Our Boss Will Call Your Boss

On February 17, Haitian police arrested seven Blackwater-like security contractors a few blocks from the country’s Central Bank. They claimed to be on a government mission, and had a cache of weapons. Four days later the US “rescued” them. What happened?

An investigation by:

At 4:59 a.m. on Saturday, February 16, a private plane registered to a South Florida charter company touched down at the Toussaint Louverture International Airport in Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

The plane landed in the midst of a worsening economic downturn, metastasizing corruption scandal, and a deadly political crisis. For the previous nine days, large parts of the country had been shut down by street protests and barricades pushing for the president’s resignation.

The plane arrived direct from Baltimore/Washington International Airport (BWI), where it departed just after 2:00 a.m. On the plane were a handful of American contractors, apparently including highly trained former military officers with experience in Iraq and Afghanistan. Once in Haiti, at least some of the contractors reportedly bypassed immigration, and, police officials believe, were met at the airport by two local businessmen with close ties to the ruling party, Josue Leconte and Gesner Champagne. Also present, according to those same sources, was Fritz Jean-Louis, a former government official.

A Hawker 800 mid-size twinjet corporate aircraft, similar to the one used.

A Hawker 800 mid-size twinjet corporate aircraft, similar to the one used.

The next day, a group of the contractors attempted to enter the Central Bank, the Banque Republique d’Haiti. A security guard on site denied access and alerted high-level bank officials. Sources with knowledge of the situation confirmed that Leconte and Jean-Louis, two of the men who met the contractors at the airport, had been in contact with the Central Bank governor over the previous two weeks. But the contractors apparently never entered the bank, and someone tipped off the police.

That afternoon, police detained seven contractors and their driver — five Americans, two Serbians, and a Haitian national — just a few blocks from the bank. The contractors, at least some of whom had arrived only 36 hours prior on the flight from Baltimore, were driving in unmarked vehicles. Inside, agents found six semi-automatic rifles, six pistols, two drones, satellite phones, and other tactical equipment.

The group was on a government mission, they told the police. “Their boss will call our boss,” one of the officers later recalled being told.

A demonstration in November calling for accountability in the government's handling of some $2 billion in Petrocaribe spending.

A demonstration in November calling for accountability in the government's handling of some $2 billion in Petrocaribe spending.

That evening, the Haitian minister of justice personally intervened for the contractors’ release, according to local reports, independently confirmed. One of the Haitian president’s advisors also made a call. Fritz Jean-Louis, who has reportedly fled the country, told police it was part of a Central Bank security assessment. The bank denied any involvement. The contractors remained detained.

Nobody took responsibility for bringing these contractors to Haiti. The US Embassy provided consular services, but denied any knowledge of the group’s purpose in the country.

On the afternoon of February 20, after nearly three days of nonstop speculation in the local and international press that seemed to raise more questions than answers, the group was quietly released into US custody. That night, video emerged of the group as US embassy personnel escorted them through the American Airlines ticket counter. None appeared to be in handcuffs.

They flew commercial in a mostly empty plane to Miami where they were met by US law enforcement, though it remains unclear from what federal agency. The next day, citing federal sources, the Miami Herald reported the contractors would not face charges. The Haitian president and prime minister both denied any knowledge of the situation. The US government has not made any public remarks on the case.

The only public explanation provided by any of those involved came in the form of an Instagram post (since deleted) by one of the returned Americans. He claimed that “people who are directly connected to the current [Haitian] president” had hired them “to do security work.” But weeks later, much of what happened during the roughly 36 hours before the group was detained remains shrouded in secrecy.

Though significant details are still unknown, the following account — based on existing reports, interviews with sources close to the situation, government documents, flight and other records relating to the case — raises significant questions for authorities in both Haiti and the United States.

Why was the group driving in unmarked cars, with unregistered weapons, and without immigration stamps in their passports? What had they been hired to do? And on whose behalf? Are there other contractors still in Haiti? What did Central Bank officials know, and when did they know it? Was the bank the target of the mission, or just the site of its downfall? And who is covering the whole affair up? Why did the US government break with widely respected diplomatic procedures and international laws? Why are they not facing any charges in Haiti or the US? And what does the whole case have to do with the ongoing political crisis, and with the US role in Haiti today?

In the following report, Haiti: Relief and Reconstruction Watch (HRRW) will provide the most complete account of the contractors’ detention, what they had done in Haiti before their detention, and the political and diplomatic discussions that surrounded the event. Over the course of just a few days, the case took on political significance much greater than the detention and release of the contractors. The chain of events initiated by the detention revealed the weakness of the nation’s justice system and the precariousness of the current Haitian administration; it exposed the close ties between criminal networks and the ruling party; and casts doubt on the idea that this was a simple security operation gone wrong.

Continue scrolling for the full investigation.

For major findings and information on the individuals involved, as well as detailed looks at the contractors themselves, the American-owned company at the center of the scandal, and the plane that brought some of the contractors to Haiti, see the Appendix.

THE “MERCENAIRES”

