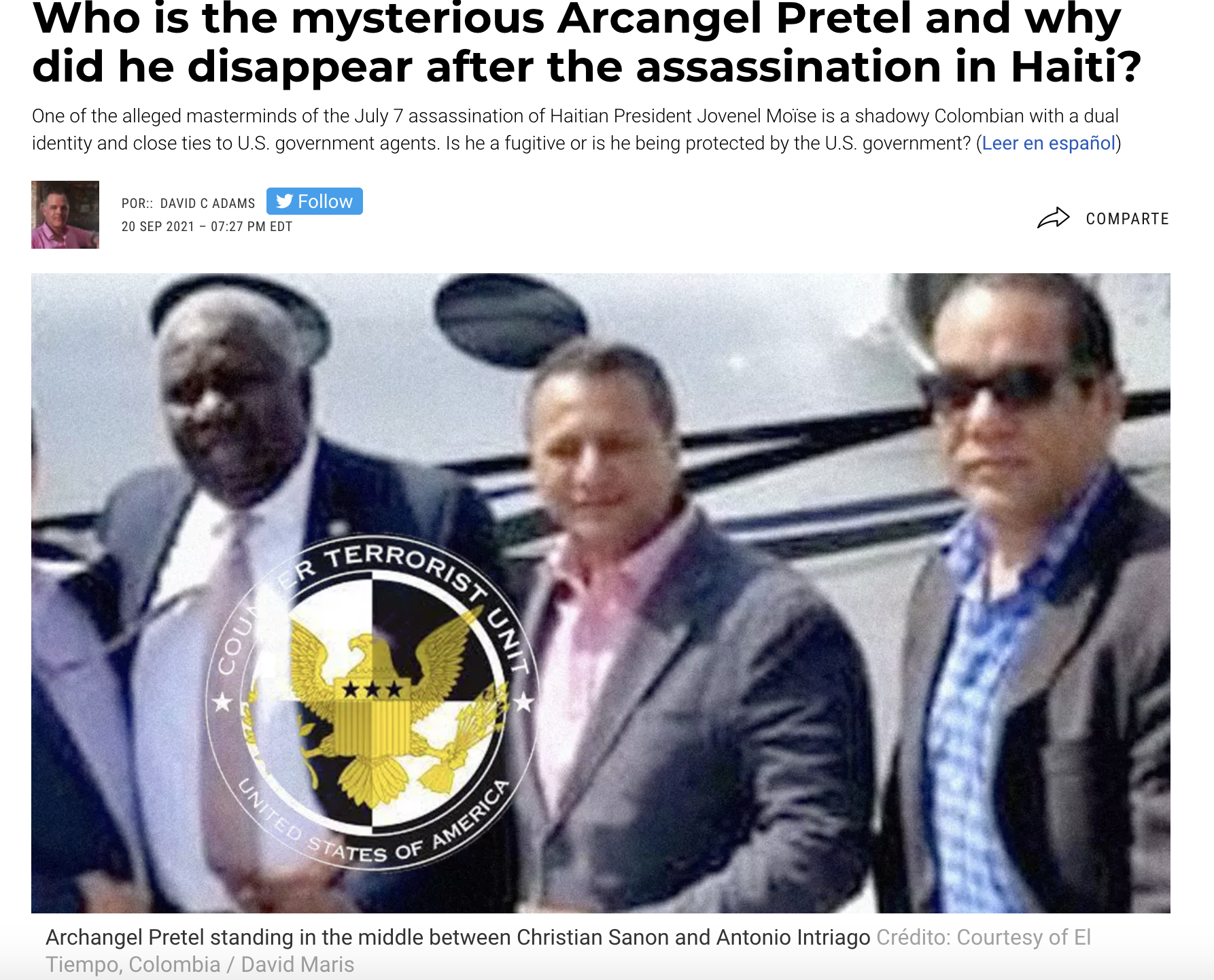

September 20, 2021 Univision article about Arcangel Pretel.

September 20, 2021 Univision article about Arcangel Pretel.