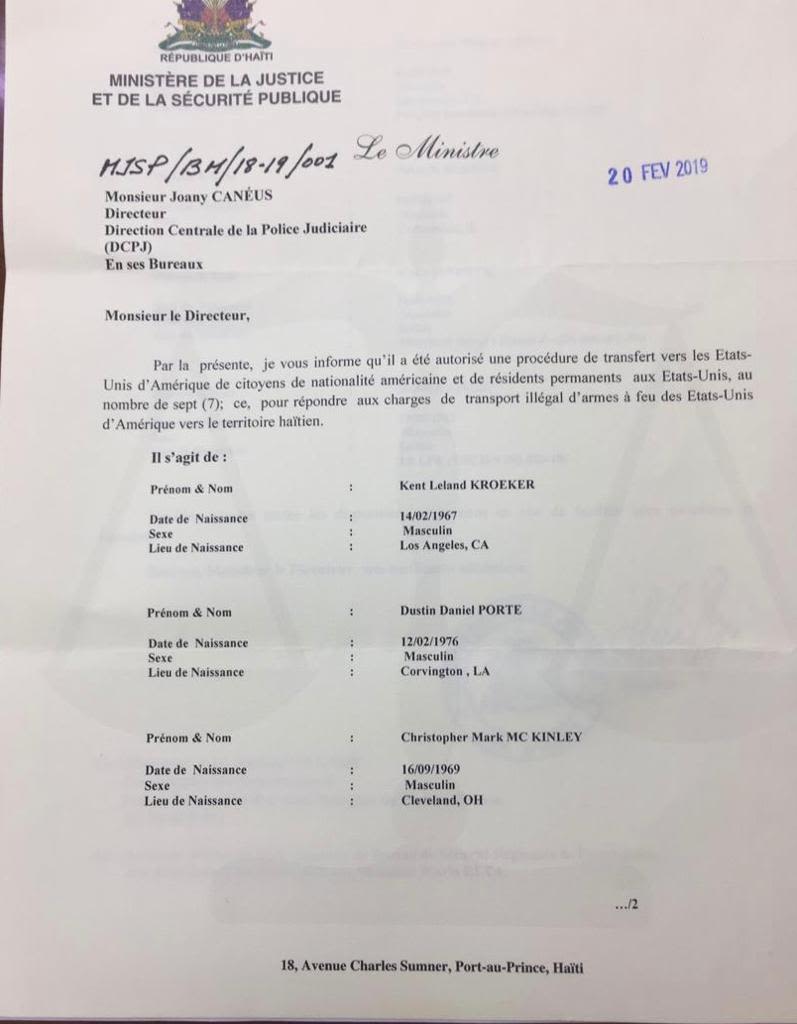

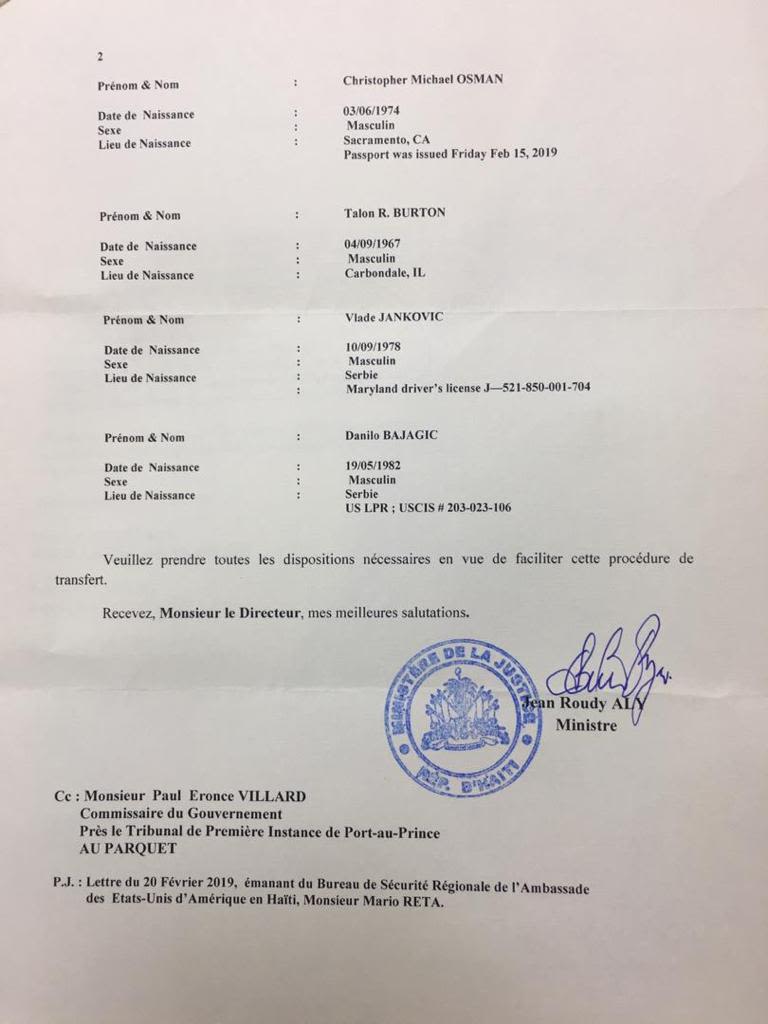

Despite the sensitivity of the case, the identities of those detained were widely known within hours: Dustin Porte, Talon Burton, Christopher Osman, Kent Kroeker, Chris Mark McKinley, Danilo Bajagic, Vlade Jankovic, and Michael Estera.

Two are former navy SEALs, one a former marine. Another worked as diplomatic security in Afghanistan. Outside of Estera, the Haitian national, six of the seven detained have public links to private security companies in the US, from Maryland to Southern California. In Haiti, they’ve simply become “the Mercenaires.”

On February 22, Christopher Osman posted a picture with his wife on Instagram. The message accompanying that post has been the only public comment from any of the contractors involved. The post has since been deleted. At least two companies have publicly denied any role in the operation.

“Sometimes life is stranger than fiction and filled with crazy adventures,” Osman wrote, “Its [sic] now known that I do security work and have done it for years.” He claimed that’s what the team had been doing in Haiti — and “people who are directly connected to the current President” had hired them. Osman blamed a political fight between the president and prime minister for the ordeal, and thanked the US government, specifically the ambassador, for their “rescue.”

Relatively little is known about those detained, or why such a disparate group was brought together. But, it turns out, for some of those detained, this wasn’t their first trip to Haiti. At least one had been brought to Haiti by a wealthy businessman just seven months earlier, at the onset of Haiti’s current political crisis.

In early July, the government announced that fuel prices would increase by up to 50 percent. It was running out of money, and the measure was part of a list of reforms needed to secure an International Monetary Fund rescue package.

Protests, some of which targeted private businesses, erupted across Port-au-Prince and continued even after the government rescinded the decree. The airport was closed. Among the businesses damaged in the protests were the Best Western hotel and MSC Trading. Both are owned by one of Haiti’s most well-known elite families, the Handals.

After the unrest, Chris Handal, a co-owner of the hotel and MSC, brought in foreign security contractors to assess the situation. According to private sector sources, that group included Kent Kroeker. Handal declined to comment for this report.

The presence of foreign security contractors in Haiti is nothing new. During times of unrest, businessmen have often brought in such teams. The Steele Foundation was on a “State Department-approved” security contract with the Haitian government for years. In 2004, Steele agents were present as former president Jean-Bertrand Aristide faced an internal revolt, including from within his own security forces, and was flown out of the country — against his will, he later claimed — on a leased plane that had been used by the United States for extraordinary renditions.

But if the contractors were simply in Haiti to provide routine security assessment or protection, it is their connections and actions in Haiti that raise significant questions about the nature of their mission.