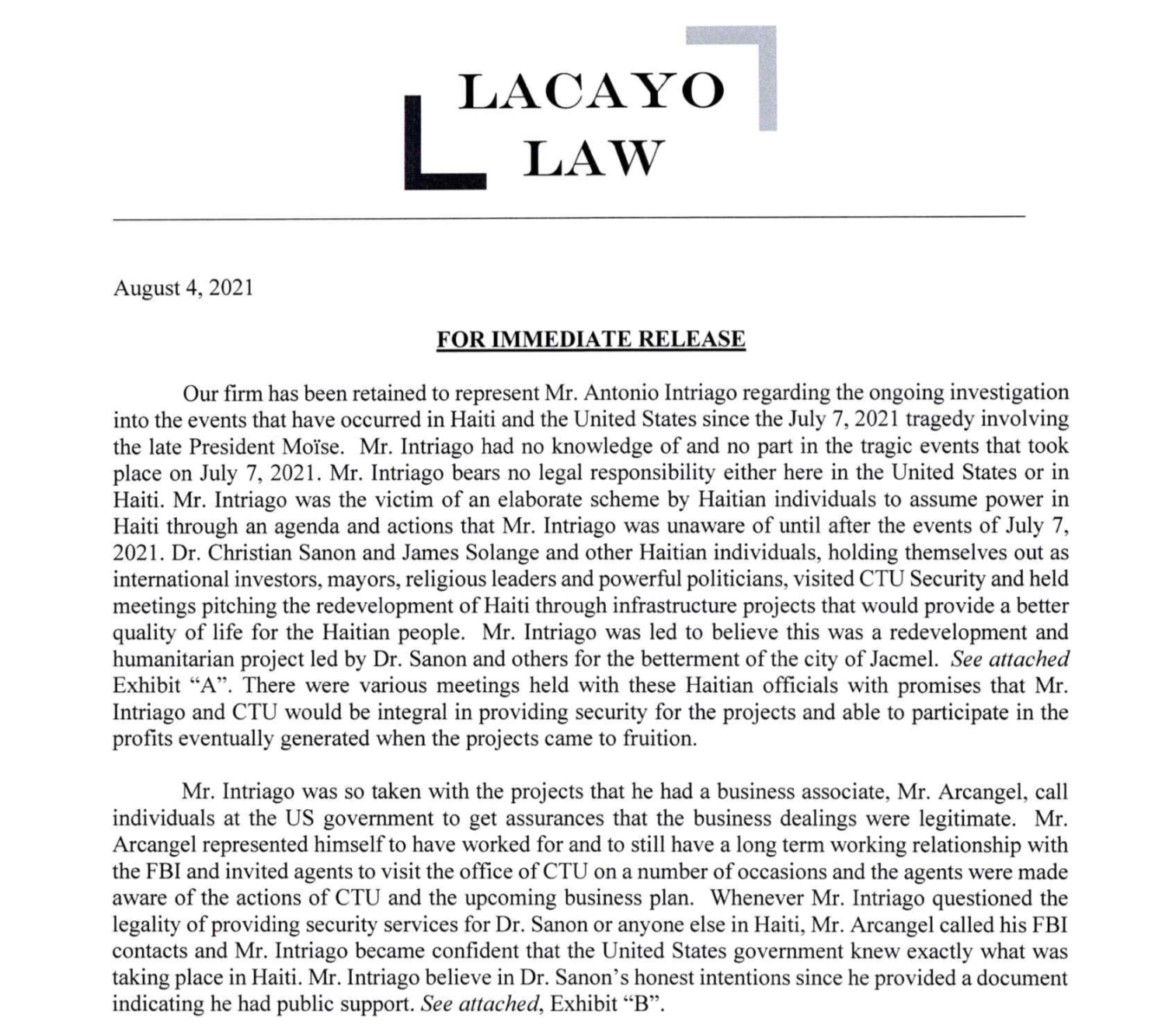

Letter from lawyer of CTU Security alleging that Arcángel Pretel presented himself as having a longstanding relationship with the FBI.

Letter from lawyer of CTU Security alleging that Arcángel Pretel presented himself as having a longstanding relationship with the FBI.

Photo of one of the Colombian former soldiers in the Dominican Republic, posted on Facebook.

Photo of one of the Colombian former soldiers in the Dominican Republic, posted on Facebook.

Photo of one of the Colombian former soldiers in the Dominican Republic posted on Facebook.