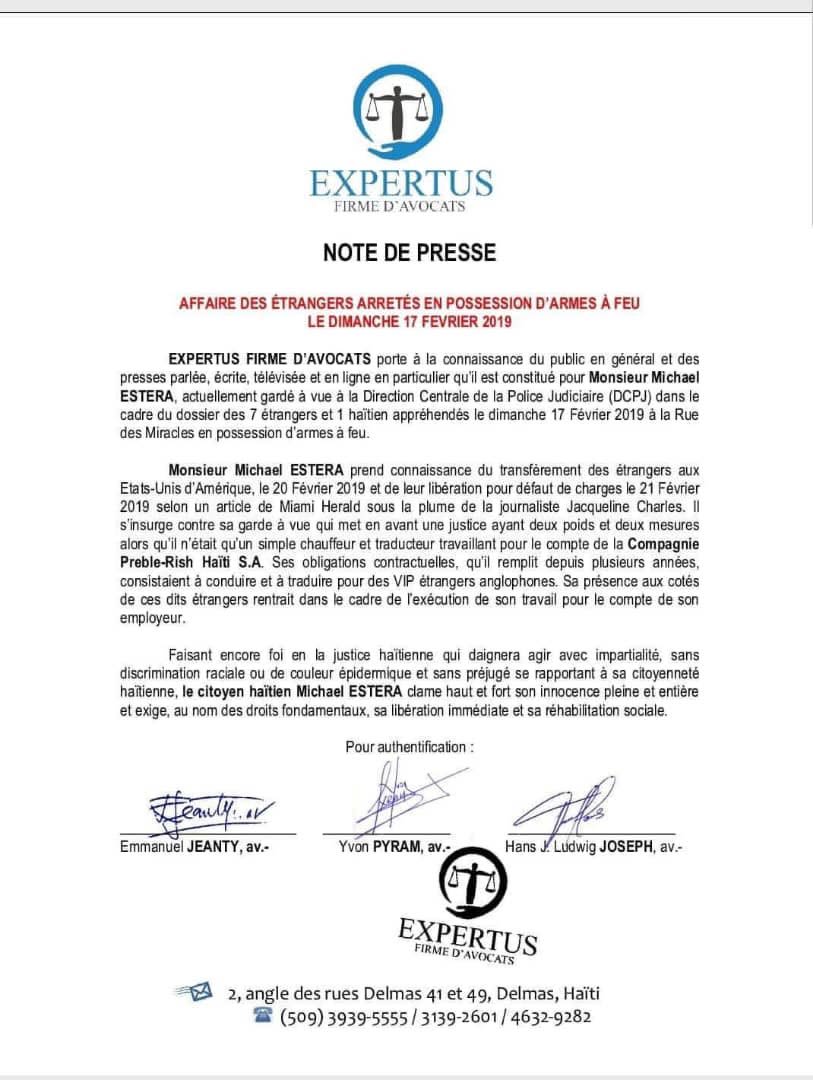

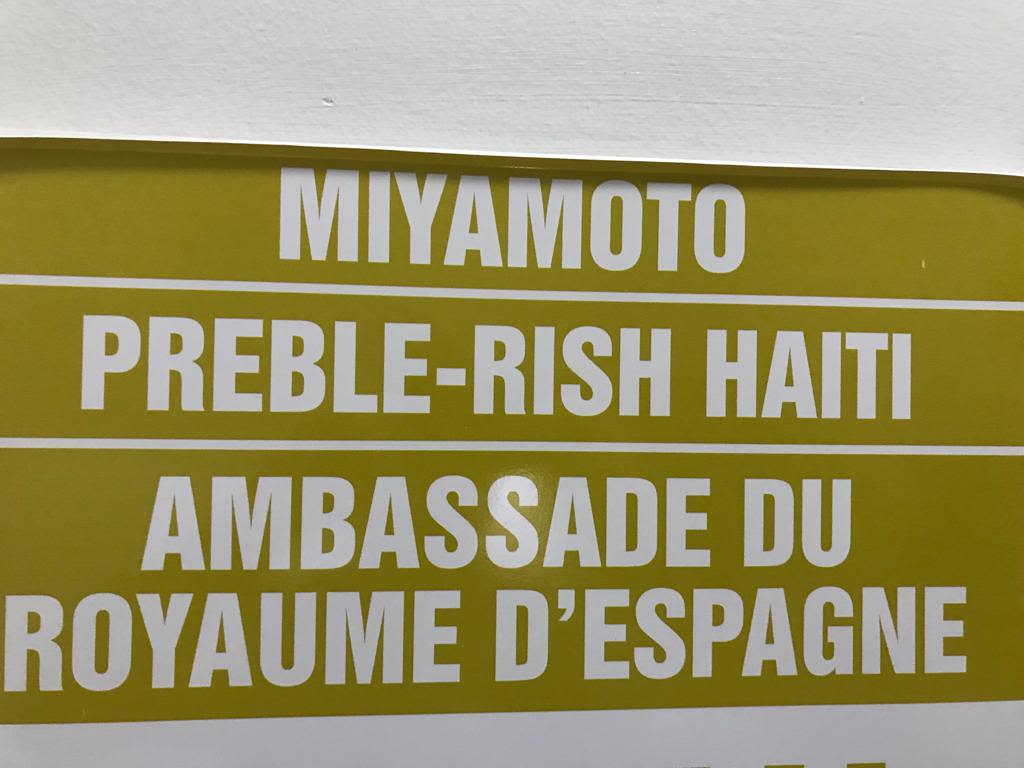

After seven of those detained were returned to the US, only Michael Estera, the Haitian national, remained in jail. When it was reported the Americans wouldn’t face charges, Hans Joseph, a lawyer representing Estera, released a statement, noting that Estera had worked for a local civil engineering company, Preble-Rish Haiti, and demanding his release.

Soon after, Preble-Rish Haiti deleted its “About Us” page from its website. An archived version, however, revealed two key names: Josue Leconte and Gesner Champagne. The latter was arrested in 1996 on arms trafficking charges in the United States. They were the same two local businessmen who allegedly met the plane from Baltimore at the airport the morning before the arrest.

I met with Hans Joseph, Estera’s lawyer, in a sparsely decorated office in the Delmas 41 neighborhood of Port-au-Prince. Joseph denied Preble-Rish had any role in hiring him, and claimed that Estera would not even disclose to his lawyers who specifically his boss was.

“His life is in danger,” Joseph told me with some urgency. Estera was just a driver and translator working for a local businessman, the lawyer told me. “One of the best around,” he added.

During their one night of freedom in Haiti, Estera dropped at least some of the contractors off at the Hôtel Montana, according to the lawyer. Estera has since been released from jail. He has remained silent. Who were these businessmen that Estera was working for?

THE “BUSINESSMEN” CLOSE TO THE GOVERNMENT

It remains unclear who, if anyone, signed a contract to bring this specific group into the country, but it is now evident that Preble-Rish Haiti, and the interests behind it, were intimately involved in the entire saga.

The company’s now-deleted “About Us” page showed that Leconte, an American citizen with a barely existent public record, was its president. The public relations director was listed as Champagne, whose “role involves creating relationships and support from both public and private institutions.”

It is a role that he is well-suited for given his relationship with former president Michel Martelly — and that appeared to have worked in the company’s favor.

Champagne is married to Claudia Saint-Remy, who is the sister of Martelly’s wife, Sophia Saint-Remy. Champagne's uncle was a top official in the Duvalier regime. He and Martelly have been close for decades.

In March 1996, Gesner Champagne was arrested in the United States on arms trafficking charges. Martelly, it was reported, paid the $150,000 bail, and Martelly owned the house at the Miami address Champagne listed in court documents. He eventually reached an accommodating plea deal after cooperating in another investigation. That agreement remains under seal.

Champagne was one of many friends and relatives who populated Martelly’s circle of influence following his 2011 ascension to the presidency. Another is Charles “Kiko” Saint-Remy, a brother-in-law of both Champagne and the former president who has been linked to a range of criminal actions including murder, kidnapping, and drug trafficking since Martelly’s presidency.

If the contract had an official stamp of approval, the involvement of Preble-Rish and Champagne, and their close connections to Kiko Saint-Remy and former president Martelly, raises significant legal and political questions.

What are the implications of an American citizen, Leconte, and an American-owned company, Preble-Rish, being at the center of this scandal? Why would someone convicted of arms trafficking, Champagne, be involved in official security operations? And to what extent was the current Haitian administration, or other government officials, aware of the operation?

What is clear is that it wasn’t just the two Preble-Rish businessmen who were involved with the contractors.

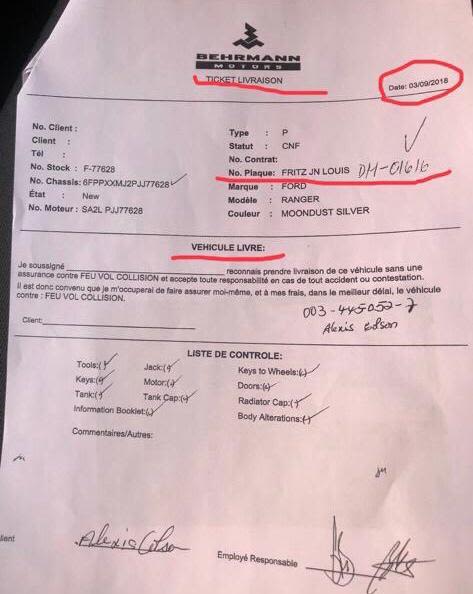

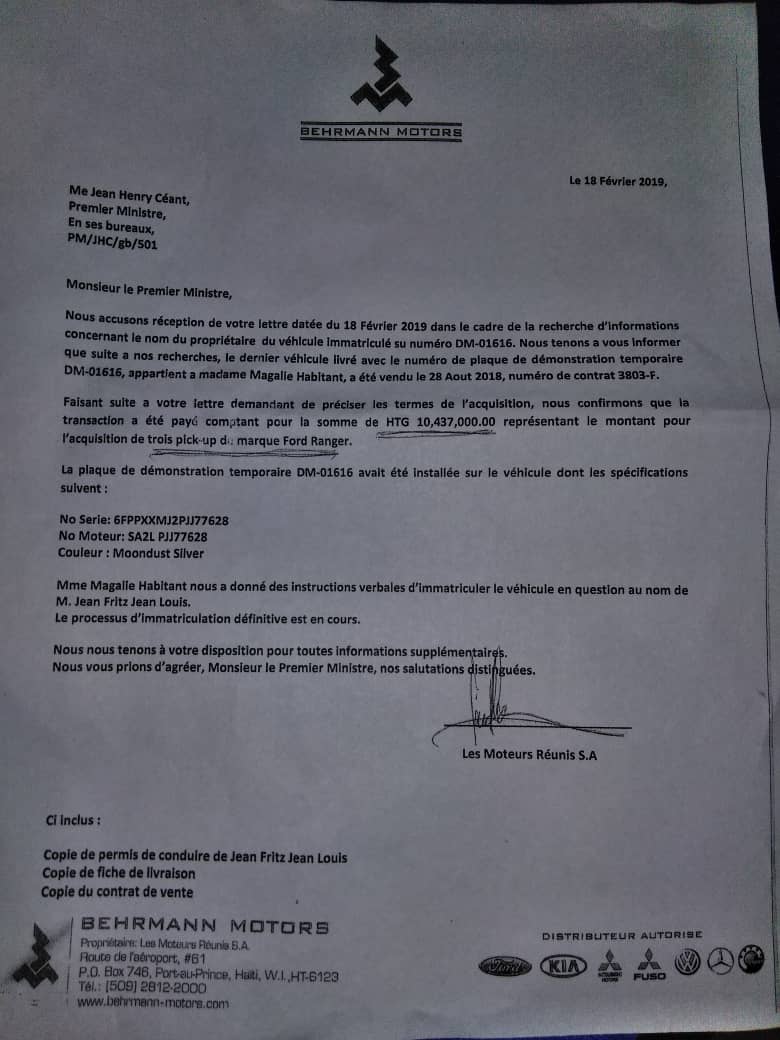

Police discovered three sets of license plates inside the vehicles when the arrest occurred. According to registration documents, and a letter from a local car dealership addressed to the prime minister, one of the plates was registered in the name of Fritz Jean-Louis, reportedly an advisor to the current president, and a former secretary of state for the interior. Jean-Louis was also a minister involved with electoral affairs in 2015, during President Moïse’s campaign.

The letter explains that Magalie Habitant, at the time the director general of the public waste management authority, purchased a moondust Ford Ranger, and two other pickups, in Jean-Louis’ name in late August 2018.

Another set of plates, and a dark green Toyota Helux, is registered to Preble-Rish Haiti. Officially, the company had been the owner for less than four weeks. On January 22, 2019, Estera, the Preble-Rish driver, signed paperwork transferring the deed from Steeve Khawly, a wealthy importer who ran for president in the last election for a pro-government party.

Contacted by Ayibopost, Khawly said he had purchased the car in 2013 “at the request of a friend from the company Preble-Rish.” Khawly and Champagne are both listed as founders of the Seguin Foundation in Haiti. Champagne did not provide any explanation of his involvement when contacted by Ayibopost. “Ask the state authorities who released the soldiers what happened," he told the outlet. “Ask the American officials why they released these gentlemen.”

As of yet, the owner of the third set of plates is unknown.

If the current administration was aware of the contractors’ presence, they’ve tried to distance themselves from the fallout. “The president is not involved in this matter,” a lawyer for Moïse said, denying any official relationship with Fritz Jean-Louis. “The executive power cannot engage mercenaries to terrorize the population,” a spokesperson said. At that point, Jean-Louis had fled the country, according to police.

But the timeline of events preceding the arrest, and new information obtained about who was involved in the case, indicates the network of individuals who planned and coordinated the arrival of the security contractors was likely far broader than just Leconte, Champagne, and Jean-Louis.

WASHINGTON, DC

Since the return of the detained contractors, the US government has made no public remarks about the case. On Friday, February 22, the State Department held an informal telephone briefing for members of Congress and staff interested in the case. In response to questions about details concerning the Americans or what the group was doing in Haiti, the official on the call apparently provided no specifics. But those questions are unlikely to stop.

On February 6, Haitian foreign minister Bocchit Edmond tweeted a picture after meeting with US Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL), who has become a “shadow secretary of state” for the Western Hemisphere under the Trump administration. The next day marked the two-year anniversary of Jovenel Moïse’s inauguration as president, and was the beginning of the street actions that would lock the country down for the next 10 days.

On February 9, a delegation from Haiti’s central bank and ministry of finance arrived in Washington, DC. Foreign Minister Bocchit Edmond was also in DC, and accompanying him were two individuals: Charles Jean-Jacques, a government official in charge of foreign development funds, and the wealthy businessman and government supporter, Andy Apaid.

The Miami Herald reported that Bocchit Edmond had held discussions concerning a debt-financing deal, where Qatar would buy Haiti’s Petrocaribe debt to Venezuela. According to sources with knowledge of the situation, Apaid, the Central Bank governor, and the finance minister also discussed the Qatar deal while in Washington. That debt is at the center of anticorruption protests that have rocked the country for the last five months.

The relationship between the Haitian and US government shifted in January, when Haiti broke with years of government policy and voted in favor of a resolution at the Organization of American States (OAS) declaring the government of Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela illegitimate. Overthrowing the Maduro government has become priority number one for the White House and Senator Rubio.

With Moïse's mandate under threat, the president switched positions and voted with the US. The decision was met with outrage, both in Haiti, and among other Caribbean leaders.

“Poor Haiti. They can’t withstand the pressure,” Ralph Gonsalves, the prime minister of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, told the Miami Herald after Haiti bucked the majority of its Caribbean allies and recognized Juan Guaidó as interim president of Venezuela. “The current president of Haiti is just craving for US protection. That’s all. This guy came to the presidency entirely unprepared,” Gonsalves added.

But it is clear the Haitian government is seeking to turn the goodwill generated from its OAS vote into US support in its own political crisis. The delegations in DC also discussed an IMF rescue package (officially announced March 7) and met with US rice producers in an ill-fated effort to lower prices in Haiti.

That the financing deal with Qatar is gaining at least some traction now, it appears, is closely linked with Haiti’s OAS vote. There was concern in Haiti that, after switching its vote, the Venezuelan government would demand repayment. Haiti would be unable to do so — causing more financial problems for the government. On February 12, the Central Bank president and finance minister arrived back in Haiti, where the crisis showed no signs of abating.

On February 14, President Moïse broke a week of silence and addressed the nation concerning demands for his resignation and generalized unrest that had already led to multiple deaths and ground the country’s economy to a halt. He categorically refused to step down. "I will not leave the country in the hands of armed gangs and drug traffickers,” he declared in a prerecorded message.

In a comment that many are now reading more into, Moïse thanked the international community for the “great support they give us, especially in the security field, which they continue to provide.”