Photo of one of the Colombian former soldiers in the Dominican Republic posted on Facebook.

Photo of one of the Colombian former soldiers in the Dominican Republic posted on Facebook.

Photo of one of the Colombian former soldiers in the Dominican Republic posted on Facebook.

Four of the retired Colombian military officers arrested in Haiti can be seen cooking at the location they stayed in Port-au-Prince.

Four of the retired Colombian military officers arrested in Haiti can be seen cooking at the location they stayed in Port-au-Prince.

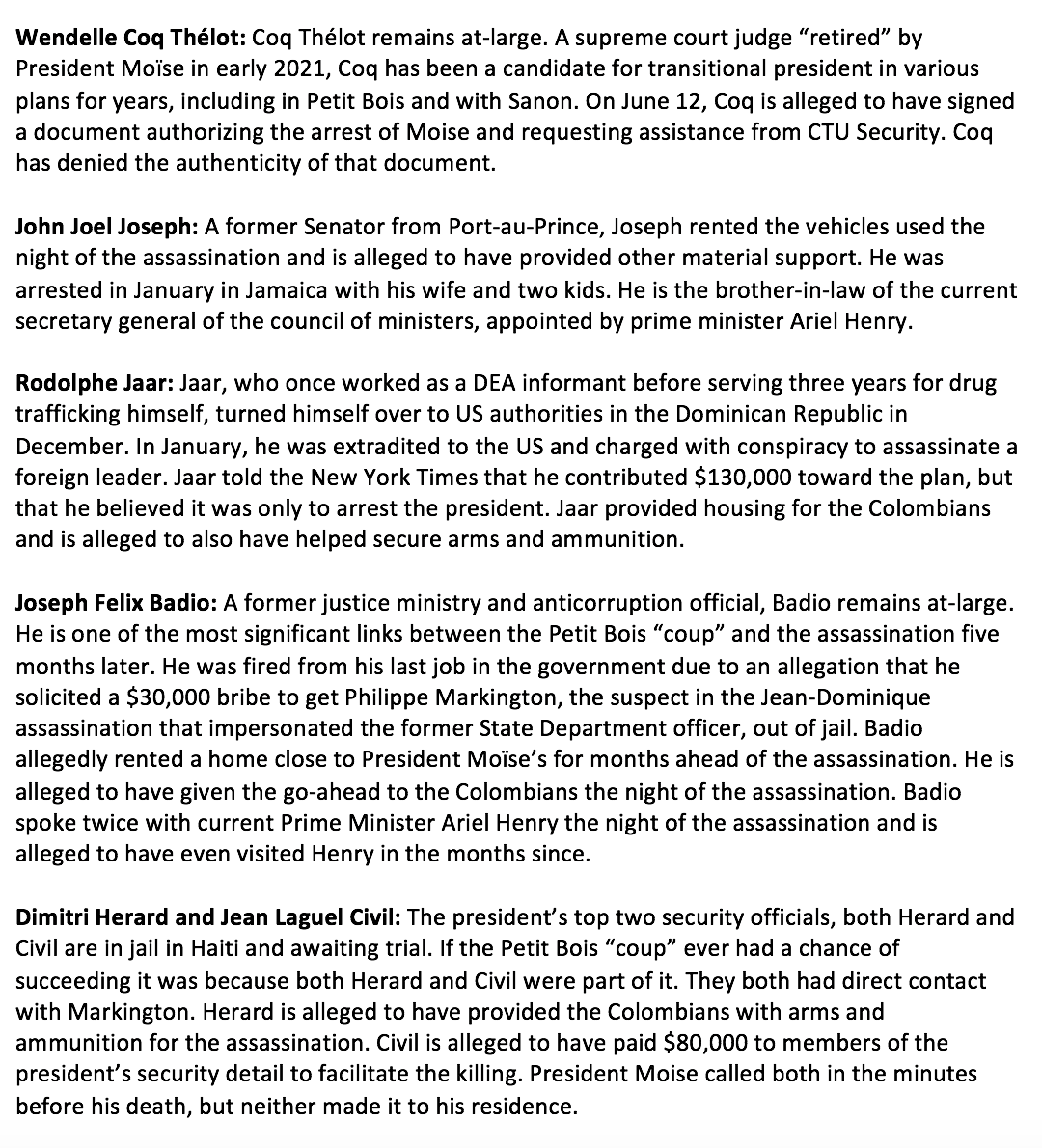

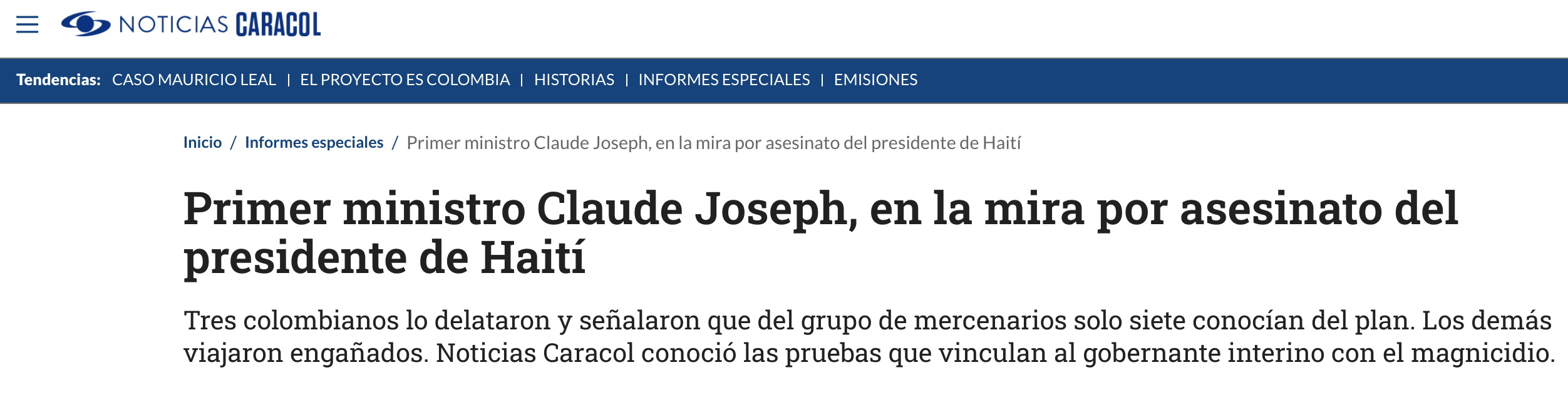

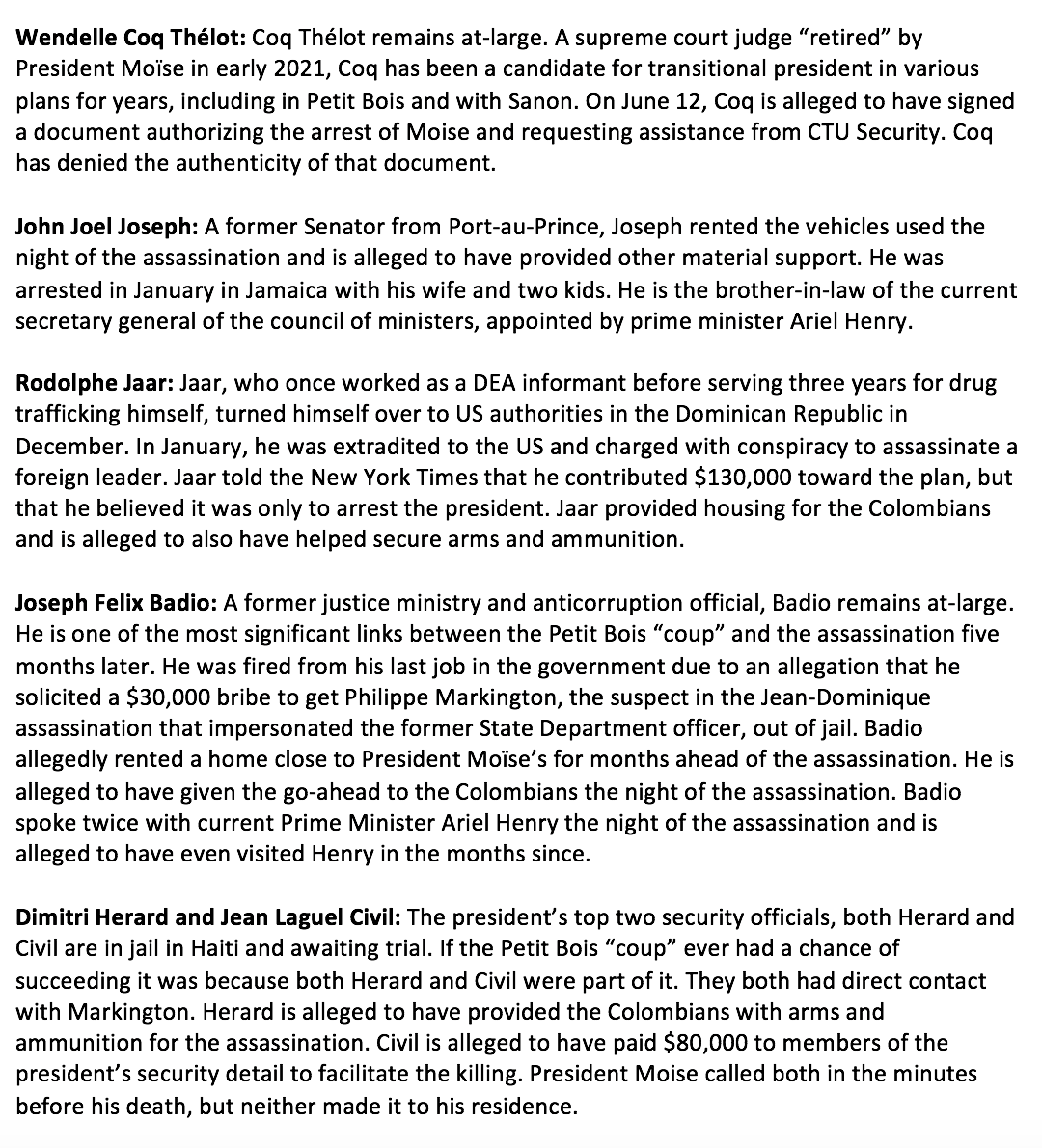

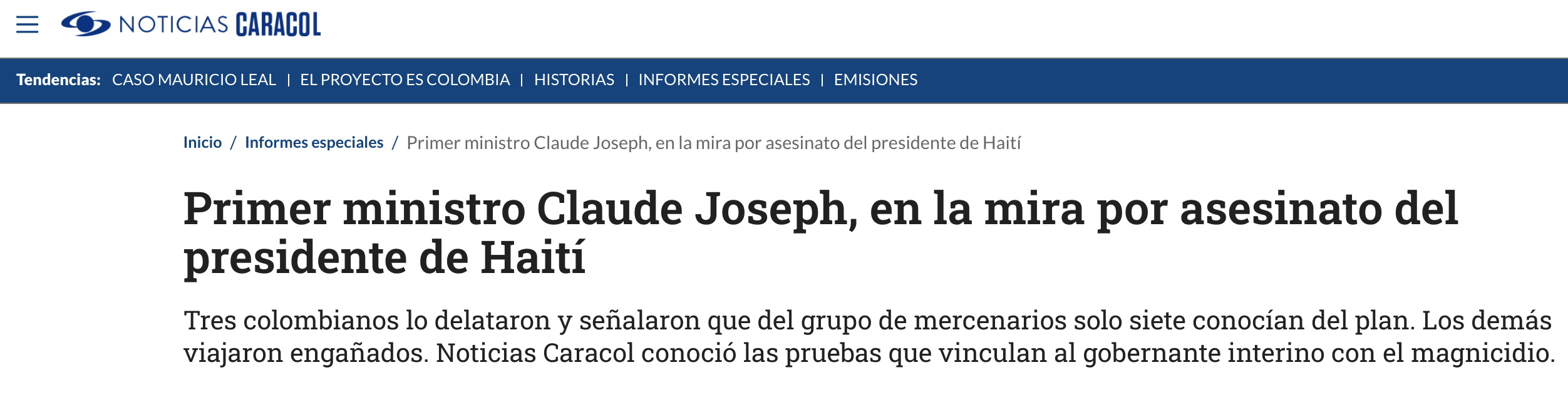

THE PLOT