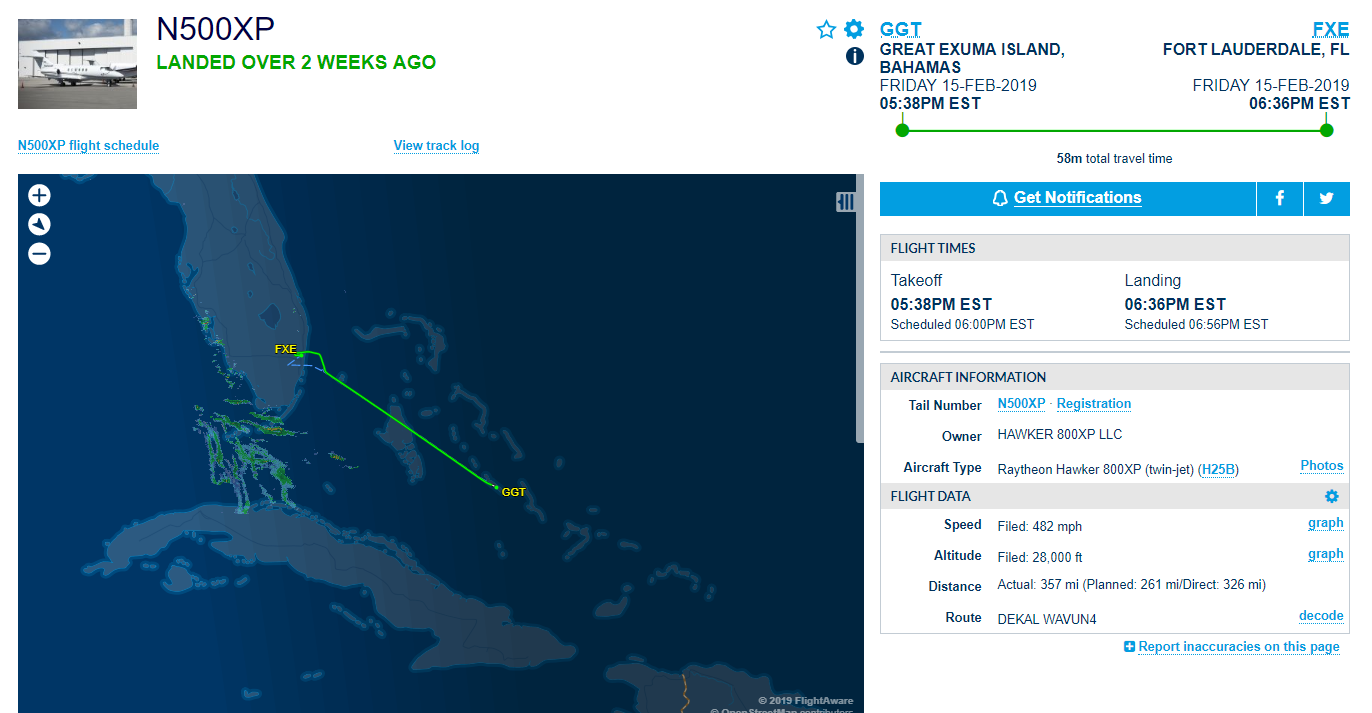

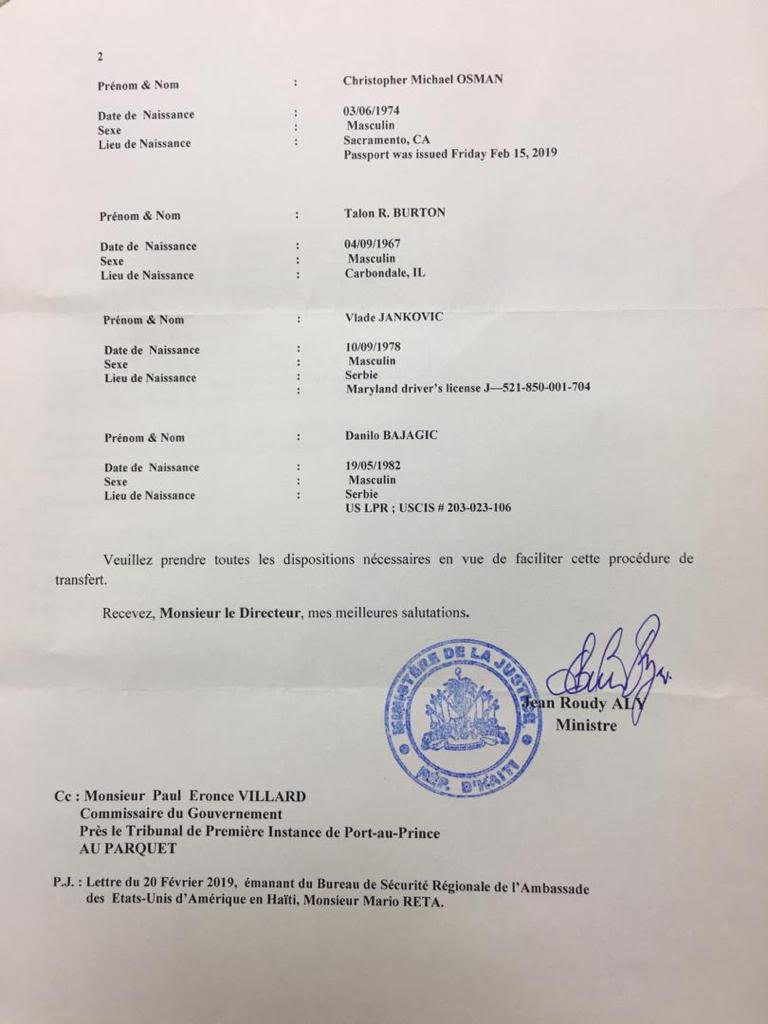

The next day, at the White House, Foreign Minister Bocchit Edmond met with Trump’s national security advisor John Bolton. The same day, a passport was issued to Christopher Osman, one of the detained contractors, according to a Haitian Ministry of Justice document, and a private jet departed the Bahamas en route to Baltimore.

Haitian Ministry of Justice document regarding the passport issued to Christopher Osman, one of the detained contractors.

The Miami Herald reported that Haiti’s government had previously requested reinforcements from the United Nations, which has had police and soldiers on the ground for 15 years, but were rebuffed. Could the Haitian government have requested security assistance while in Washington as well?

I reached out to Apaid, the businessman who had traveled to Washington, asking if he would be willing to talk about the security contractors situation. He declined.

As of today, it remains unclear if these security contractors’ presence in Haiti is in any way related to the government’s trips to Washington, or if any US government officials had advance knowledge of, or provided any support for, the contractors’ work in Haiti. But, by facilitating the contractors’ release, the US saved the Haitian government from further embarrassment.

Based on interviews and records obtained as part of this investigation, it is the connection to this case of another member of the Haiti delegation that is most sure to raise new questions about the nature of, and official involvement in, this operation.

Haitian foreign minister Bocchit Edmond with US Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL).

Haitian foreign minister Bocchit Edmond with US Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL).

Bocchit Edmond also met with Trump’s national security advisor John Bolton.

Bocchit Edmond also met with Trump’s national security advisor John Bolton.

THE CENTRAL BANK

Rumors filled the days that followed the contractors’ arrest in Haiti. Opposition leaders accused the government of bringing foreign mercenaries into the country to target political opponents and protesters, dozens of who have been killed in the last six months. The prime minister implied they were in the country to assassinate him, no doubt complicating the situation politically and diplomatically. But many explanations centered around the Central Bank.

Fritz Jean-Louis, the former government official involved with the case, suggested to police that the contractors were there to provide a security assessment as part of a contract with the Central Bank. But Jean Baden Dubois, the bank’s governor, and other government officials quickly denied any link. Though the bank has hired foreign experts to assess the bank’s security in the past, they would not be heavily armed, or trying to enter the bank on a Sunday afternoon, multiple sources close to the bank explained.

On February 19, two days after the detention, a government lawyer, Reynold Georges, spoke to the press and provided yet another theory. Georges called the contractors “professional thieves” who had attempted to rob the Central Bank. He later thanked the “vigilance” of a bank security guard who tipped off the police and thwarted their planned heist.

Outspoken opposition leader Moïse Jean Charles charged that the contractors were at the bank not to rob its vaults, but to destroy damaging records about government corruption related to billions in Petrocaribe spending.

It remains unclear precisely what the contractors’ mission was. But, based on numerous interviews, records obtained as part of this investigation, and on other sources, the chain of events on Sunday, February 17 that led to the contractors’ arrest a few blocks from the Central Bank have become clearer — and indicate central bank awareness at the highest level.

That morning, Estera picked up at least some of the contractors at the Hôtel Montana, according to his lawyer. Later, three vehicles matching the descriptions of those used by the contractors were photographed pulling into the private residence of Gesner Champagne, the Preble-Rish employee and close friend of former president Michel Martelly.

Around 2 p.m., at least some of the contractors arrived at the parking garage of the Central Bank in downtown Port-au-Prince. According to multiple sources close to the bank, the security guard on duty refused them entry.

The guard, whose identity HRRW is withholding due to security concerns, contacted multiple bank officials, who then contacted the governor of the Central Bank, Jean Baden Dubois, according to source with knowledge of the situation. One individual involved in the bank officials’ conversations throughout the day was Rosemond Pierre, the head of the bank’s information technology department, those same sources indicated. At one point he even called the guard directly. Pierre declined to comment for this report.

It appears the guard continued to refuse entry to the contractors. Though initial reports said the contractors were detained at a police checkpoint, the most likely explanation is that someone at the bank tipped off police.

The evening the contractors were detained, Baden denied the bank played any role in what happened. However, according to a source close to the local police investigation, when officials initially contacted Baden on the night of February 17, he acknowledged the bank had played a role and allegedly claimed he was under pressure. What role exactly, and under pressure from whom, remains unclear.

Many of those consulted noted that Baden’s term as central bank governor ends in July. He was promoted from director general by Martelly in 2015, and is believed to be seeking another term. The Central Bank, however, has faced criticism over its handling of the economic crisis. Inflation is in the double digits, and the currency has lost half its value against the dollar since Baden’s term began.

What has become clear, according to sources with knowledge of the situation, is that the Central Bank governor had been in touch with Josue Leconte and Fritz Jean-Louis, two of the individuals at the center of this scandal, since early February. It is not known if the discussions were related to the contractor situation. Baden declined to comment.

Was the Central Bank itself part of the operation, or just the site of its downfall? In early March, Baden told a local journalist that bank security cameras confirmed there had been no break in at the bank. He declined to offer further details. But the available information indicates that the Central Bank governor could shed significant light on what really happened on Sunday, February 17.

Moreover, the involvement of officials involved in the bank’s information technology department raises significant questions about what the purpose of the visit to the bank really was, and what, if any, relation the operation had to the discussions held in Washington weeks earlier.

THE “RESCUE” AND THE POLITICAL FALLOUT

Soon after the contractors’ detention on February 17, a local journalist started filming live on Facebook, broadcasting images of the group, all men, inside a local police station called the “Cafeteria.” The reporter witnessed the minister of communications enter the police station, followed by the government prosecutor. Images of passports, and of the cache of equipment that the police had discovered, spread over social media.

A local journalist for RSF began filming live on Facebook from the police station where the contractors were detained.

That evening, Haitian government officials tried to intervene and secure the group’s release. One of President Moïse’s advisors made a call. And that evening, the minister of justice personally intervened, according to reports in the local press, independently confirmed.

Police and judicial officials resisted for days, promising thorough investigations and professionalism. It was clear that the presence of armed foreigners, and the possibility they were working for the government, caused resentment among certain police officers and officials. The politicization of Haiti’s security forces remains a significant concern, including among international partners who have contributed hundreds of millions of dollars to professionalization efforts.

From the beginning, the case itself was political. And regardless of what the contractors were doing, or whom exactly they were working for, their detention exposed the depths of the current political crisis in Haiti — and their “rescue” by the United States helped to put a lid back on top of it.

For days, however, there was no indication the United States would get involved. In a brief statement on February 19, the embassy noted that it had provided normal consular services to the detained Americans. “Due to privacy considerations, we are unable to comment further,” the statement concluded.

That afternoon, in an impromptu interview with CNN at his residence, Prime Minister Jean-Henry Céant referred to those detained, who had yet to be formally charged, as “terrorists” and “mercenaries.” He then implied that they wanted access to the roof of the Central Bank in order to assassinate government officials, in particular Céant himself.

If Moïse was pushed to resign as president, it would likely be Prime Minister Céant, who ran as an opposition candidate in the previous election, next in line. The power struggle coloring the background of the ongoing political crisis was on full display. US embassy officials were incensed, and that evening the prime minister’s staff desperately tried to control the situation.

On February 20, the minister of justice sent a letter requesting the release, into US custody, of the seven US-based contractors. Attached, though not made public, was a letter from Mario Reta, the embassy’s regional security officer, apparently requesting the transfer. When Americans are arrested for violating local laws, they must face local charges, and the State Department makes clear it cannot “get U.S. citizens out of jail.” And this was not a formal extradition.

Letter requesting the release, into US custody, of the seven US residents from the minister of justice.

Letter requesting the release, into US custody, of the seven US residents from the minister of justice.

The minister’s letter claimed that the group would face arms trafficking charges upon their return to the United States. Unknown to those of us following the story on the ground (we were at court that afternoon, waiting for the detained contractors’ first appearance before a judge), the Americans were already at the airport.

When they arrived in Miami, US law enforcement reportedly met them on the plane. What agency was responsible for this, however, remains a mystery. Local police departments, the Department of Justice, FBI, TSA, and the US Marshals Service all denied any involvement, according to Task & Purpose. Two agencies that have yet to make any public statements are the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives; and the Drug Enforcement Administration.

The following day, citing “federal sources,” the Miami Herald reported that “the men will not be charged criminally, but are being debriefed.” The contractors, the Herald continued, “told US authorities they were on the island providing private security for a ‘businessman’ doing work with the Haitian government.” The Haitian president and prime minister both denied having any knowledge of their departure.

Though the United States had told Haitian judicial authorities that the men would face arms trafficking charges once they returned to the US, multiple sources close to the case, including in law enforcement, said they believe that the guns themselves were already in Haiti. A Haitian Senator charged that Leconte, the Preble-Rish businessman, provided the weapons. Haitian police are currently holding the equipment.

It’s unclear if the United States ever intended to bring charges, or if it just provided a justification for their release to US custody, but it remains possible that the US contractors, while violating many Haitian laws, did nothing wrong in the eyes of the US justice system. If the guns were already in the country however, they most likely were brought in illegally, and the contractors could have knowledge of how they were obtained, and by whom.

At noon on February 22, Lance Burton, the CEO of Hawkstorm Global, and brother of one of the detained Americans, told me over email: “We are bouncing our statement off the key players involved to make sure everyone is good to go with the release.” About two hours later, Christopher Osman posted his message on Instagram. I haven’t heard from Burton since. Osman wrote:

We were not released we were in fact rescued. To the men who risked their lives to do so: you boys are getting some serious care packages!!! We owe you our lives. ... It’s been a long time since I have seen the weight of the US government at work and it’s a glorious thing.

Osman quickly switched his account to “private,” but not before international media picked up his statement. The account is public again, but the post appears to have deleted.

In Haiti, the decision to release the contractors caused outrage, with many commentators pointing to the fact that the United States has provided financial support to, and touted the successes of, the Haitian justice system for years. If they believed in the institutions, why did the embassy prevent the contractors from facing a judge? The decision is “ugly, worse than a slap in the face,” one prominent radio personality opined, the Herald reported.

“The fact that the U.S. took these people and did not charge them, it shows there was a conspiracy,” Pierre Esperance, the executive director of the National Human Rights Defense Network in Haiti, told the Miami Herald. “They didn’t want them to go before Haitian justice,” he added. It now appears the local investigation has stalled.

But the question remains: why did the US break diplomatic protocol and intervene? Was it to protect US citizens from a politicized trial? To protect the Haitian government from its domestic opponents? To put a lid on a story that was peeling back the earth, and exposing the fault lines threatening the Haitian president’s mandate? Or was it something more?

This investigation has provided significant new details about the case, but many questions remain unanswered. When I was in Haiti the week after the detention, many contacts noted the perception of fear resulting from the case and the automatic weapons found in the contractors possession. In November, images had surfaced of apparent foreigners embedded within the president’s palace guard. Political leaders and other actors have alleged that there are additional contractors still in Haiti, positioned in various cities and even near the residence of President Moïse. In the absence of a public investigation and clear explanation, that fear will remain, as will persistent allegations of the contractors’ involvement in the deaths of protesters.

One thing remains clear: we have yet to hear the end of this story.

A local journalist for RSF began filming live on Facebook from the police station where the contractors were detained.

A local journalist for RSF began filming live on Facebook from the police station where the contractors were detained.

Some of the cache of equipment that the police discovered.

Some of the cache of equipment that the police discovered.

Some of the cache of equipment that the police discovered.

Some of the cache of equipment that the police discovered.

Some of the cache of equipment that the police discovered.

Some of the cache of equipment that the police discovered.

If you appreciated this work, please consider a donation to support the Center for Economic and Policy Research.

APPENDIX

Learn more about the investigation

Key Findings

- At least one of the contractors was previously in Haiti, having been brought in by a prominent elite family after fuel price protests in July of 2018.

- At least some of the contractors arrived in Haiti at 5 a.m. February 16 on a privately chartered plane that departed Baltimore. Their passports were not stamped by Haitian immigration.

- Those who arrived on the plane were met at the airport by two local businessmen affiliated with the company Preble-Rish Haiti S.A. and a former government official who is reportedly an advisor to the president.

- Two of the vehicles the contractors were in when police detained them were registered to Preble-Rish and the former government official, respectively. The owner of the third vehicle is unknown.

- Preble-Rish is an American-owned company whose public relations director is Gesner Champagne. Champagne, the nephew of an influential Duvalier regime official, is childhood friends with former president Michel Martelly. Champagne was arrested in 1996 in the United States on arms trafficking charges.

- Less than a week prior to the contractors’ detention in Haiti, two Haitian government delegations were in Washington, DC looking for support from the US government amid the ongoing crisis. The Haitian government has sought to capitalize on its recent vote against Venezuela in the OAS.

- Discussions in Washington, DC, which involved an influential private sector businessman, centered around a deal wherein Qatar would buy up Haiti’s Petrocaribe debt to Venezuela.

- On Sunday, February 17, before the contractors were detained, at least some of them tried to enter the Banque Republique d’Haiti, the nation’s central bank. They were rebuffed.

- The governor of the Central Bank, who has denied any bank involvement, had been in touch with one of the Preble-Rish businessmen for at least two weeks before the contractors’ arrival in Haiti.

- When the contractors attempted to enter the Central Bank, key bank officials were made aware of the situation. Officials from the bank’s information technology department were involved in those discussions.

- After the contractors’ detention, Haitian government officials, including the minister of justice, attempted to intervene and have them released.

- The detention of the contractors exposed a political rift between the Haitian president and prime minister, and the case became enmeshed in the ongoing political crisis.

- After three days in jail, the US embassy intervened and secured the contractors’ release, quietly escorting them to the airport and flying them to Miami where they were met by US law enforcement. The US government told Haitian authorities the men would be charged with arms trafficking.

- The weapons seized with the contractors are believed to have been in Haiti at the time of the their arrival. And the contractors will reportedly face no charges.

- The State Department has yet to provide details, even to some members of Congress.

- In Haiti, the result of the contractors’ detention is fear among the population; political leaders have alleged additional security contractors are in the country.

Witness List

- Jovenel Moïse: The current president of Haiti, Moïse was the handpicked successor to Michel Martelly. He is the owner of a banana plantation in northern Haiti that has received millions in state funds. He took office on February 7, 2017.

- Michel Martelly: The former president took office in April 2011 after the US intervened in the presidential election and secured him a spot in the runoff. A musician with ties to Duvalier-era military officials, Martelly remains an influential player in Haiti’s current politics, and the expectation is that he will run for president in the next election.

- Jean-Henry Céant: The current prime minister of Haiti, Céant was named to the position as part of a political compromise between the president and some of his political opponents in August 2018. Céant, who ran for president in the last election, would be next in line if Moïse left office. He accused the contractors of being “terrorists” who had come to Haiti to assassinate high-level officials, including Céant himself.

- Josue Leconte: An American citizen, Leconte formed Preble-Rish Haiti S.A. in 2011. Leconte was allegedly present at the airport when at least some of the contractors arrived on a private plane. In 2010, he appeared in the credits of a PBS Frontline documentary with Sophia Saint-Remy (Martelly’s wife).

- Gesner Champagne: The nephew of a Duvalier-era general, Champagne was arrested in 1996 in the US on arms trafficking charges. Former Haitian president, and founder of the current ruling party, Michel Martelly paid his bail. Champagne is married to Claudia Saint-Remy, the sister of Martelly’s wife, Sophia. He is the public relations director for Preble-Rish Haiti S.A., and was allegedly with Leconte at the airport to pick up the contractors.

- Charles “Kiko” Saint-Remy: Brother-in-law of both Champagne and Martelly, “Kiko” has been linked to a range of criminal activities including kidnapping and drug trafficking.

- Fritz Jean-Louis: A former secretary of state for the interior under Martelly, and a minister in charge of electoral affairs during current president Jovenel Moise’s campaign, Jean-Louis was among the group who allegedly met the contractors at the airport. Police believe that Jean-Louis has since fled the country.

- Chris Handal: A member of a prominent elite Haitian family, this past July Handal brought at least one of the detained contractors to Haiti following days of protests which appeared to target businesses, including those partially owned by Handal.

- Andy Apaid: Another prominent member of the Haitian elite, Apaid led the Group of 184, a US-backed coalition of “civil society” that helped overthrow Jean Bertrand Aristide in 2004. He was a part of a Haitian government delegation that traveled to Washington, DC in February.

- Jean Baden Dubois: Martelly appointed Baden, the governor of the Central Bank, to his position in 2014. His term is up this summer. Baden had been in contact with Leconte and Jean-Louis for weeks preceding the contractors’ detention in Haiti. He denied any knowledge of the situation the night of the detention.

- Pierre Rosemond: The head of the Central Bank’s information technology branch, Rosemond was active in discussions throughout the day of the detention with high-level bank officials, according to sources with knowledge of the situation. At one point Rosemond called the security guard who had denied access to the contractors, according to those same sources.

- Bocchit Edmond: Haiti’s foreign minister, Edmond has attempted to cultivate better ties with Washington since Haiti’s decision to break years of precedence and join the US at the Organization of American States in voting to not recognize Nicolás Maduro’s legitimacy in Venezuela. In the weeks prior to the detention, Edmond met with Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL) and President Trump’s national security advisor John Bolton.

- Marco Rubio: A conservative senator from Florida, Rubio has become the Trump administration’s de facto secretary of state for the Western Hemisphere. A leading proponent of regime change in Venezuela, Rubio met with Foreign Minister Bocchit Edmond in early February.

- John Bolton: Trumps’ national security advisor, Bolton has recently declared the Monroe Doctrine alive and well in the Western Hemisphere. A former State Department official and US ambassador to the United Nations under the Bush administration, Bolton faced questioning as part of his confirmation hearing about a potentially improper shipment of thousands of weapons to Haiti in 2004.

- Michele Sison: The current US ambassador to Haiti, Sison holds the State Department’s highest diplomatic rank as Career Ambassador. Osman, the one contractor who has made any public remarks, specifically thanked the ambassador for his “rescue.” Sison has been ambassador to Lebanon, the United Arab Emirates, Sri Lanka and Maldives as well as holding diplomatic posts in Iraq, Pakistan, India and elsewhere.

- Mario Reta: The US Embassy’s regional security officer, Reta sent the letter to the Haitian ministry of justice requesting the release into US custody of the detained contractors.

The Detained Contractors

One of the remaining mysteries surrounding the detained contractors is: who hired them? Certainly, the majority of those detained have backgrounds that are consistent with private security work, but the fact that they all appear to work for different companies has raised concern about what entity actually brought them all together.

Who are they?

Kent Kroeker, a former marine pilot, is the chief operating officer of California-based Kroeker Partners. The company is run by Kent’s father, Mark, who was a former UN police advisor. In the mid-'90s, and again in the mid-2000s, Mark Kroeker was involved in international efforts to reform Haiti’s security services. After his son’s detention, the firm posted a brief statement to its website stating that it did not have “any active engagements” in Haiti.

Danilo Bajagic, a Serbian national and US green card holder, is employed by K17, a security services company based in Rockville, MD. “This [was] not a K17 operation,” a company spokesperson told Paul Szoldra of Task & Purpose. “We do not do international work such as this.” Bajagic has worked for K17 for eight years, according to his LinkedIn profile, which has been removed since his return to the US. Jankovic, the other Serbian national, has yet to be publicly linked to any of the companies involved, but it is rumored that he also works for K17. Public records indicate he lives in Germantown, Maryland, where Bajagic lives.

Talon Burton is a former Blackwater contractor and now works with his brother Lance Burton, the CEO of a Dallas-based security service firm, Hawkstorm Global. According to Talon’s LinkedIn profile, he also previously worked as a diplomatic security officer, and was “the Agent in Charge of the protection detail for both United States Ambassadors to Afghanistan Karl Eikenberry and Ryan Crocker.” Lance Burton repeatedly told me the company would release a public statement and would even be happy to sit down for an interview. They have not done either.

Dustin Porte, the only one of the detained apparently without a history in military or private security, incorporated an electrical services company, Patriot Services, in Mandeville, Louisiana in 2014. Porte is the son-in-law of former Mandeville mayor, Eddie Price, who was convicted on federal income tax evasion and corruption charges in 2010. According to news reports from the time, Porte participated in relief efforts in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake as part of the Louisiana National Guard.

One of the former SEALs, Christopher Mark McKinley, is the founder of INVICTVS Group, which describes itself as a “consortium of US special operations veterans” providing security, consulting, training, and other services. McKinley, however, used to go by the name Christopher Heben. Over a decade in the SEALs, Heben served as a “medic, sniper, an intelligence analyst and more,” according to a report in the Ohio press, where Heben grew up.

After leaving the military, Heben became a physician’s assistant before having his medical license revoked in 2008 when he was found guilty on three counts of felony forgery charges. He was back in the news in 2014, after he claimed he had been shot in the stomach over a parking lot dispute. It turned out not to have happened, but Heben was eventually found not guilty of falsifying a police report. In recent years, McKinley emerged as one of the media’s favorite on-air special operations experts, and has regularly appeared on Fox News and other outlets. Last year, his medical license was reinstated.

The only contractor to have made any public statement upon returning to the United States is Christopher Osman. Another former navy SEAL, Osman “was one of the first elite commandos to fight in Afghanistan following the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks,” according to a 2017 report in the San Diego Union-Tribune.

Like McKinley, Osman has had his own problems with the law. In August 2017, he was arrested on felony assault and battery charges stemming from a road rage incident. He eventually pleaded guilty to a lesser misdemeanor assault charge. Today, Osman owns and operates Chris Osman Designs, which sells military grade motorcycle accessories. Osman did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

An American-Owned Company with a History of Haitian Government Contracts

Much of this was first reported in French by Patricia Camilien of La Loi de Ma Bouche.

Less than three months after Michel Martelly took office in 2011, two Americans, Ralph Rish and Josue Leconte, opened a bank account and met to establish a civil engineering company called Preble-Rish Haiti S.A.

The company itself is 99 percent American-owned, according to its local incorporation documents. Rish and his partners — Christopher Brian Forehand, Alan Philip Jones, and Clifford Lawrence Knauer — held 70 percent of the shares. Leconte held 29 percent, and Ralph (Kaleb) Leconte, the only Haitian national, held 1 percent. As Camilien notes, legally, a Haitian company must have at least one Haitian national board member.

All of the shareholders except Forehand and Ralph (Kaleb) Leconte also are on 2013 Florida incorporation records for PRI Haiti-USA, Inc. The company is no longer active.

Rish, Forehand, Jones, and Knauer have all been employed at Preble-Rish Inc., the firm that Ralph Rish founded in the early ‘90s. All are listed, along with Preble-Rish Inc., in a federal foreclosure case that was resolved in late 2013. Rish resolved a multiyear personal bankruptcy case in 2016. Around the same time, the company was absorbed by Dewberry.

Whether the group retains its stake in Preble-Rish Haiti is unknown. In 2016, Rish registered a new Florida company, this one a bar and restaurant called the Haughty Heron. Contacted on a number associated with the bar, Rish provided a curt response when asked if he had any relation to the company in Haiti. “No, sir,” he said, and hung up.

The company in Haiti appears to have had some success, however. According to research published by Camilien, the company received its first government contract in December 2012. It didn’t get its official operating license for another 120 days, when it formalized its paperwork with the minister of finance.

Its website describes the company as doing business with a variety of government and international clients, including the Inter-American Development Bank; DINEPA, the Haitian water authority; and the Ministry of Public Works. Some projects were “financed through the Petro Caribe Fund and other international donors,” the company’s website note

The Haitian government’s use of Petrocaribe resources, some $2 billion in low-interest loans provided by the Venezuelan government since 2008, has been at the center of a corruption scandal that has been growing for more than a year, and which has implicated government officials at the highest level, including the president himself.

Today, Preble-Rish Haiti’s office sits on the fifth floor of the Hexagone building in Petionville, also home to diplomatic missions from Brazil and the Organization of American States.

But their government contracts haven’t always gone so smoothly. On February 27, the director of DINEPA, Guito Edouard, went on Radio Vision 2000, a local station, and alleged that Leconte and Champagne — the two Preble-Rish employees apparently at the center of this alleged security operation — had threatened his life. The two allegedly were requesting some $313,000 in compensation for work the DINEPA director claimed was never completed.

In March, Camilien noted that Preble-Rish also had a Spanish-based entity, also owned by Leconte.

Adding another twist, one of the lawyers who signed the company’s paperwork was Sylvie Handal Roy, the wife of the businessman who had brought one of the detained contractors to Haiti in July.

The Plane

One of the first details to emerge following the contractors’ arrest was that none of them had received stamps from Haitian immigration upon their entrance to the country. Even if the contractors were on an official security mission, the lack of stamps raised a number of questions, including how they managed to get into the country in the first place.

HRRW is now able to confirm that at least some of the contractors arrived at Port-au-Prince international airport on Saturday, February 16 aboard a privately chartered plane.

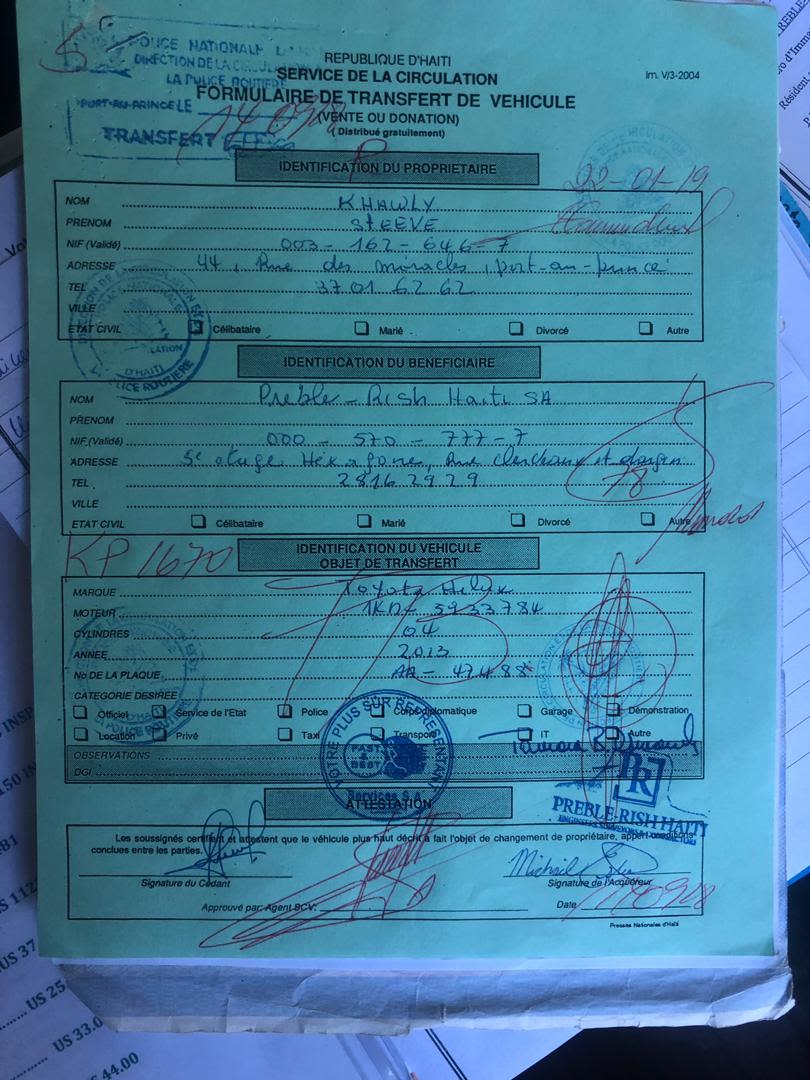

The plane, with tale number 500XP, and registered to HAWKER 800XP LLC in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, departed Maryland’s Baltimore/Washington International Airport under the cover of night at 2:06 a.m. The plane arrived in Haiti at 4:59 a.m., well before the airport was officially open.

In July 2017, Augusto Lewkowicz incorporated the company, HAWKER 800XP LLC, according to Florida business registration records. Lewkowicz, who also goes by Daniel, is the president of ExecuFlight, a private charter company based in South Florida. Charter companies generally lease plans from various owners, but in this case, ExecuFlight appears to be leasing the plane from Lewkowicz himself.

“The flight was not clandestine,” Lewkowicz, reached by telephone, explained. There was a proper passenger list, and the company had received all the necessary paperwork for the flight from Baltimore to Haiti, he said. Flight records show it was the only trip the plane made to Haiti in the last three months. Citing privacy concerns, Lewkowicz would not comment on any client information.

Though it is unclear who contracted ExecuFlight’s services, flight activity before and after the visit to Haiti indicates that Port-au-Prince was not its only destination.

On February 14, the plane departed Fort Lauderdale, traveling to Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport in Puerto Rico before reaching its destination at Exuma International Airport in the Bahamas around 3 p.m.

The next day, the flight departed at 5:38 p.m. en route back to Fort Lauderdale. Three hours after arriving back in Florida, the plane was in the air, and touched down in Wilmington, NC at 11 p.m. It quickly departed again, reaching Baltimore’s BWI airport just before 1 a.m. That is where the direct flight to Port-au-Prince originated, departing BWI just after 2 a.m. early the morning of February 16.

After dropping off at least some of its passengers in Haiti, the plane continued along a similar path, flying to the Bahamas for a 24-hour stopover. Lewkowicz explained that the plane was in the Bahamas for a different reason, and was simply returning to where it originated.

On February 17, the plane took off once again, stopping in Puerto Rico before returning to Fort Lauderdale. The plane was back in Florida by the time police detained the contractors.

It’s not the first time the charter company has been in the news.

On November 10, 2015, an ExecuFlight jet crashed into an apartment building in Akron, Ohio. All nine individuals aboard, including both pilots, died. After its investigation into the crash, the National Transportation Safety Board found evidence that corporate wrongdoing and safety violations contributed to the crash. The company is currently engaged in an ongoing wrongful death lawsuit in Southern Florida, court records show.

Jake Johnston is a Research Associate at Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, DC. He graduated from Boston University in 2008 with a B.A. in Economics. At CEPR, his research has focused predominantly on economic policy in Latin America, the International Monetary Fund and US foreign policy. He is the lead author for CEPR’s Haiti: Relief and Reconstruction Watch blog and has authored papers on Haiti concerning the ongoing cholera epidemic, aid accountability and transparency and the US foreign aid system. His articles and op-eds have been published in outlets such as The New York Times, The Intercept, NACLA, Boston Review, VICE News, Al Jazeera America, and Truthout.